Opinions

14:34, 06-Nov-2017

Opinion: Trump comes to Japan

Guest commentary by J. Berkshire Miller

This week, US President Donald Trump has kicked off his five-country tour in the Asia-Pacific with the initial visit being to Washington’s strongest alliance in the region – Japan.

The symbolism of Tokyo being the first stop – with all the formal trappings including a courtesy call with Japan’s Emperor – has not been lost on Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Trump and Abe have struck a somewhat unusual personal bond forged through a number summit meetings and a high frequency of phone calls amidst rising tensions on the Korean Peninsula.

US President Donald Trump shakes hands with Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at Kasumigaseki Country Club in Kawagoe, north of Tokyo, on November 5, 2017. /Reuters Photo

US President Donald Trump shakes hands with Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at Kasumigaseki Country Club in Kawagoe, north of Tokyo, on November 5, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Indeed, Abe has now spoken to Trump on the telephone more times in one year than during the entire four-year relationship with former US President Barack Obama.

First off, security issues – especially North Korea – will dominate the agenda and is an area where Japan and the US are largely reading from the same playbook.

Both Abe and Trump have been publicly skeptical about the prospects for dialogue at this point with Pyongyang in order to achieve their common goal of denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

In this sense, the US and Japan will commit to double-downing on deterrence efforts and potentially looking at even deeper sanctions against North Korea. Both sides also have identified the need to work with China – and indeed also increase pressure on Beijing – in order to achieve tangible results on the North Korean issue.

US President Donald Trump addresses members of US military services and Japan Self-Defense Forces at Yokota Air Base in Fussa, on November 5, 2017. /Reuters Photo

US President Donald Trump addresses members of US military services and Japan Self-Defense Forces at Yokota Air Base in Fussa, on November 5, 2017. /Reuters Photo

But Trump’s goal towards turning the screws on the regime of Kim Jong Un in North Korea depends on more than just deterrence and solidarity with Japan. In this sense, this Asian trip is more about Washington’s ability to stitch together meaningful – and sustainable – international commitment to working towards denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula.

This starts of course with Japan and South Korea – as the region’s top US allies and key stakeholders in the brewing crisis. But it will also require a consistent and nuanced approach to China, which remains North Korea’s largest trading partner.

Despite Beijing’s own frustration with the Kim regime, and its incremental efforts to impose new sanctions on the North – their efforts to reign in Pyongyang need to continue and it is crucial that efforts are made to verify the implementation of sanctions.

Aside from North Korea, the US-Japan relationship remains the cornerstone to Washington’s alliance network in the region and continues to actively work with partners in the region – including South Korea, Australia and India – to promote a region unwritten by laws and norms and safeguarded through common strategic visions.

