Opinions

21:09, 28-Mar-2018

Opinion: Automation – the future of global work-life balance

Guest commentary by Elliott Zaagman

Editor's Note: The Boao Asia Forum, which kicks off on April 8, has made innovation one of its top agendas. A future that could be changed by blockchain and automation technology is both exciting and intimidating. Elliott Zaagman, corporate trainer and executive coach, shares his insight on how humans can live peacefully with machines.

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of visiting the headquarters of e-commerce giant JD in the south of Beijing. The sprawling complex is a glimpse into the future. In the building’s main concourse are an unmanned convenience store, a vending machine selling T-shirts, and a display area showing off the company’s sophisticated delivery drones. It’s hard to see such a picture of the future without feeling at once in awe of the possibilities and conveniences that such a world could offer, while also feeling concerned over the human and societal cost of such a rapid and disruptive advancement.

According to a couple of sources close to the company, about seventy percent of JD’s 150,000 employees work in logistics, a large proportion of whom are couriers. As automation increases the efficiencies in this area, many logistics workers will find that the jobs that are plentiful today may be scarce in the future.

JD and its employees are not alone in this regard, but rather experiencing the early stages of a wave that will likely redefine how much of the world makes a living.

Delivery drones may put couriers out of work, as could driverless cars to taxi and truck drivers. Blockchain innovations could make financial intermediary services insignificant, and render some accounting and legal professions obsolete.

Automation’s exponential growth has many experts wondering what the future of work will look like, and how painful the process of getting there may be.

