11:08, 05-Apr-2019

In the Name of Science: Body donations contribute to research work in US

Updated

11:00, 08-Apr-2019

03:12

And as China marks Tomb Sweeping Day, we look over to the U.S. at what's becoming a modern custom in managing life's end. Cremation has now become as common as burials in the U.S., perhaps even more so. But families do have another option. Some Americans donate their bodies to science -- some in a very unusual way. CGTN's Hendrik Sybrandy reports from the state of Colorado.

It's often said, and it's true, that death is inevitable. But what happens when that moment finally arrives? Some people donate their bodies for scientific research.

"Yeah, that's something I've thought about in the past."

"Some people are just freaked out by that but I'm gone. What difference does it make?"

Some of those donors happen to end up here.

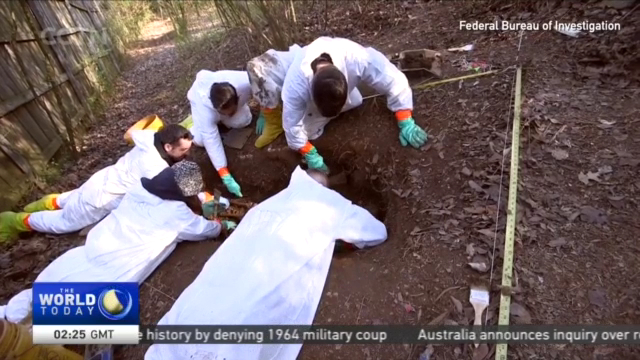

Melissa Connor runs the Forensic Investigation Research Station near Grand Junction, Colorado. Here, just out of public view, lie some 50 human bodies, right out in the open.

MELISSA CONNOR, DIRECTOR FORENSIC INVESTIGATION RESEARCH STATION "Mostly they're laying on their back, in the nude, on the ground."

They're objects of study as they slowly decompose.

"What we're looking at is ways to tell how long people have been dead."

The 6-year-old facility belongs to Colorado Mesa University and specializes in forensic anthropology or the study of human remains. It turns out the way bodies decompose can tell us a lot about when and even how people died. That's key for investigators of crimes and missing persons. Time of death can be obvious.

"But the longer somebody has been dead, the more difficult it is to estimate that post-mortem interval, but often the more critical, the more important it is."

These facilities, there are half a dozen of them, mostly in the U.S., are often called "body farms", after a 1994 novel by the same name. It's a term Connor is a bit uncomfortable with.

"At all times if there's one thing we want to do is show that we respect the people who gave us their bodies to study."

Gave their bodies for education, she says, or simply to end up in a scenic place like this.

HENDRIK SYBRANDY WHITEWATER, COLORADO "As you might imagine, security here is pretty tight. This three-meter tall fence is topped with razor wire. There are surveillance cameras. Only staff and students are allowed inside."

ALEX SMITH LAB MANAGER "We've got a little petri dish with some liver for the maggot to feed on as it grows."

A lot of the work here centers around insects, which arrive and disappear at various stages of decomposition and can tell a lot about how long a person has been dead. Climate also greatly affects the process.

"What we're finding out is how much we don't know."

This map shows how the bodies are laid out and what year they arrived. Eventually, the skeletal remains are brought back into the lab. Connor has met many of the donors.

"You know I think it's nice to know some of these folks ahead of time."

And she's gotten used to the unusual aspects of her job, focusing on what current and future investigators and medical examiners can learn from her research. Like death, she suggests, that too is inevitable. Hendrik Sybrandy, CGTN, Whitewater, Colorado.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3