Health

19:14, 02-Sep-2017

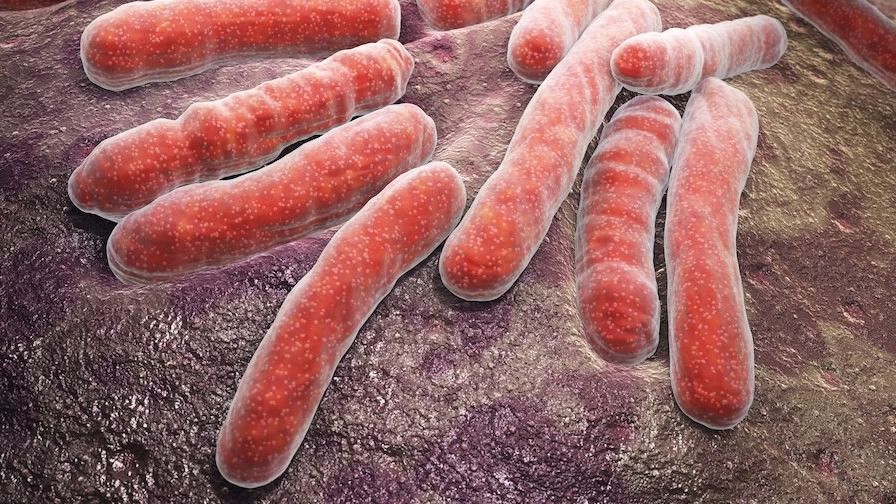

New tool developed to help doctor 'see' bacterial infection in human body

CGTN

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have developed an imaging tool that could help doctors locate and visualize bacterial infections in the body and to rule out other common causes of inflammation.

The research team reported in Scientific Reports that scans made with the imaging technique known as positron emission tomography (PET), detected infections in mice caused by either of the two broad groups of bacteria, gram-negative and gram-positive, without generating a signal from other causes of inflammation.

To perform PET imaging, doctors inject patients with small doses of "radiotracers" that bind to particular proteins or accumulate in tumors, inflamed areas, and other problem spots. The most commonly used tracer, a sugar-like molecule called FDG, accumulates in infected areas, but also follows immune cells to germ-free inflammation sites and tumors.

Photo via Medical Xpress

Photo via Medical Xpress

The treatment for a sterile inflammation is the last thing doctors would want for a patient with an infection.

Other tracers, like radiolabeled antibodies that attach to particular bacteria, could easily miss many infectious strains, and can also emit a stronger signal from dead bacteria, which often have ruptured and spilled their contents, than from intact and live ones.

In researchers' opinions, the ideal molecule would detect only live bacteria, rather than bind to living or dead cells indiscriminately. And it could not be a substance used by human cells, because then every cell in the body would "light up" on a PET scan.

A researcher works in the lab at the UCSF Helen Diller Comprehensive Cancer Center. /UCSF Photo

A researcher works in the lab at the UCSF Helen Diller Comprehensive Cancer Center. /UCSF Photo

One group of molecules that fits the bill was the D-amino acids, which bacteria take up from their environment to build their protective cell walls. These molecules are mirror images of the L-amino acids, which all organisms use to build proteins. But human cells make much smaller use of the D variety.

The team reasoned that a radiolabeled D-amino acid would zero in on bacteria. They settled upon D-methionine, a minor component of the bacterial cell wall that gives a strong signal when radiolabeled. To probe D-methionine's capabilities, they injected infectious bacteria into mice.

When researchers later injected D-methionine molecules tagged with a single radioactive Carbon-11 atom into the mice, PET scanning showed the radiotracer accumulating at both kinds of injection sites.

If D-methionine-based PET imaging was approved for use in humans, it would let doctors find and treat infections much faster. The method could also give greater certainty to doctors when prescribing antibiotics.

Source(s): Xinhua News Agency

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3