Culture

10:18, 29-Mar-2018

Longquan Celadon: The 'jade' in Chinese porcelain

By Ai Yan

China is well-known as the birthplace of ceramics, which could even be reckoned from its English name – a synonym for porcelain.

The country’s international prestige in ceramic producing has been on the rise since the eighth century, when porcelains were exported to foreign countries through the land and maritime silk roads.

And this impression was reinforced in 2009, when the Longquan Celadon firing technology was enlisted into UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list as the only porcelain-related item.

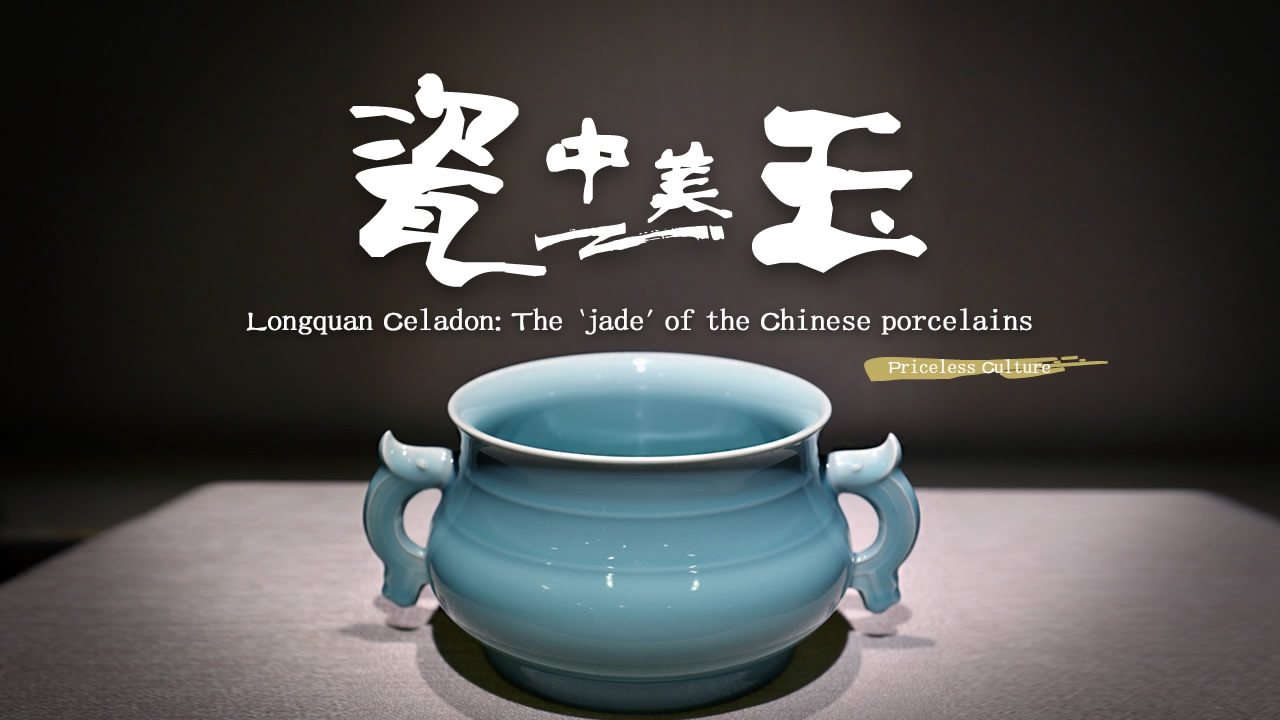

An artifact of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

An artifact of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

Among a sea of diverse ceramic productions with complicated craftsmanship, delicate and versatile forms and thousands of years of history, what makes the Longquan Celadon stand out, and why is it dubbed as “the beautiful jade of Chinese porcelain”?

To answer those questions, one need to take a closer look - not only its glittering green glaze, but also the stories behind it.

What makes Longquan Celadon shine?

The history of Longquan Celadon can be dated back to the year 220, during the Three Kingdom period, but it did not reach its golden era until the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), when the plum-green and the jade-green glazes were finally fired.

