Tech & Sci

15:49, 07-Mar-2018

US allows trophy hunting on case-by-case basis, in latest flip-flop

Alok Gupta

In a major blow to global efforts to ban ivory trading, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has allowed imports of hunting trophies from elephants and other wild animals primarily from African countries.

The decision comes despite President Donald Trump’s pledge to impose a ban on such imports. In a memorandum released on March 1, maintained, “The Service intends to grant or deny permits to import a sport-hunted trophy on a case-by-case basis.”

Earlier, the department had lifted a blanket ban implemented by the Obama administration on imports of elephant trophies from South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Botswana, and Namibia. The decision was then rolled back after Trump intervened and termed the hunting of wild animals a “horror show.”

Environmental groups working to ensure a global ban on ivory appeared shocked over the government’s latest flip-flop. John Baker, chief program officer, WildAid, San Francisco told CGTN, “We are concerned that a lack of rigorous, explicit and enforceable standards will lead to dangerous loopholes for ivory and other illegal wildlife entering the commercial trade.”

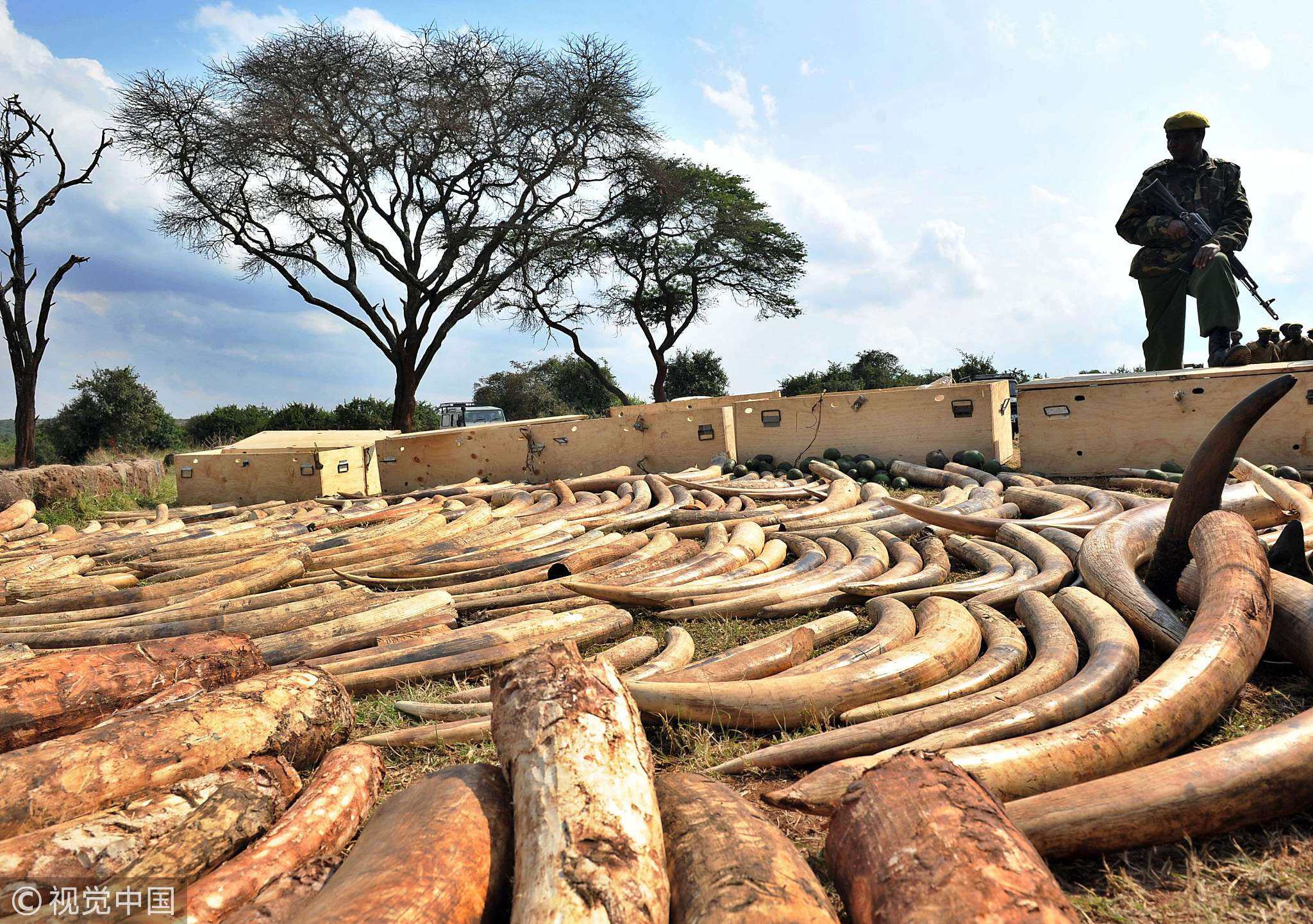

A Kenyan Wildlife Services ranger standing guard over an ivory haul seized as it transited through Jomo Kenyatta Airport in Nairobi. /VCG Photo

A Kenyan Wildlife Services ranger standing guard over an ivory haul seized as it transited through Jomo Kenyatta Airport in Nairobi. /VCG Photo

In 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping and then US President Barack Obama jointly made a historic announcement that the two countries would entirely ban ivory trade in their domestic markets.

In China, ivory is a status symbol and demand is driven by the fact that items like ivory chopsticks and intricately designed jewelry have been a big part of the culture. Meanwhile, in the US, the ivory trade is dominated by trophies from legal sports hunting.

Hong Kong, the largest market for ivory, voted to ban the “white gold” in January.

The illegal ivory trade, according to WWF, WildAid, and TRAFFIC, is fueling poaching of nearly 20,000 African elephants every year.

The issue of trophy hunting is divisive among conservationists.

Well-managed trophy hunting can generate critically needed incentives and revenue for the government and landowners to maintain and restore wildlife and land use and to carry out conservation, according to a recommendation paper written by the secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

“It can return much-needed income, jobs, and other important economic and social benefits to indigenous and local communities in places where these benefits are often scarce,” the secretariat said.

On the other hand, many groups say such trophy hunting boosts global demand for ivory and wildlife hides. In the case of ivory, traders exploit a loophole in the CITES which prohibits international, but not domestic, trade in ivory. The convention covers ivory processed after 1990 – or “pre-convention” ivory.

Under the accord, governments issue licenses identifying pre-convention ivory pieces. But campaigners say traders in many countries including the EU and Japan routinely forge the documentation to evade prosecution.

In the past year, Hong Kong and UK Prime Minister Theresa May have announced that they would work closely with the Chinese mainland to control the ivory trade, motivating wildlife experts to start campaigning to ensure a global ban on ivory.

“The US decision represents a worrying step backward compared to global leadership in wildlife conservation,” Baker said.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3