Opinions

12:36, 25-Dec-2017

Opinion: Will latest UN sanctions bring about a peaceful solution to the Korean nuclear issue?

Guest commentary by Liu Youfa

As 2017 nears its end, the prospect of the Korean nuclear issue remains as grey as ever, despite the United Nations’ recent adoption of Resolution 2397, which imposes ever tighter sanctions against the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK).

The Security Council voted unanimously on Dec. 22 to approve new sanctions on the DPRK, in response to the latter’s launch of a Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile on Nov. 28. The resolution condemned the launch and further tightened sanctions on the country, restricting its fuel imports as well as DPRK citizens working abroad.

Members are seen voting at a United Nations Security Council meeting concerning new sanctions on the Democratic People's Republic of Korea at UN Headquarters in New York, US, December 22, 2017. /VCG Photo

Members are seen voting at a United Nations Security Council meeting concerning new sanctions on the Democratic People's Republic of Korea at UN Headquarters in New York, US, December 22, 2017. /VCG Photo

As expected, on Dec. 24, the DPRK's foreign ministry issued a statement saying the resolution was nothing but an act of war. Apparently, the new UN resolution came to no avail.

Common sense reveals that Pyongyang's nuclear weapon program has made some major leaps during the past year or so. According to some US sources, the DPRK may be able to produce reliable, nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missiles as soon as 2018. At this stage, persuading DPRK to halt or abandon this program will be very difficult.

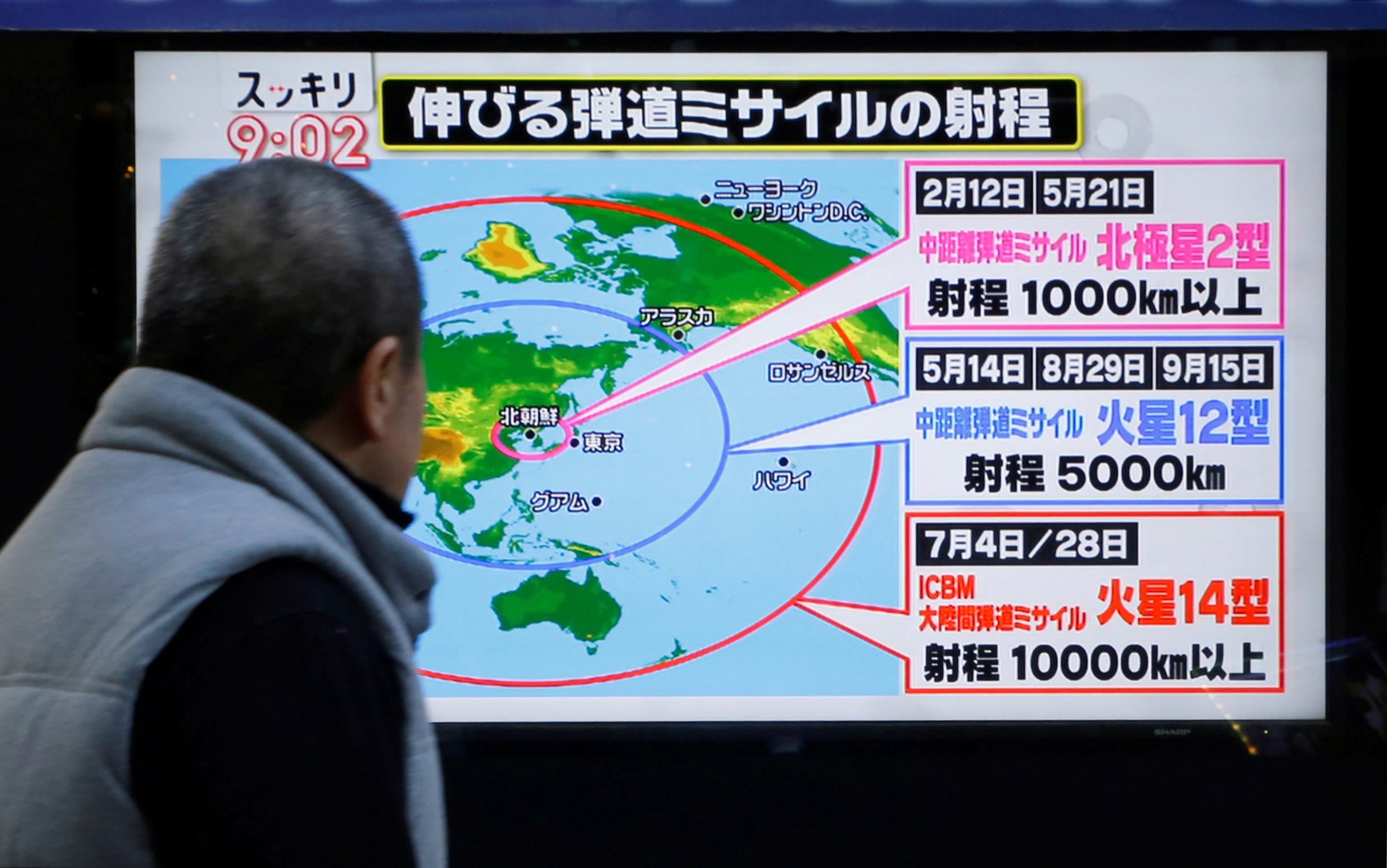

A man looks at a street monitor showing a news report on the DPRK's missile launch, in Tokyo, Japan, on November 29, 2017. /Reuters Photo

A man looks at a street monitor showing a news report on the DPRK's missile launch, in Tokyo, Japan, on November 29, 2017. /Reuters Photo

To make things worse, the US, Japan and South Korea have bent backward to carry out new joint military exercises at the door of the DPRK, which makes the latter even more reluctant to halt new nuclear tests and missile launches, regarding it as the only weapon to deter any outside threat. The question right now is how far the deadlock will go before the worst scenario is realized.

There is no doubt that consecutive sanctions on the DPRK by the UN has failed to address the most outstanding obstacle to resolving the deadly issue, which is the lack of mutual trust among relevant stakeholders, between the DPRK and the United States in particular, and among all six parties at large.

Chinese Deputy Ambassador to the United Nations Wu Haitao (C) attends the United Nations Security Council session on imposing new sanctions on DPRK, New York, US, December 22, 2017. /VCG Photo

Chinese Deputy Ambassador to the United Nations Wu Haitao (C) attends the United Nations Security Council session on imposing new sanctions on DPRK, New York, US, December 22, 2017. /VCG Photo

Past lessons have taught the international community that China’s "dual-track" approach versus the denuclearization of the Peninsula still hold water.

China has been calling for the suspension of Pyongyang's missile and nuclear tests in exchange for the suspension of US-South Korean military drills. Meanwhile, China has been working closely with all stakeholders to bring peaceful resolution to the deadly issue.

Therefore, the United Nations should pitch in to liaise among the stakeholders rather than remaining as a platform to generate new hostilities among the parties concerned.

However, the ultimate step is for the two main stakeholders, the US and the DPRK, to carry out direct talks, while all relevant parties must facilitate conditions for the above talks to be fruitful, without which the Korean nuclear issue will only inch toward the point of no return.

(The author is a senior research fellow at the Pangoal Institution. The article reflects the author’s opinion, not necessarily the views of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3