Tech & Sci

10:23, 04-Jul-2017

Rise of frogs began after extinction of dinosaurs: study

Most of the frogs alive today may owe a "big thank you" to the mass extinction that wiped out dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

A new study by Chinese and American biologists shows that 88 percent of today's frog species are descended from just three lineages that survived the calamity, likely caused by an asteroid or comet striking the Earth.

"Frogs have been around for well over 200 million years, but this study shows it wasn't until the extinction of the dinosaurs that we had this burst of frog diversity that resulted in the vast majority of frogs we see today," said study co-author David Blackburn, associate curator of amphibians and reptiles at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the University of Florida campus.

Comic titled "Doom of Dinosaurs, Rise of Frogs" /Florida Museum of Natural History Photo

Comic titled "Doom of Dinosaurs, Rise of Frogs" /Florida Museum of Natural History Photo

This finding, published Monday in the US journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, "was totally unexpected," Blackburn said.

The swift rise of frogs after the massive die-off was likely due to the fact that so many environmental niches were available after the animals occupying them disappeared.

"We think there were massive alterations of ecosystems at that time, including widespread destruction of forests," Blackburn said. "But frogs are pretty good at eking out a living in microhabitats, and as forests and tropical ecosystems rebounded, they quickly took advantage of those new ecological opportunities."

Herpetologist David Blackburn, with a Goliath frog from the museum’s collection, co-authored a study that presents a new frog tree of life. /Florida Museum of Natural History Photo

Herpetologist David Blackburn, with a Goliath frog from the museum’s collection, co-authored a study that presents a new frog tree of life. /Florida Museum of Natural History Photo

Today, there are more than 6,700 known frog species, representing 55 families and living in a wide range of habitats from trees to aquatic environments to underground.

For this study, Blackburn joined researchers from Sun Yat-Sen University in China, the University of Texas at Austin and the University of California, Berkeley in the US to tackle the mystery of frog evolution with a dataset seven times larger than that used in prior research.

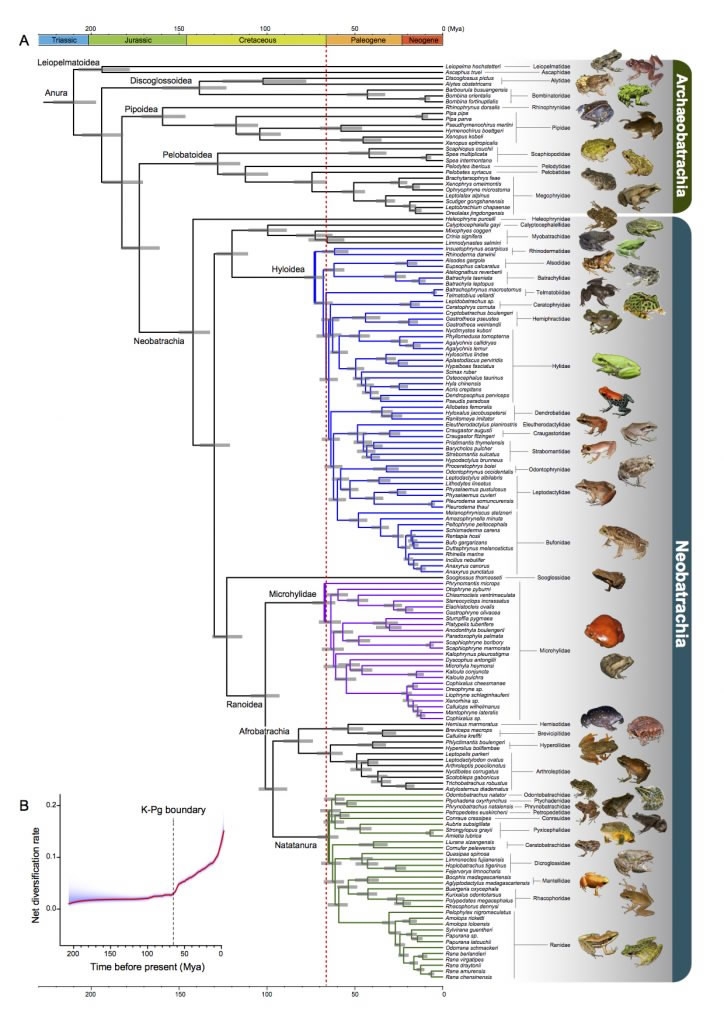

The team sampled a core set of 95 nuclear genes from 156 frog species, combining this with previously published genetic data on an additional 145 species to build the most complete frog family tree yet.

The analysis that generated this frog tree of life shows 88 percent of modern frogs evolved after the mass extinction that killed non-avian dinosaurs, marked here by a dotted red line. /Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Photo

The analysis that generated this frog tree of life shows 88 percent of modern frogs evolved after the mass extinction that killed non-avian dinosaurs, marked here by a dotted red line. /Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Photo

While the extinction event opened new opportunities for frogs, notably leading to the evolution of tree frogs worldwide, it snuffed out many frog lineages, particularly in North America, the team said.

The study also indicates that global frog distribution tracks the breakup of the supercontinents, beginning with Pangea about 200 million years ago and then, Gondwana, which split into South America and Africa.

The data suggested frogs likely used Antarctica, not yet encased in ice sheets, as a stepping stone from South America to Australia.

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

While the survival and subsequent comeback of frogs testifies to their resilience, Zhang said, their current vulnerability to disease, habitat loss and degradation is a cause for concern.

"I think the most exciting thing about our study is that we show that frogs are such a strong animal group. They survived from the mass extinction that completely erased dinosaurs and boomed back quickly," he said.

"However, frog species are declining nowadays because humans are destroying their habitats. Does that mean humans are making a huge extinction event even stronger than this one? We need to think about it."

(Source: Xinhua)

12054km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3