Culture

22:50, 23-Nov-2017

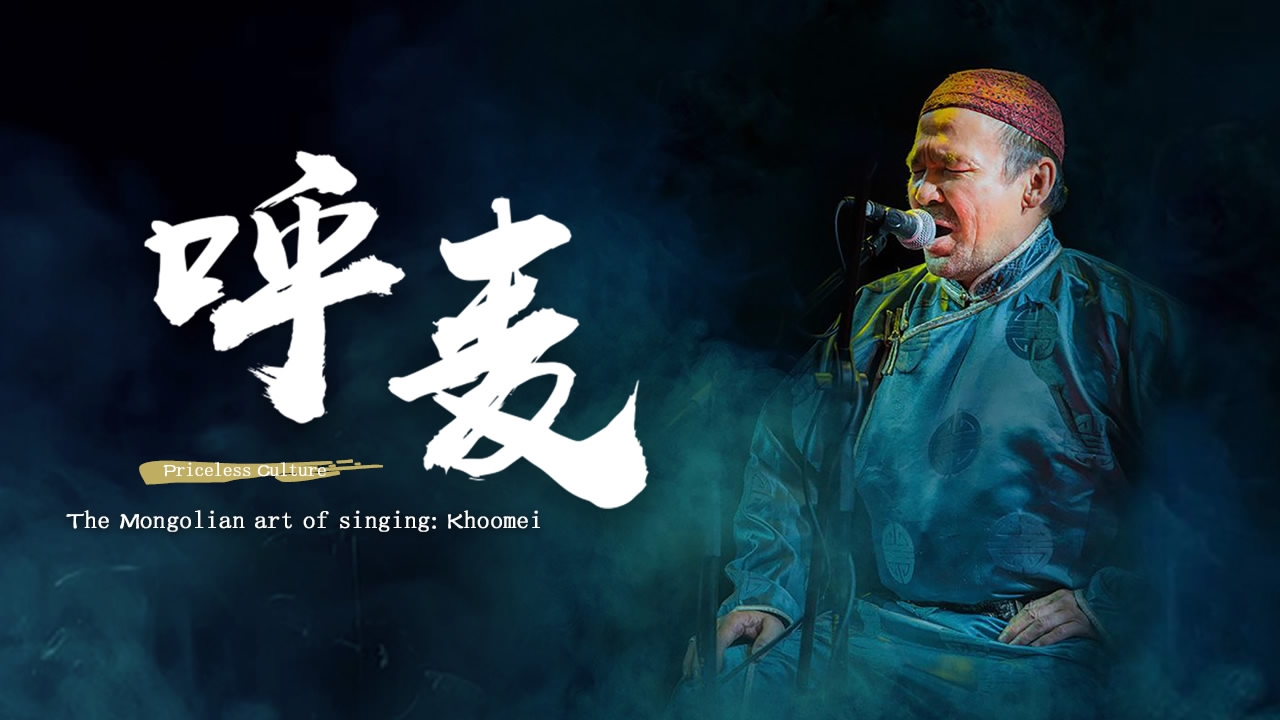

The stirring art of Mongolian throat singing

By Li Jingjing

The capabilities of a human body are sometimes beyond a brain’s imagination.

For example, it’s hard for most people to believe the sound in the video above came from a human being rather than an instrument.

That is because the singer is able to produce a continuous bass and simultaneously produce one or more pitches through his/her throat.

That unique way of singing is known as khoomei, or hooliin chor (throat singing), an art of singing practiced by Mongolian communities in Inner Mongolia in northern China, Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. It is also known as Tuvan throat singing in other cultures.

Through the throat singing band Alash's performance in the video below, you may get a better idea of what this art form sounds like.

It is believed the Khoomei could be traced back to Huns, the nomadic people living between the 4th and 6th centuries in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

Mongolians in ancient times imitated the sound of nature, such as waterfall, forest and animals, during nomadism and hunting as a way of connecting and showing respect to the nature.

This singing art was officially inscribed on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage by the UNESCO in 2009.

Photo via g-photography.net

Photo via g-photography.net

Once endangered

Life styles keep changing. Khoomei, the art that was born in certain geography characteristics and production mode, was on the verge of extinction for a while in history since less people were able to perform.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the art was flourished again along with the more frequent communications with neighboring countries.

57-year-old Hugejiletu, one of the most renowned inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage in China, wasn’t able to perform Khommei at all back in 1996.

Khoomei master Hugejiletu/Photo via China Youth Daily

Khoomei master Hugejiletu/Photo via China Youth Daily

When he traveled to Australia to perform traditional music and instrument for local audience, he was questioned by local reporter how come they didn’t bring Khoomei.

“There were so many of us, yet none could perform Khoomei. I felt ashamed that I couldn’t inherit the culture of my own people,” Hugejiletu told China Youth Daily in 2015.

At the age of 39, he embarked on a tough journey to learn this art. More Khoomei masters from different countries were also invited to Inner Mongolia to help re-boom the culture.

“As a Mongolian, it’s my responsibility to inherit and spread the music and art of our own people,” he said.

As the “living fossil” of Mongolian culture, Khoomei has drawn wide attention from international communities, including musicians, experts of sociology, anthropology and historians.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3