Business

21:51, 09-Oct-2017

Richard Thaler takes 2017 Nobel prize in economics

By CGTN's Yao Nian

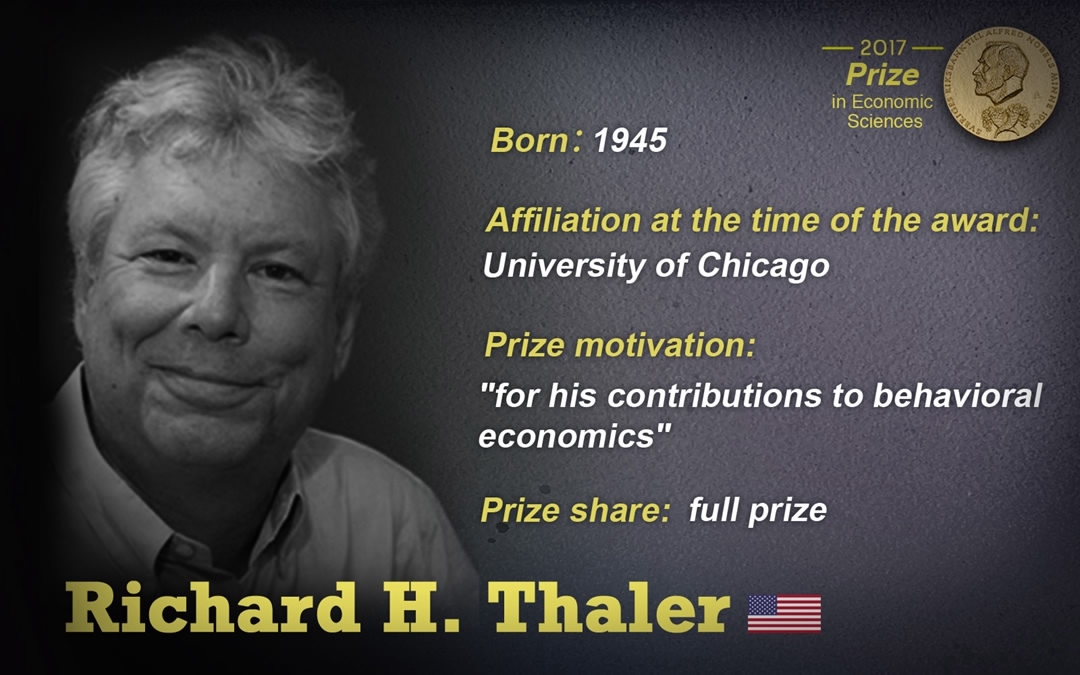

Richard H. Thaler received the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his work in behavioral economics on Monday.

Making economics more 'human'

“I will try to spend it as irrationally as possible!” Thaler said, regarding his prize money.

Thaler, 72, garnered this year’s award for integrating economics with psychology. His theoretical insights show how human traits, such as limited rationality, social preferences and lack of self-control, systematically affect economic decision-making.

“He’s (Thaler) made economics more human,” said Peter Gärdenfors, Member of the Committee, immediately after the announcement.

When people think their New Year’s resolutions can't be kept, or they believe their plans to save for a pension or make healthier lifestyle choices could fail, they could go to Thaler’s best-selling book "Nudge" for help to improve their self-control.

Why would a company choose not to exploit unexpected rain to sell umbrellas for a higher price? Thaler's work shows how consumers’ fairness concerns work in stopping companies from raising prices of goods in high demand.

His research also helps people understand marketing tricks and prevent bad economic decisions.

Thaler is one of the founders of behavioral finance. He received a bachelor’s degree from Case Western Reserve University in 1967 before attending the University of Rochester for a master’s in 1970 and a PhD in 1974. He joined the University of Chicago faculty in 1995.

Click the link for more information about Thaler's work in behavioral economics.

