Politics

08:35, 27-Mar-2018

Philippines moves to protect migrant workers after young woman abused to death

By Barnaby Lo

September 2016 was the last time Joanna Demafelis’ family heard her voice. A year and a half later, Demafelis came home in a coffin. She had been dead all along. In February, Kuwaiti authorities raided her employers’ apartment over an eviction notice. It was empty except for the body of Demafelis stuffed in a freezer.

The gruesome murder of Demafelis sparked outrage in her native Philippines. Her employers, Nader Essam Assaf, a Lebanese, and his Syrian wife, were arrested in Damascus not long after the discovery of the crime. But President Rodrigo Duterte had wanted more than justice for Demafelis. In February, he ordered a ban on new deployments of Filipino workers to Kuwait, and has been considering enforcing a similar ban to other countries that hire Filipino domestic labor.

Demafelis is not the first Filipino migrant worker to have died at the hands of an employer and under such brutal circumstances. Clarissa dela Cruz, a domestic helper who had just returned from Kuwait, says she may well have ended up dead like Demafelis had she not been able to get someone to upload a video of her employer hitting her on Facebook.

Jessica Demafelis, the sister of Joanna Demafelis who was found dead in a freezer in Kuwait, cries as the wooden casket of her remains arrives at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport, in suburban Pasay city, Philippines, February 16, 2018. /AFP Photo

Jessica Demafelis, the sister of Joanna Demafelis who was found dead in a freezer in Kuwait, cries as the wooden casket of her remains arrives at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport, in suburban Pasay city, Philippines, February 16, 2018. /AFP Photo

“She banged my head against the wall. She hit my leg and pierced my shoulder with a club,” Dela Cruz told CGTN.

For seven months, Dela Cruz says she endured verbal abuse and unimaginable workload. She also claims she was fed very little and was paid less than the salary indicated in her contract.

She says she asked her employers to release her from her contract several times, but they would not.

“Later on I learned from my agent that my employers learned about the video. Apparently, they got scared and decided to let me go,” Dela Cruz said.

For weeks following the revelation of the murder of Demafelis, the Duterte government stood by its labor export ban to Kuwait. A breakthrough came over a week ago, after the two countries struck a draft agreement that would prohibit Kuwaitis from keeping their Filipino household employees’ passports, and from trading them to other employers, according to Kuwait’s state news agency KUNA.

It is not clear, however, when the Philippine government would lift the ban. President Duterte has laid out more demands. He wants, for instance, to be assured that Filipino domestic workers in Kuwait are given at least seven hours of sleep every day, to be fed the right amount of food, and to be allowed to go on holidays.

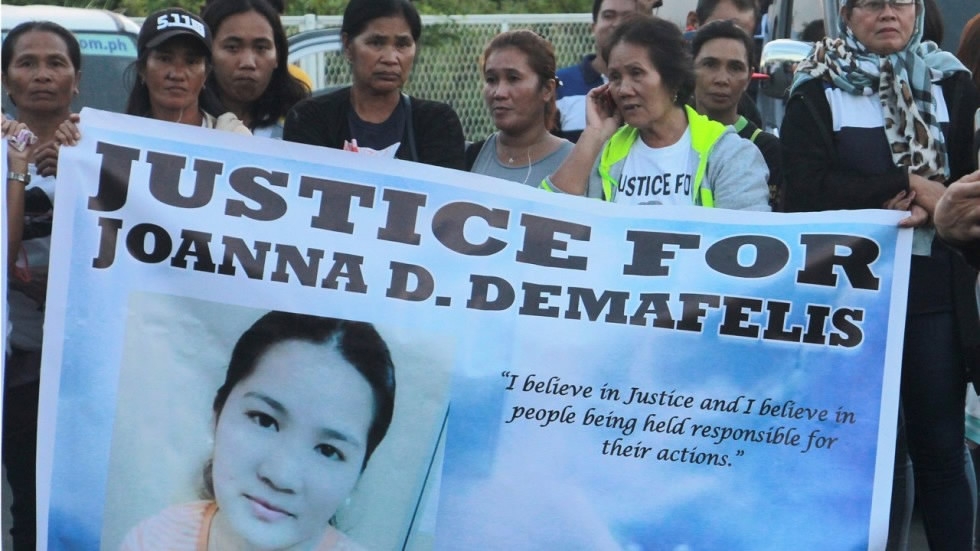

Relatives of Joanna Demafelis hold banners as they wait for the arrival of her body at Iloilo International Airport, February 16, 2018. /AFP Photo

Relatives of Joanna Demafelis hold banners as they wait for the arrival of her body at Iloilo International Airport, February 16, 2018. /AFP Photo

Meanwhile, the Philippine government is working to forge similar arrangements with other countries that hire Filipino workers. Brigido Dulay, deputy administrator of the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration, told CGTN that he had recently come back from a mission to Saudi Arabia, where cases of abuse on migrant workers are also rampant.

Dulay refused to say whether his team found it necessary to recommend a similar ban to Saudi Arabia, but expressed concern over the Kafala sponsorship system in the Middle East.

“It ties down the worker to a certain employer who can grant the entry visa and can also deny the exit visa. So in a sense, the worker is at the mercy of the sponsor,” Dulay said.

Yet as hundreds of overseas Filipino workers in Kuwait have chosen to avail of their government’s offer to bring them home, thousands more are leaving the Philippines each day in search of better opportunities.

3292km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3