Business

17:53, 01-Dec-2017

Emerging markets debt is so hot, some investors can’t get enough

CGTN

In their hunt for yield, some investors have been venturing into offerings as exotic as Tajikistan’s sovereign bond or Iraq’s first sovereign debt sale without US backing in more than a decade only to find out that even those are pricey and hard to get.

Even as emerging markets bonds lost some ground in recent weeks in the secondary market, primary offers from Panamanian bank Multibank Inc MULTB.UL, the Bahamas, and a 30-year Nigerian bond have been well oversubscribed, following a trend of lower sovereign and corporate yields.

The sellers’ market is good news for emerging market borrowers, giving them access to funds at rates once afforded only to “investment grade” issuers. But it could lead to mispricing of riskier assets and threaten valuations in the long-term by encouraging borrowers to cut coupons on future issues.

Right now it is forcing some funds to scale back.

Samy Muaddi, a portfolio manager of T Rowe Price’s Emerging Markets Corporate Bond Fund, said he has reduced his purchases of initial bond offerings as 2017 has progressed.

The sellers’ market is good news for emerging market borrowers, giving them access to funds at rates once afforded only to “investment grade” issuers. /Reuters Photo

The sellers’ market is good news for emerging market borrowers, giving them access to funds at rates once afforded only to “investment grade” issuers. /Reuters Photo

“We have been more selective in our new issue participation rate for single B credit including Latin American airlines and Chinese real estate,” he said.

Fund managers prefer new issues, particularly on corporate debt or debt issued by countries without a solid repayment history, because they typically sell at a discount to the secondary market. That has not been the case recently, Muaddi said, noting that the percentage of new issues in his fund has dropped from about 20 percent of purchases to 12-15 percent.

Asset managers of dedicated emerging markets funds say the mispricing largely has been caused by “tourist” dollars rushing in from passive funds and non-specialized money managers, such as hedge funds or high-yield funds, chasing higher returns.

“It’s frustrating for me as an investor,” said Josephine Shea, portfolio manager at Standish Mellon Asset Management Company LLC. “There seems to be quite a bit of indiscriminate buying without looking into underlying fundamentals.”

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

Even when they do participate in offerings, some managers say they get less than they want because of high demand. Increasing supply would ease the crunch, but investors say the amounts are already significant for some issuers.

Jim Barrineau, head of emerging markets debt at Schroders, said he has been buying “smaller, less well-known” names and boosting emerging market corporate debt, eschewing stalwarts like Brazil, Mexico and Russia.

While portfolio managers talk of “overcrowding,” many still plan to boost their emerging market debt holdings, expecting inflows to keep recovering after worries about the global effects of the US Federal Reserve’s policy tightening kept investment subdued between 2013 and 2016.

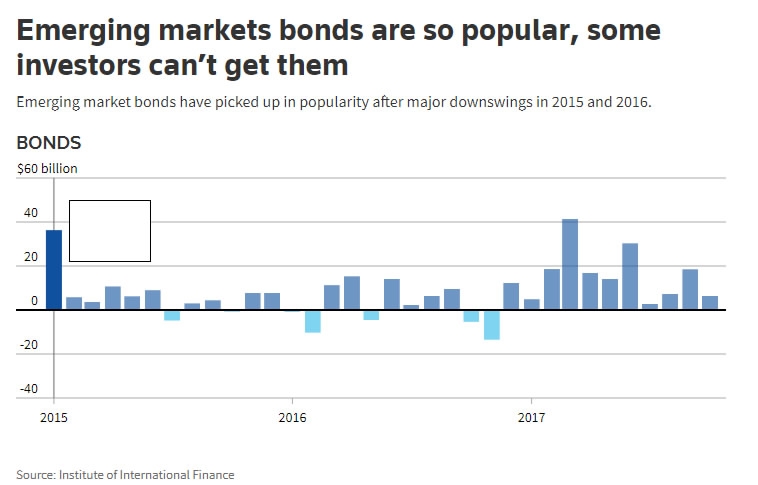

This year, emerging market portfolio debt inflows are seen more than doubling to 242 billion US dollars from 102 billion US dollars in 2016, data from the Institute for International Finance shows.

“Any time you have a market that has had the type of performance that EM debt has had over last 18 months there’s going to be some trepidation, but it’s important to look at fundamentals,” said Arif Joshi, emerging markets debt portfolio manager at Lazard Asset Management.

Source(s): Reuters

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3