Economics: A Nobel prize newcomer

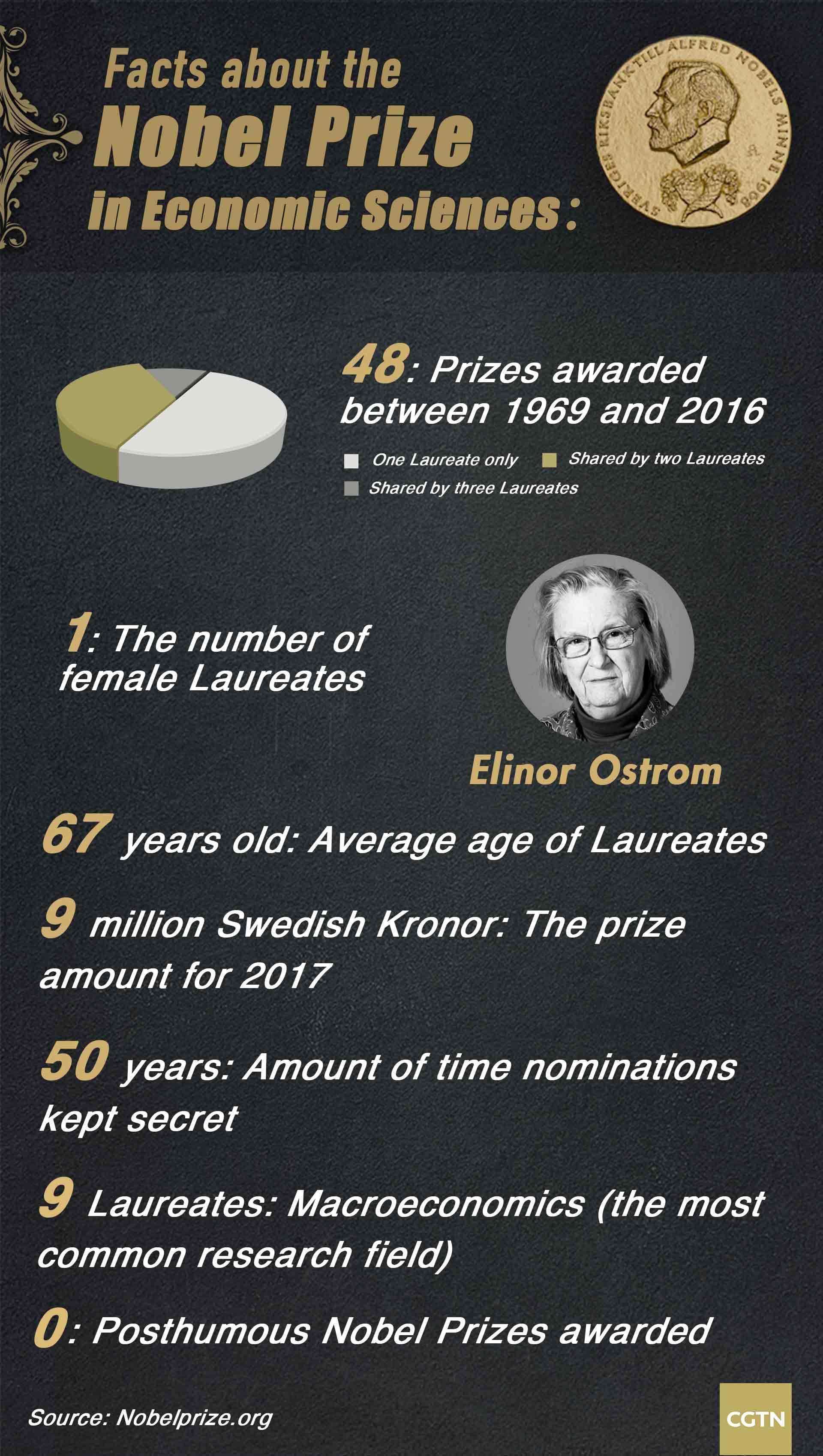

Not among the five original prize categories as specified by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel’s will in 1895, and first awarded in 1901, the Prize in Economic Sciences was founded in 1968 by the Swedish central bank in memory of Nobel, and has been awarded to 78 Laureates since then.

Regardless, the memorial prize is endowed with the same treatment as the original ones. Winners attend the same award ceremony in December to receive a prize medal and a diploma from the Swedish monarch, as well as the same amount of 1.1 million US dollars per full prize.

Nominations are kept secret for 50 years before being screened by the Economic Sciences Prize Committee for selection of the final candidates, who will be recommended to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for selection of the final Laureates.

The prize is not limited to economists, but given to anyone of interest to economics. For example, political scientist Elinor Ostrom received the prize in 2009 for her analysis of economic governance, while psychologist Daniel Kahneman in 2002 was awarded the prize for economic psychology insights.

Past Laureates in economics

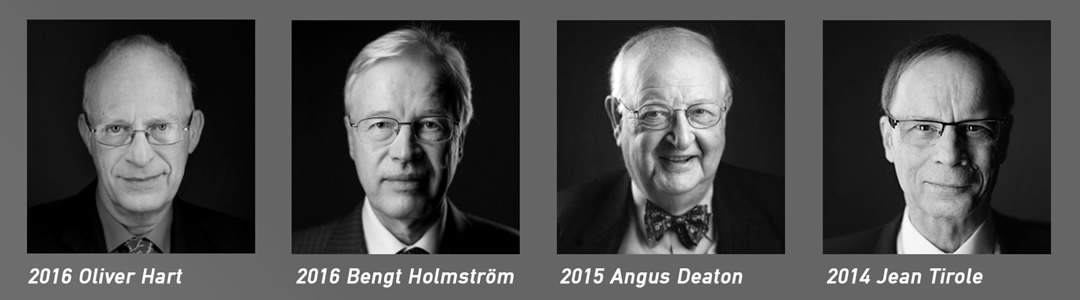

The 2016 Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded jointly to Oliver Hart from Harvard University and Bengt Holmström from Massachusetts Institute of Technology for their contributions to contract theory.

Their analysis can help people understand potential pitfalls in contractual arrangements and the important case of incomplete contracts, which is valuable to optimal contractual design.

The theoretical tools are of great value to modern economies consisting of innumerable contractual relationships, such as those between shareholders and CEOs, or an insurance company and car owners.

Their work can also address a host of questions, such as whether schools and prisons should be privately owned. Their findings also lay an intellectual foundation for bankruptcy legislation and political constitutions.

Angus Deaton from Princeton University was the winner of the prize in 2015 for his analysis of consumption, poverty and welfare.

Deaton’s research links individual consumption choices and society’s aggregate income, which helps design economic policies that promote welfare and reduce poverty.

In 2014, the prize was granted to Jean Tirole from Toulouse 1 Capitole University in France for his analysis of market power and regulation.

With Tirole’s insights, governments can better deal with mergers and cartels, and regulate monopolies in a number of industries, including telecommunications and banking.

6720km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3