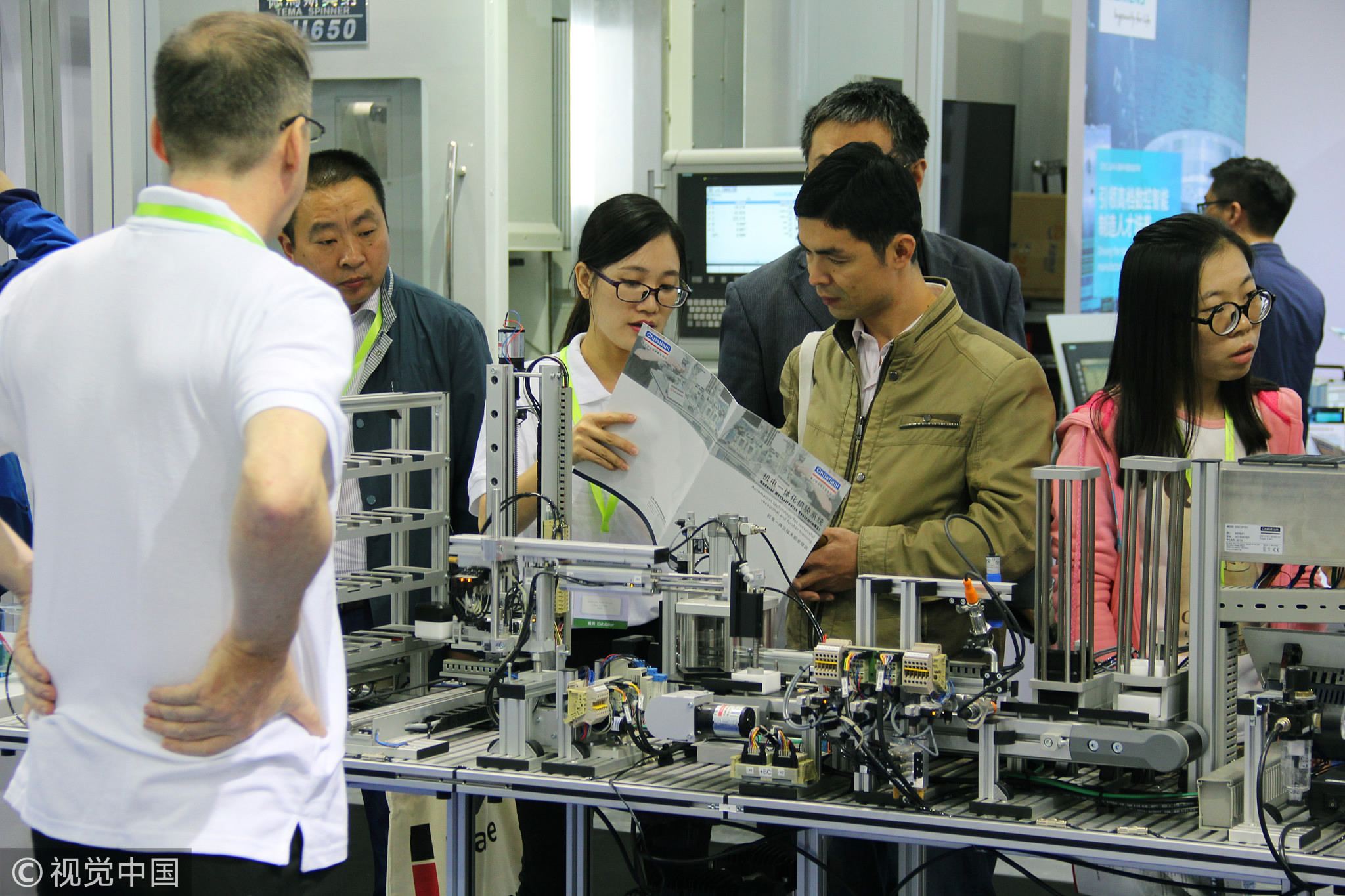

The 2017 World Robot Conference at Beijing, August 23, 2017. /VCG Photo

The 2017 World Robot Conference at Beijing, August 23, 2017. /VCG Photo

Optimists like Alibaba’s Jack Ma talk about a future where people work only four hours per day, and spend their time travelling the world, but acknowledges that the next ten years could be “very painful.” In 2015, a group of top American tech, business, and academic leaders wrote an open letter calling for public policy and organizational changes so that the world can best meet the challenges of this rapidly developing technological age.

How can humanity manage this seismic shift in work and life? It will likely require a broad set of solutions. Here are a few of the most commonly discussed:

Training and education for today’s environment

Today’s knowledge economy moves far faster than it did in the past, requiring more advanced knowledge. But our current methods for education and training are woefully inadequate. Take American universities, for example, where it is not uncommon for students to pay 200,000 US dollars in total for a four-year undergraduate degree. While I am a firm believer in the value of a well-rounded liberal arts education, it is not for everyone, and in an era where we have the world’s information at our fingertips, these degrees often say more about the wealth and class of a student’s family than their ability to do a job. What’s more, in many fields, by the time a student graduates with their degree, the industry in which they are seeking a job is entirely different than it was only four years earlier.

The 2017 Intentional Summit and Exhibition for Vocational Education at Nanjing International Expo Center, China. /VCG Photo

The 2017 Intentional Summit and Exhibition for Vocational Education at Nanjing International Expo Center, China. /VCG Photo

Tech entrepreneurs have scrapped the traditional long-term business plans in favor of “lean startup” approaches that focus on low-cost, high-speed deployment of early versions of a product, receiving feedback from users, and responsive iteration. This way, they build the product with and in the market, rather than wasting time and money in long-term development projects for products that may not be relevant in the end. Education and training should be thought of in the same way. Changing careers for most people should not require years in a classroom and mountains of tuition fees, but should be accessible, cheap, and involve on-the-job experience.

Easing financial burdens

The work of the future will be less stable, requiring that workers be flexible and able to adjust to the changes that come their way. For many, the consumption that has characterized the stereotypical “middle class” lifestyle is accompanied by unnecessary burdens. Owning a personal car, taking out a large mortgage on a home, and other big-ticket possessions and financial obligations can make it more difficult to make the necessary changes in geography and career.

Many have also called for governments to offer a universal basic income, a modest amount of money given to each citizen in order to sustain their basic needs. This would allow some financial “cushion” for people to re-tool during career changes.

Above all, a change in mindset

One of the most difficult aspects of a shifting work landscape is the emotional impact. In my home state of Michigan, in America’s “rust belt,” many of the middle-class blue-collar jobs that so many people once relied on either ceased to exist or did not pay what they once did. While the lives that most of them lived were still far wealthier and more comfortable than most in the world, it was the psychological impact that seemed to do the most damage. Many men grew up planning to support their family on their income alone, but then had to see their wives work as well in order to pay the bills. For others, they had to accept jobs that they once considered “beneath” them.

The abandoned and decaying manufacturing plant of Packard Motor Car in Detroit, Michigan, April 2, 2011. /VCG Photo

The abandoned and decaying manufacturing plant of Packard Motor Car in Detroit, Michigan, April 2, 2011. /VCG Photo

These are not issues of life and death, but for some, this places an emotional burden on themselves and their families that can be destructive. For many of these people, their work gave them dignity, and when the work changed, so did their self-image. Looking at how the job market is projected to change, this will require not only career flexibility, but ego flexibility as well. Those who cling to fixed ideas of self-worth, status, and pride will likely find the future to be a dark place, but those who can humbly accept life as it comes will likely find both success and happiness in the new world of work.

(Elliott Zaagman is a corporate trainer, executive coach, and writer based in Beijing. The article reflects the author’s opinion, not necessarily the views of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3