China

08:56, 10-Mar-2018

Ask China: Will child abusers get the punishment they deserve?

CGTN's Li Tianfu and Wang Xuejing

“My daughter likes it there. She always says ‘I like my teacher’ after returning home from her kindergarten,” Zou Ling told CGTN when asked about how her four-year-old daughter feels about her nursery.

Zou could be satisfied with her choice of daycare, but a good lot of parents around China might not share that peace of mind.

A string of high-profile child abuse cases at preschools around China last year left many wondering what exactly happens when children are left with guardians whose role is to protect them.

In Shanghai, kindergarten teachers were caught on camera pushing children violently, with some being forced to consume wasabi. In Wuhan, central China’s Hubei Province, caretakers were accused of slamming youngsters and pulling their ears, while in the southwestern municipality of Chongqing, one teacher was fired for coercing children to slap each other.

However, it was the Red Yellow Blue (RYB) kindergarten scandal in Beijing that shook the whole country in late 2017, triggering public backlash and prompting inspection of daycare centers nationwide.

The incidents, as many as 19 in 2017 according to estimates, left people in the country wondering: Will child abusers get the punishment they deserve?

A shocking scandal

The Xintiandi branch of the RYB Kindergarten in Chaoyang District, Beijing. /VCG Photo

The Xintiandi branch of the RYB Kindergarten in Chaoyang District, Beijing. /VCG Photo

Allegations that children at a RYB nursery in Beijing’s affluent Chaoyang District were pricked with needles led to the arrest of a teacher, the removal of the nursery’s branch head, and the fall of the company’s shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

“When I first heard about the RYB kindergarten abuse scandal, I was shocked. It was hard to believe. Only by watching the news over and over again could I believe that what I was hearing was true,” Zou said.

“I didn’t dare to tell my daughter about how children of her age were being treated at the kindergarten.”

Zou Ling talks about her feelings after reading the reports about the RYB child abuse scandal. /CGTN Photo

Zou Ling talks about her feelings after reading the reports about the RYB child abuse scandal. /CGTN Photo

The teacher, identified by her surname Liu, was detained for allegedly using needles to discipline toddlers who did not sleep on time. Beijing police said the 22-year-old woman was arrested on suspicion of “mistreating persons in her care.”

Broadening the scope of offenses

“I didn’t know there were laws against child abuse in particular,” Zou said. But there is one thing she knows for sure – that the suspect should be brought to justice.

