Tech & Sci

12:15, 10-Aug-2017

Study shows moon's magnetic field lasts 1 billion years longer than thought

New evidence from ancient lunar rocks suggests that the Moon's magnetic field may have lasted at least one billion years longer than once thought, researchers said Wednesday.

Currently, the Moon does not possess a global magnetic field. According to past studies, however, an active lunar core dynamo, or energy conversion process responsible for generating the Moon's magnetic field, was present between 4.25 and 3.56 billion years (Ga) ago with a field intensity similar to that of the Earth.

"The field intensity then precipitously declined by at least an order of magnitude (possibly even to zero) by ~3.19 Ga," wrote the study published in the journal Science Advances.

"It is unknown whether this decrease reflects total cessation of the dynamo or whether the dynamo persisted beyond 3.56 Ga in a markedly weakened state," it said.

The lunar rock sample from the Apollo 15 mission. The rock consists of basalt fragments welded together by a dark glassy matrix produced by melting caused by a meteorite impact. /NASA Photo

The lunar rock sample from the Apollo 15 mission. The rock consists of basalt fragments welded together by a dark glassy matrix produced by melting caused by a meteorite impact. /NASA Photo

For the study, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Rutgers University analyzed a lunar rock collected by the Apollo 15 crew on Aug. 1, 1971, on the southern rim of Dune Crater within eastern Mare Imbrium.

The small rock -- partially coated with melted glass -- likely formed about one billion to 2.5 billion years ago during a meteor impact on the lunar surface, and the researchers believed it recorded the magnetic field to which it was exposed.

And the analysis showed a relatively weak magnetic field of about five microtesla at the time of its formation.

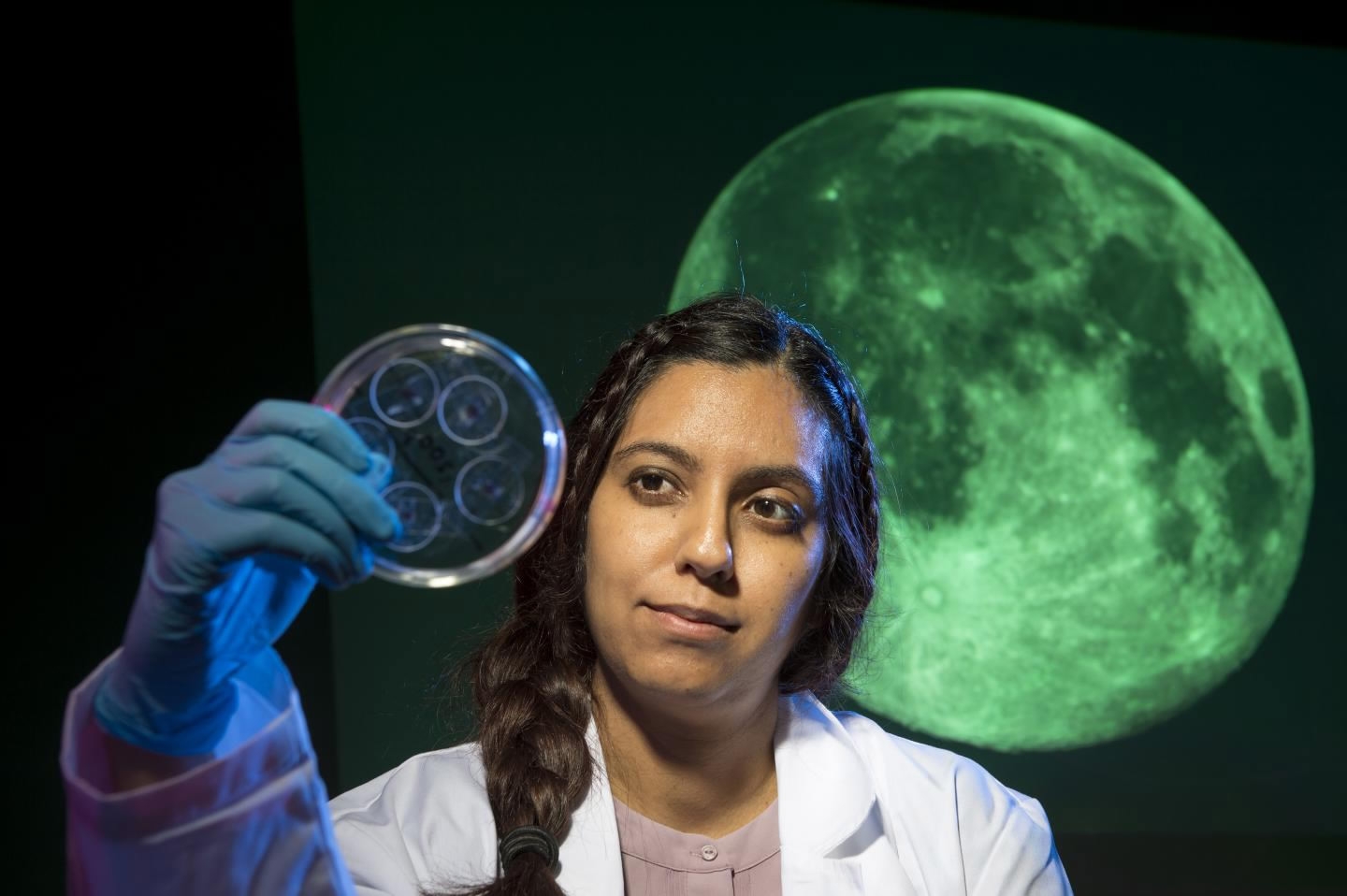

Sonia Tikoo, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, looks at moon rock samples in a Petri dish. /Rutgers University Photo

Sonia Tikoo, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, looks at moon rock samples in a Petri dish. /Rutgers University Photo

That's around 10 times weaker than Earth's current magnetic field but still 1,000 times larger than fields in interplanetary space today.

That means after the Moon's magnetic field dwindled, it nonetheless persisted for at least another billion years, existing for a total of at least two billion years, the researchers said.

The researchers are planning to analyze more lunar rocks to determine when the dynamo died off completely.

"Today the Moon's field is essentially zero," study author Benjamin Weiss, professor of planetary sciences of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said. "And we now know it turned off somewhere between the formation of this rock and today."

Source(s): Xinhua News Agency

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3