China

14:21, 13-Jan-2018

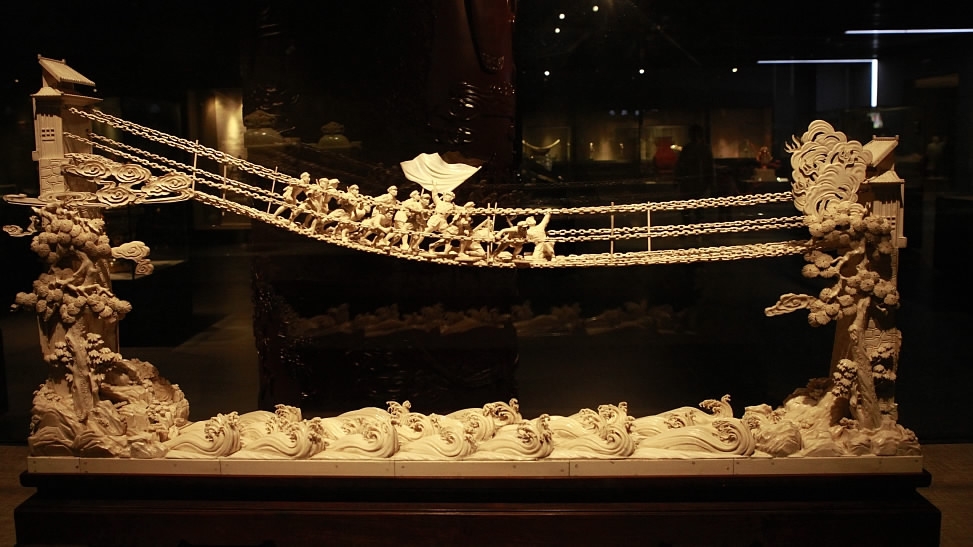

Is Chinese ivory carving nearing its end?

CGTN

The craft of ivory carving in China dates back thousands of years, but it just might die out with the government-imposed ban on the ivory trade.

The art is well known to many in the country, peaking during the Qing Dynasty several hundred years ago, and was even designated as a state-level intangible cultural heritage in 2006.

Craftsman carving ivory /Photo via Xinhua

Craftsman carving ivory /Photo via Xinhua

However, buying ivory in China has been controversial, much less making items out of the elephant tusk, since wildlife charities say the ivory comes from poaching, which results in the illegal killing or capturing of elephants.

According to the state-run Xinhua news agency, 67 ivory-carving factories were shut down in March 2017, while the remaining 105 were closed at the end of last year.

The craft requires intricate skill, with only about ten percent of young apprentices becoming qualified carvers. So will ivory carving slowly die out, along with its complex techniques?

Li Chunke, who retired from an ivory crafting factory, went back to take a picture of his work before it closed . /Photo via VCG

Li Chunke, who retired from an ivory crafting factory, went back to take a picture of his work before it closed . /Photo via VCG

To sustain this centuries-old tradition, Chinese artisans have turned to other sources, such as the tusks of extinct mammoths, a practice that has been touted as an ethical alternative since it does not come from the poaching of live animals.

Zhang Minhui, a recognized ivory carving master in China, started exploring the use of ox bones two decades ago, when China-made ivory began to lose its market in Western countries after the Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora banned ivory trade in 1989.

“As we finished our last piece of legal stock piece, we will use mammoth tusks and ox bones, which are much bigger and cheaper,” Zhang told the Guardian.

“The texture and the hardness are perfect for carving. Its colors are appealing to Chinese.”

He also invented a technique to clean the mildew from ox bones while retaining their gloss, and to put hundreds of small bones together to imitate elephant ivory.

Li Chunke, a 68-year-old ivory craftsman, began carving ivory after leaving school at 15.

“What makes our country great is that its traditional culture still exists. If it disappears, it will be a loss for the whole world,” he told the Telegraph.

Today, he loves carving images of people and conveys emotion in his figures, as well as creating impossibly intricate images of flowers, birds, and mountains on mammoth tusks.

Zheng Suisheng, another Chinese ivory carver, also believes that mammoth tusks could help preserve the ancient carving industry.

Even though the skills for the craft has been passed down for generations, Zheng has not yet taught his son the family trade.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3