Politics

15:37, 17-Oct-2017

Why Xi's anti-graft drive isn't about political struggle

Dang Zheng

Anti-corruption campaigns are nothing new in China, but the one initiated under Xi Jinping's leadership has arguably run deeper and been more wide-reaching than previous clampdowns.

Some analysts and media outlets have often interpreted the purpose of Xi’s clean-up campaign as a means to strengthen his power base and suppress political opponents.

But public intellectual Robert L. Kuhn argues that this point of view is a superficial and one-dimensional perspective of China and that there are more obvious reasons behind the initiative.

Xi’s government is striving to show respect for the law and judicial impartiality, and the CPC needs to increase public trust and confidence in its continuing leadership, Kuhn argues.

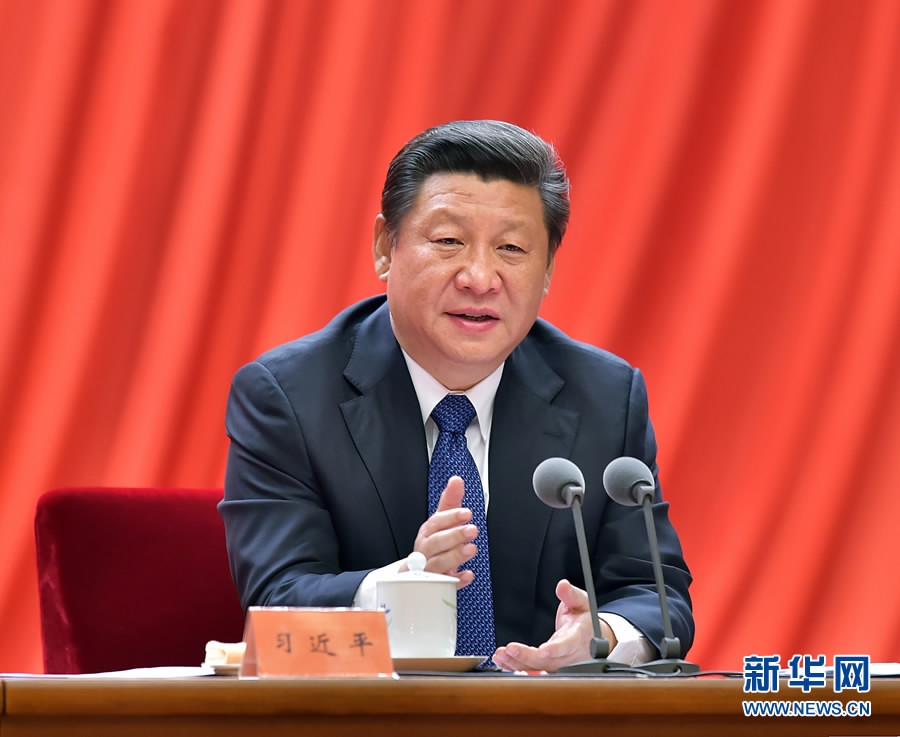

Xinhua Photo

Xinhua Photo

Xi proposed “Four Comprehensives” – to comprehensively build a moderately prosperous society, deepen reform, govern the nation according to the law and strictly govern the Party – a political theory China’s leader unveiled in 2015.

Addressing Communist Party members at a meeting to mark the 95th anniversary of the establishment of the Party last year, Xi said corruption was the single biggest threat to the Party’s continuing leadership and that the anti-corruption drive would continue.

Netting 'tigers' and 'flies'

President Xi vowed to crack down on what he calls “tigers” and “flies” – powerful leaders and lower-ranking bureaucrats – in his campaign against corruption, stressing that no exceptions would be made.

Xinhua Photo

Xinhua Photo

Senior officials of vice-ministerial rank and above have been targeted in an unprecedented clean-up operation.

