Culture & Sports

19:51, 27-Jul-2017

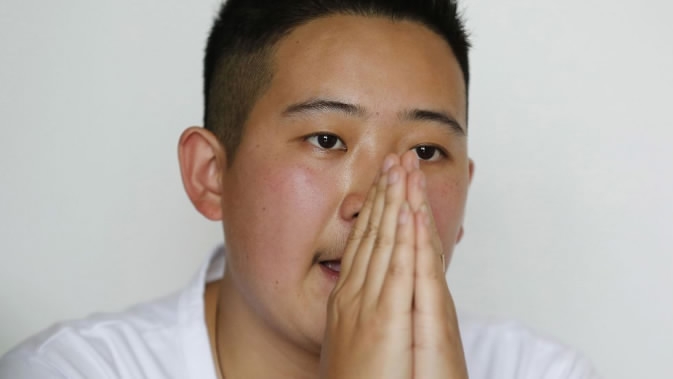

Chinese transgender man fights for job equality

A 28-year-old transgender man nicknamed "Mr. C" has become the public face in the fight for job equality in China, where sexual and gender minorities are only beginning to emerge from virtual invisibility.

Mr. C, who keeps his real name secret, is fighting in court his dismissal from a medical testing center and seeking for a ruling stating that no one should be discriminated against gender identity or sexual orientation.

“I am carrying the hopes of many, many people on my shoulders,” said Mr. C, who’s been both praised and vilified since filing the country’s first ever lawsuit against transgender job discrimination earlier this year.

“Many people are working towards (employment equality). I cannot let them down. There are many members in our group who are unwilling to or dare not step forward, but they are watching,” he added.

A screenshot of VICE interviewing C.

A screenshot of VICE interviewing C.

Born female, Mr. C grew up in the southwestern province of Guizhou, a more conservative environment than the eastern cities of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. He didn’t even come across the term “transgender” until 21, when he was finally able to best describe his gender identity.

Building on that momentum, Mr. C hopes to nudge the government toward recognizing and protecting LGBT rights.

After graduating from college in 2010, Mr. C continued to appear as a woman when applying for jobs. That all changed in 2013, when he began dressing as a man, wearing a buzz cut and growing a mustache.

A couple take a "selfie" at Pink Dot, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) carnival in the West Kowloon district of Hong Kong on September 25, 2016. /AFP Photo

A couple take a "selfie" at Pink Dot, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) carnival in the West Kowloon district of Hong Kong on September 25, 2016. /AFP Photo

In 2015, he applied for a sales job with Ciming Health Exam Center in the provincial capital of Guiyang, but was let go at the end of the eight-day trial. He believes he was dismissed because of his gender expression, but the company argued his job performance had been substandard.

Mr. C took the dispute to a local labor arbitration panel, which ruled in early May that his dismissal had been legal, while ordering Ciming to pay him 62 dollars in back wages.

Days later, Mr. C filed his case in a local court, which has yet to put it on the docket.

“Now I place my hopes with the law,” he said. “I will do whatever I can to fight to the end.”

A photo from the Taiwan Pride event in 2017. /AFP Photo

A photo from the Taiwan Pride event in 2017. /AFP Photo

While still relatively conservative, Chinese society is slowly becoming more accepting of gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender people, particularly among the younger generation.

That’s encouraged some members of sexual and gender minorities to come forward and demand their legal rights, with mixed results.

In 2014, a Beijing court ruled that “conversion therapy” intended to alter sexuality was illegal.

And a court in central Hunan Province shot down an attempt by a gay couple to register their marriage in April.

Although it was never specifically outlawed, since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, alternative expressions of sexuality have tended to be associated with corruption and decadence.

Those caught up in police raids could be jailed on charges of hooliganism or even executed during particularly severe crackdowns.

A Chinese transgender Chao Xiaomi. /Sina Weibo Photo from Chao Xiaomi

A Chinese transgender Chao Xiaomi. /Sina Weibo Photo from Chao Xiaomi

However, in 2001, the Chinese Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.

Police raids on LGBT gatherings largely came to a halt, as long as they remained low-profile.

Empowered by the Internet and social media, LGBT groups in different cities began networking, leading to calls for stronger legal protections.

China has no laws addressing employment discrimination, and efforts are ongoing to enact laws protecting minorities in the workplace.

A recent United Nations Development Program survey found that only around 5 percent of sexual and gender minorities in China choose to come out in public, and that the workplace can become especially awkward and unpleasant after they do so.

“The findings are clear. Sexual and gender minority people in China still live in the shadows,” said the report, which drew on findings from a two-month survey of more than 30,000 people conducted in late 2015.

A couple pose for a portrait at Pink Dot, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) carnival in the West Kowloon district of Hong Kong on September 25, 2016. /AFP Photo

A couple pose for a portrait at Pink Dot, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual and intersex (LGBTI) carnival in the West Kowloon district of Hong Kong on September 25, 2016. /AFP Photo

Many LGBT respondents complained of losing jobs through discrimination and had therefore lowered their career expectations and had less motivation to acquire new skills, according to the report.

Li Yinhe, a prominent Chinese sexologist, said transgender people in particular are more likely to face workplace discrimination because of how they look and dress.

“It’s harder for them to disguise themselves,” Li said.

Given the prevailing sentiments, Mr. C’s case has brought important public scrutiny to long-ignored issues, Li said.

As in Western countries, the business community, rather than the government, is leading the way in China in pushing for equal opportunities, said Steven Bielinski, who has organized social events in Beijing and Shanghai to connect employers with members of the LGBT community.

All gender toilet in Beijing. /Photo from web

All gender toilet in Beijing. /Photo from web

“Here in China I think the LGBT business issue has just reached a tipping point,” Bielinski said. “More and more companies are thinking about what the LGBT community means for business in terms of talent and market.”

A job fair in Shanghai on a May weekend attracted a total of 34 companies – twice as many as the year before – including Chinese car-hailing app Didi Chuxing, the career site Kanzhun.com, and multinationals such as 3M, Citigroup and the Boston Consulting Group.

It was also the first time that Chinese companies made an appearance, Bielinski said.

Despite the Interest, Bielinski cautioned against being too optimistic.

Organizers declined to allow Associated Press journalists to attend the fairs out of privacy concerns.

“It’s just the start,” Bielinski said.

(Source: AP)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3