An artifact of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

An artifact of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

The glaze is exactly what makes the Celadon shine – the color comes from the iron oxide, which varies according to different temperatures. The temperature needs to be above 1,000 degrees Celsius or even 1,300 degrees Celsius to produce the right colors, which varies from plum-green to yellowish brown.

But the outlooks of Longquan Celadon products can be quite different, as they can also be divided into Geyao Kiln and Diyao Kiln products, which were said to have originated from a pair of brothers, in accordance to their craftsmanship and characters.

An artifact made by techniques of both Geyao Kiln and Diyao Kiln. /VCG Photo

An artifact made by techniques of both Geyao Kiln and Diyao Kiln. /VCG Photo

Geyao products - also known as “elder brother celadon” - with its black clay mounds and covered crackled glaze, carry a sense of solemnity and decorum. The Geyao Kiln is also one of China’s Five Great Kilns. Diyao products - “younger brother celadon” - though not as highly recognized as the Geyao, earned international fame instead.

Compared with its brother, the Diyao products are more smooth and shiny - “green like a jade and bright like a mirror” - and were well received after being exported to nearby countries. Aside from Asian countries such as Japan and Korea, Longquan Celadon also captured quite a number of enthusiastic fans in Europe, especially in France, where it has the present name “celadon” taken from a character in the French pastoral romance “L'Astrée” by Honoré d'Urfé, who wore pale green ribbons.

A bumpy history: Rise, fall, and rejuvenation

A visitor takes photos of Longquan Celadon vase on display. /VCG Photo

A visitor takes photos of Longquan Celadon vase on display. /VCG Photo

However, despite its popularity, the development of Longquan Celadon was inconsistent, before it was fully rejuvenated in the 20th century.

The golden era of Longquan Celadon was in the Southern Song Dynasty and the following Yuan Dynasty, when there were more than 300 kilns in Longquan city, which is in today’s Zhejiang Province.

Many of the ceramics produced by the kilns in Longquan were used daily by the upper classes, including the top rulers at that time. Influenced by the high artistic aestheticism of the Song emperors, most of the Longquan Celadon products have a primitive simplicity and are rarely decorated. Meanwhile, their fine and smooth quality and outlines were also a manifestation of the then fashion.

Artifacts of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

Artifacts of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

However, the kilns in Longquan started to decline in the Ming Dynasty due to depression in the export market and the rise of new porcelains. The kilns were nearly all closed down as of the early 20th century.

It is not until the year of 1957, when China’s then premier Zhou Enlai asked local experts and craftsmen to re-ignite the kilns for Longquan Celadon production that the ceramic was given a second life.

Since then, based on traditional technologies and craftsmanship, many designers, experts and artists were attracted to the city of Longquan, contributing to the inheritance and innovation of the celadon.

A visitor watch an artifact of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

A visitor watch an artifact of Longquan Celadon on display. /VCG Photo

Local government even invested 120 million yuan (19 million US dollars) in 2012 towards developing the kilns, to initiate the project of building the “Township of the Celadon”. As of 2015, the annual turnover of the celadon industry reached two billion yuan (320 million US dollars), greatly contributing to the local economy.

Recently, the new products by the celadon masters have recaptured the attention of porcelain enthusiasts - not only domestically but also internationally. Longquan Celadon products now appear frequently at significant occasions including international conferences, such as the G20 summit in Hangzhou and the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing.

Celadon tea set used for bruising tea. /VCG Photo

Celadon tea set used for bruising tea. /VCG Photo

According to the local newspaper, at least 16,000 people live on their income from producing celadon in Longquan city, allowing for further possibility in developing and discussing the progresses and innovations in the craftsmanship.

Nowadays, vases, teapots, cups, sculptures and much more, all from Longquan Celadon, have not only re-appeared on the table of many Chinese, but also appear on display at the exhibitions and in the museums.

And one thing is for sure: The “jade of the Chinese porcelain” will continue to shine, not only in China, but also around the world.

(Video by Zhou Yun; head image designing by Gao Hongmei)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3