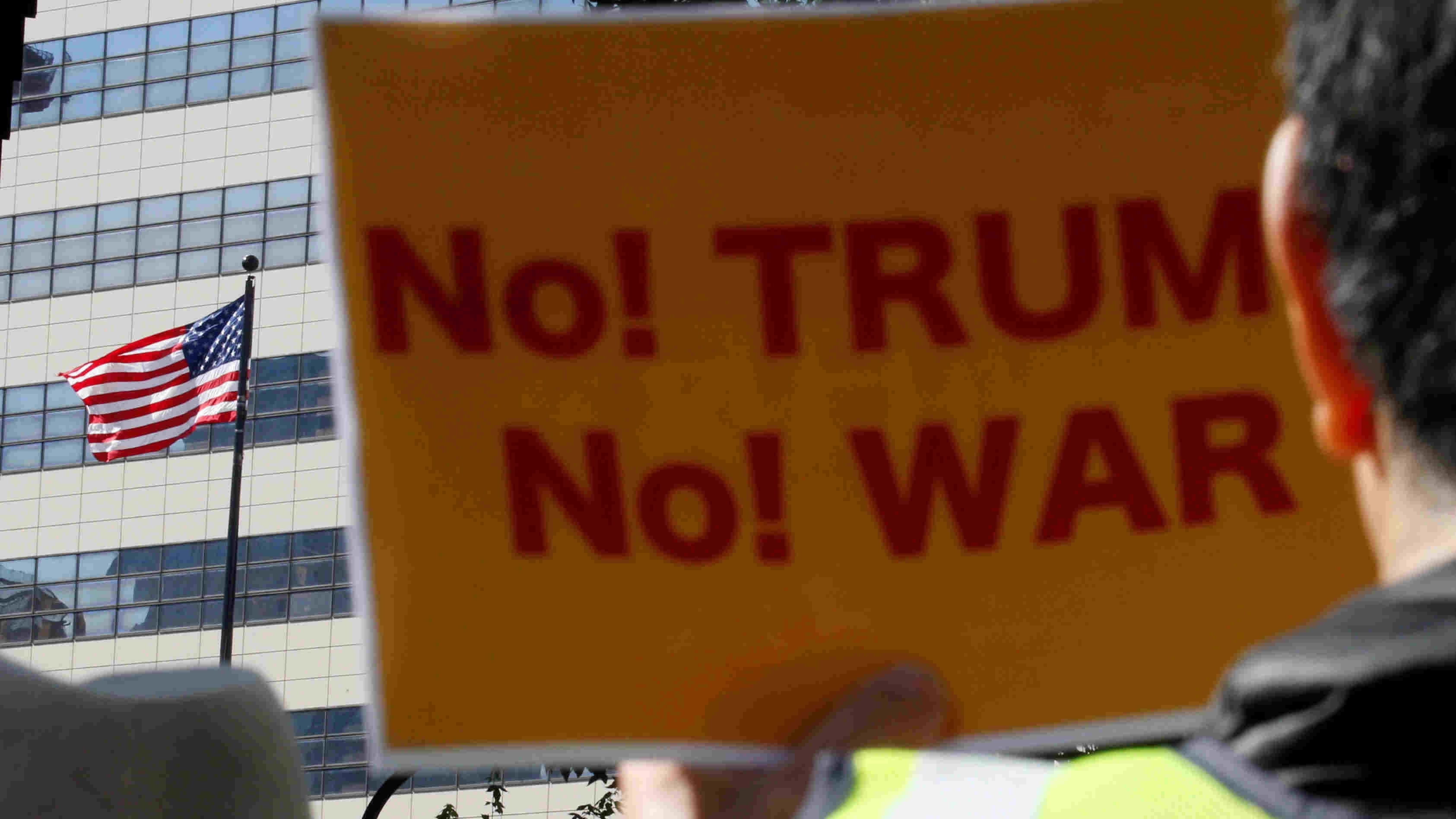

The US national flag flies at the US Embassy as a protester holds a placard during a rally against US President Donald Trump's visit to Tokyo, Japan, on November 3, 2017. /Reuters Photo

The US national flag flies at the US Embassy as a protester holds a placard during a rally against US President Donald Trump's visit to Tokyo, Japan, on November 3, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Based on this, Trump and Abe will continue to push forward on their shared goal of a “free and open Indo-Pacific”. This approach need not come at the expense of China – or any other state in the region – and should be an inclusive strategy where states in the region can work together on the basis of open trade connectivity, open sea lines of communication and the adherence to international laws and norms.

While Japan-US relationships are reaching new levels on the security side, there is less optimism on the economic and trade sides. Trump’s “America First” platform continues to be openly protectionist and has isolated key allies and partners – including Japan – in the region. The clearest example of this was Trump’s withdrawal of the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade pact earlier this year – an agreement that was formerly led and pushed by Washington.

The US retrenchment on the TPP was especially painful for Abe, whose government touted the contentious agreement as a key element of its economic reforms, dubbed Abenomics, to stimulate Japan’s long stagnant economy.

During last month’s US-Japan Economic Dialogue held in Washington DC, US officials strongly indicated their interest to officially start negotiations with Japan on a bilateral free trade administration.

For now, the Abe administration has been cool on the idea and is trying to skillfully delay talk of a bilateral FTA, especially due to the Trump administration’s regional focus on tensions over North Korea and its need to work with Japan on a regional deterrence approach.

But these fault lines on trade are unlikely to go away anytime soon and the Abe administration will need to continue to carefully balance its position and principles on free trade on one hand, with its desire not to create instability in the broader relationship and alliance with Washington.

(The author is a senior fellow with the Tokyo-based Asian Forum Japan and the director of the Ottawa-based Council on International Policy. The article reflects the authors' opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3