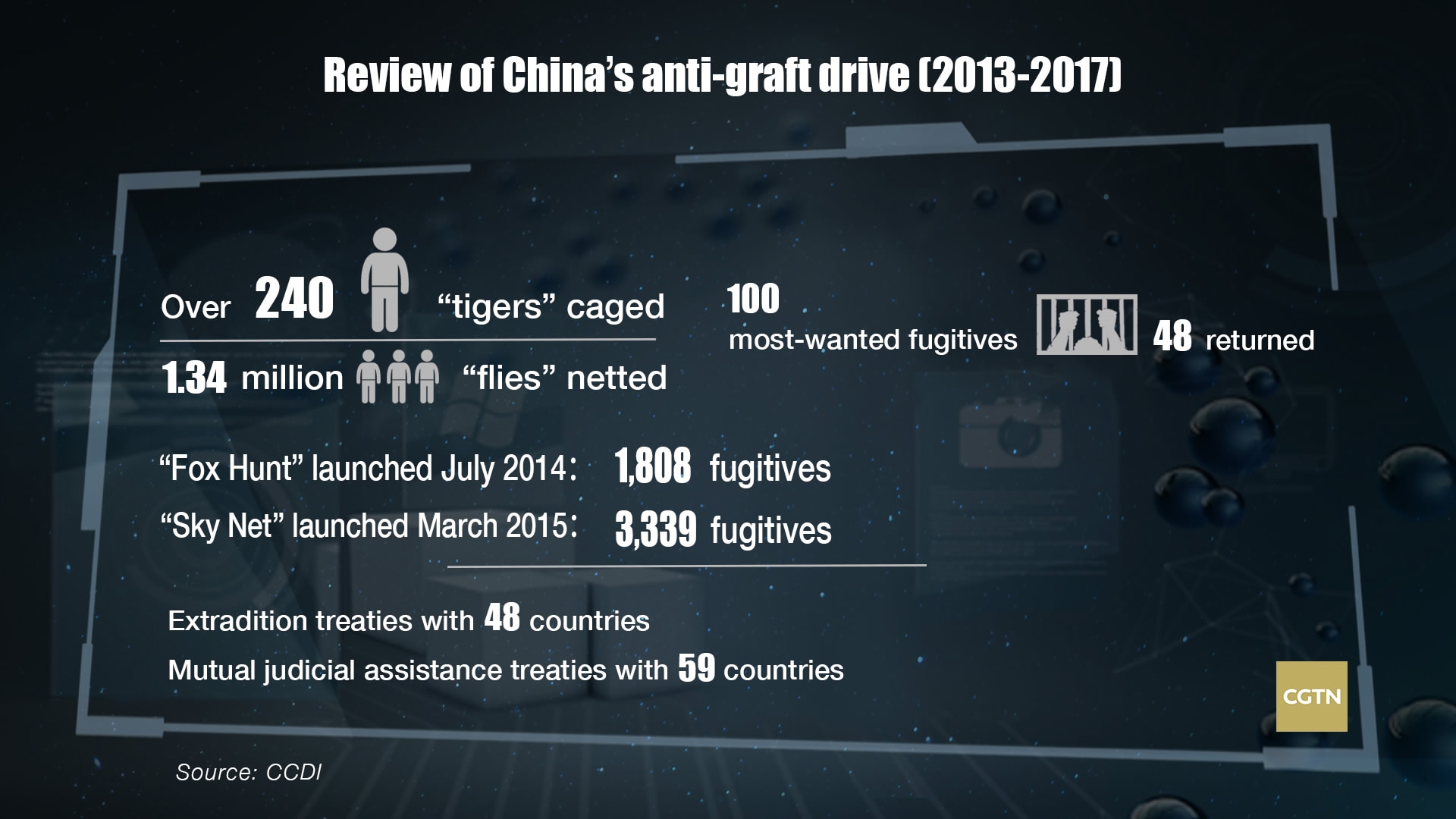

The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), the body tasked with enforcing Party rules and regulations, said that at least 240 high-ranking officials have been investigated since the campaign started.

They include:

- Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo who oversaw China’s security and judicial systems

- Guo Boxiong and Xu Caihou, two former top generals and both vice chairmen of the Central Military Commission

- Ling Jihua and Su Rong, former vice chairmen of China's top political advisory body

- Bo Xilai, former Party chief of Chongqing Municipality

While the charges against Xu were dropped following his death in 2015, the other officials were all sentenced to life imprisonment.

In the meantime, these high-profile cases made headlines around the world, a large proportion of the country’s anti-graft drive has targeted lower-ranking village and county officials.

Roughly 1.34 million lower-ranking officials have been punished since 2013. Those punished for graft include 648,000 village-level officials and most crimes were related to small scale corruption, the CCDI said in October.

No hiding place

The war on graft has also spread beyond China’s borders with overseas searches dubbed Operation “Fox Hunt” and “Sky Net” hunting down officials and business executives who fled China with their assets.

The CCDI launched the annual “Fox Hunt” operation in 2014., with at least 1,808 fugitives returned to China by early this year.

Since the start of the “Sky Net” operation in March 2015, some 3,339 fugitives. including 628 officials, were either returned to China or gave themselves up, with over 9.36 billion yuan seized.

Xinhua Photo

Xinhua Photo

Forty-eight people previously on China’s list of the 100 most-wanted fugitives have since returned home, with many having fled to the United States, Canada or Australia.

Most recently, a court in Hangzhou in east China jailed Yang Xiuzhu, the number one most-wanted fugitive for eight years for graft and taking bribes. She returned to China last year after fleeing to the US in 2003.

In April, the CCDI said it had built a database of the most detailed personal data released on overseas suspects to date.

They have an online platform where the public can provide authorities with tip offs, adding that fugitives have no safe place to hide.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

But cross-border law-enforcement cooperation has met with some resistance, as there have been concerns over whether evidence submitted by China meets the standard for Western courts. There have also been allegations that some extradition requests have been politically motivated.

Addressing these concerns, President Xi said the laws of each country must be respected equally without “double standards.”

China has signed extradition treaties with 48 countries including France and Italy, and signed mutual judicial assistance treaties with 56 countries including the US, Canada and Australia, the CCDI said in June, in a review of three years of work on hunting overseas fugitives.

'Power in the cage'

Xi has vowed to put “power within the cage” regarding regulations and to create an effective mechanism to supervise and govern the behavior and performance of the country’s top officials and party members.

The new rules are applicable to over 89 million CPC members, including the “critical minority” who wield great power and control over the country.

Xinhua Photo

Xinhua Photo

Xi has pushed for stricter rules to govern the behavior of these officials, demanding they be law-abiding and free from corruption.

In 2012, the CCDI laid out the so-called eight-article regulation, a code of conduct that CPC members must abide by.

Over the past five years, the CCDI has sent its inspectors and conducted 12 rounds of inspections, covering all provincial-level CPC organizations, central CPC and government organs, major state-owned enterprises, central financial institutions and centrally-administered universities.

They have dealt with 160,000 cases of violating the Party’s austerity rules and punished 110,000 officials.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3