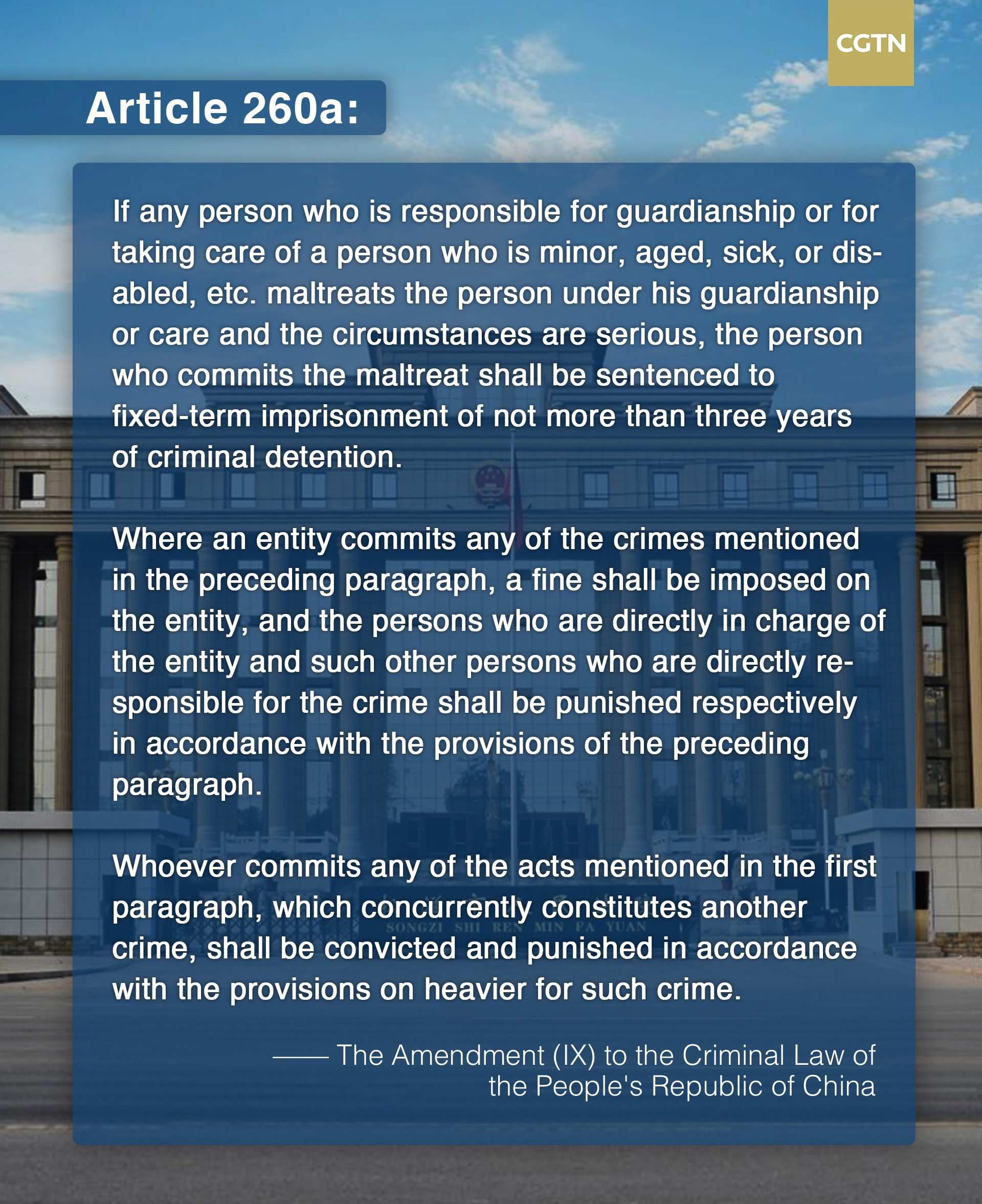

“In the case, the Beijing Chaoyang District People's Procuratorate approved the arrest of the suspect on suspicion of abusing those in their care in accordance with the newly added offense in Article 260a of the Amendment (IX) to the Criminal Law of China,” Zhu Yue, a partner at the East & Concord Partners and criminal defense lawyer with over 20 years of experience, told CGTN.

China’s top legislature adopted the ninth amendment to the country’s criminal law on August 29, 2015. One of the applauded moves was extending criminal responsibility against certain offenses to children from family members only to their guardians and caretakers.

“Prior to the declaration of the amendment, the suspect would definitely not be charged with such a crime,” Zhu said, adding that the suspect in this case would have been charged with intentional injury.

However, the broad definition of intentional injury could have made criminal conviction difficult.

“Viewing the current information at hand, the injuries of the children are not severe enough to be identified as minor injuries or even slight wounds. Therefore, if there is no such crime relating to Amendment (IX), then it is very hard to file a criminal charge against the suspect,” he said.

The previous edition of Article 260 stipulated that any offense would be handled “only upon complaint,” while the revised provision adds, “Unless the victim is not capable of or unable to bring a complaint due to coercion or intimidation.”

In the RYB child abuse scandal, the victims were three or four years of age, most of whom are not capable of stating the incident as clearly as adults. With the amendment already in force, the perpetrators can be prosecuted without the children and their families filing a complaint.

Role of legislation

Since the criminal law came into force in 1997, China has made 10 amendments to the penal code with the latest being promulgated last November.

“The 10 amendments reflect that the legislation of the criminal law by China's top legislature has advanced with the times. We can find that each amendment reflects the public will at the time, and the issues of common concern,” Zhu said.

“The ninth amendment to the criminal law features a broad extension and increased specificity as it has covered many social concerns.”

Zhu Yue, partner of the East & Concord Partners and criminal defense lawyer. /CGTN Photo

Zhu Yue, partner of the East & Concord Partners and criminal defense lawyer. /CGTN Photo

From the child abuse case at a Shanghai daycare to the RYB scandal, incidents involving children are no rare occurrences, causing concerns among parents about the safety of their offspring. The revised and complemented Article 260 may deter caretakers from abusing children, Zhu said.

“Society has undergone comprehensive development. So has legislation,” Zhu has said.

During this year’s Two Sessions, deputies to the 13th National People’s Congress (NPC) will continue their work on child protection.

NPC deputy Zhu Lieyu, also a lawyer from south China’s Guangdong Province, said in an interview with Shanghai-based The Paper that he will submit a proposal to the top legislature to add the crime of child abuse to the penal code and build up a comprehensive child protection system to prevent such crimes.

(Cameraman Zhang Wanbao, copyedited by Nadim Diab and Josh McNally, graphic designed by Fan Chenxiao, animation made by Ran Boqiang)

This is one episode of the "Ask China" series. For more:

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3