Culture

22:33, 14-Feb-2018

Strangers in the cities: A look at the lives of those who build China's cities

CGTN

Li Yanlei has spent most of his winter in what will soon be the tallest skyscraper in Beijing.

Looking down from the top of the 528-meter-high building, Li feels everything below is small and remote.

After arriving in Beijing in August, the then 30-year-old from Henan Province joined the construction of the China Zun tower as a steel worker. He witnessed the completion of the skyscraper’s main structure.

The new Beijing landmark is a symbol of progress and prosperity to many. To Li, it is a reminder of the days and nights spent in atrocious weather high above the ground.

As one of the millions of rural migrant workers in China, Li engages in dangerous and laborious work while struggling to keep his head above water.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) estimates that the number of China’s rural laborers working in cities reached 280 million in 2016, making up over one third of the country’s total workforce.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

Migrant workers are seen as the engine of China’s spectacular economic growth over the last three decades.

The total migrant labor force could have formed 250 cities over the past 30 years, the Financial Times has calculated, with a population of over two million in each.

Yet, Rome was not built in a day.

Migrant workers at construction sites used to working long hours in tough environments, under great physical and mental stress.

This winter in Beijing the temperature dropped to minus 15 degrees Celsius, leaving Li and his co-workers to fight with cold winds while half a kilometer above ground.

Li Yanlei lives beside Beijing's East Railway Station. He and seven other workers stay in a crowded house that is filled with bunk beds.

Li Yanlei. /By CGTN

Li Yanlei. /By CGTN

On top of the beds are the workers’ colorful old quilts. The company provides a radiator because the house has no central heating.

Next to the dormitory is the canteen. When dinner time comes around at 6 p.m. there is a shortage of electricity. The lights go off, so Li and the other workers dine in darkness. Li eats from a steel bowl filled with rice mixed with other foods.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

Sometimes Li brings food, wrapped in a plastic bag, back from the construction site. As he walks on the road, a train passes by, delivering a gust of wind. Li clutches the bag. “The food remains warm as long as I hold it tight enough,” he grins.

On the same village road, a girl squats beside a door, teasing a dog with beautiful golden hair. People walk by leisurely. The winter sun is warm.

Cao Haipeng, 27, came to Beijing at the same time as Li.

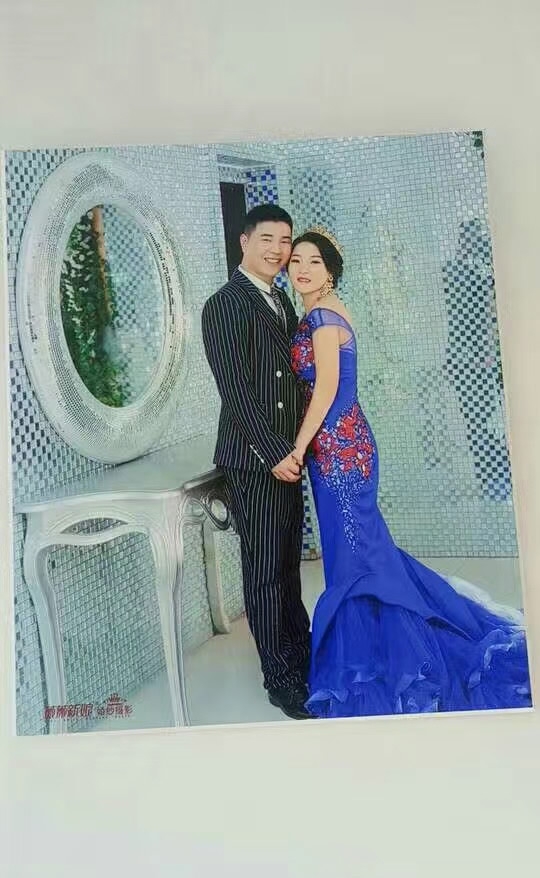

The young man from Inner Mongolia got married in February 2017, and soon after left his wife behind to find work. He too now works in China Zun, installing ventilation pipes.

Cao Haipeng lives with other migrants in a nearby two-bedroom apartment. Unlike Li, they have central heating and steady electricity.

However, after a fire broke out in the city’s Daxing district, killing 19 people on November 18, the Beijing municipal government began clearing safety hazards more strictly in rental housing and apartments. Cao Haipeng and his roommates had to be very cautious.

“We can’t use rice cookers or similar products, and we must shut down all the electricity every time we leave,” the workers grumbled.

Migrant workers have a reputation as “shy and silent” types, but Cao is sociable, optimistic and seldom complains. He is not happy with the food at the building site, however.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

Since the construction sites in the city have no place for workers’ canteens, Cao has to buy lunch boxes and squat on the road to eat with hundreds of other workers.

“I can’t have a warm meal. The food is ice cold when I am halfway through it,” Cao said. “People won’t understand how that feels.”

There are other things the city dwellers cannot understand.

Stories about migrant workers taking off their shoes when entering the subway or not taking empty seats on buses are frequent. But we seldom hear about the vulnerable yet proud hearts behind such anecdotes.

Workers worry their clothes might soil those of others or the seats, one of Cao’s roommates explained.

Although living in populous cities, migrant workers are like isolated islands.

“Sometimes the way they look at you or their unconscious act of dodging you in places like subways or buses makes me feel hurt,” says the roommate.

According to an NBS report, the social integration rate of migrant workers entering cities is low: their main contacts are confined to fellow villagers, co-workers and other migrants. They have little to no contact with people beyond their circle, as well as limited access to public education, healthcare, and other social benefits enjoyed by urbanites.

Since 1958, China has controlled the migration of its citizens with the household registration (hukou) system. Rural migrants have always drifted: in 1953, they were called “mangliu” (blind flow) and, later, migrant workers. They have always been strangers in the cities they help to build.

Cao Haipeng. /By CGTN

Cao Haipeng. /By CGTN

However, strangers still have homes to go back to.

Cao Haopeng doesn't adopt a tone of sadness or self-pity. Instead, he brims with a youthful vitality.

“The clothes we wear at work are dirty, but when we are off work, we wear clean clothes with brands,” said Cao. Every time Cao smiles, his eyes turn into two thin curves. “I would rather spend my money at home, going shopping with my wife and buying clothes!" he says cheerfully.

The “new generation” is changing the image of migrant workers shaped by their parents.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

People born in the 1980s and beyond, like Cao and Li, are considered the third generation of migrants, also known as the “new generation.” Statistics shows that this segment of workers has gradually become the driving force, accounting for nearly half of the total.

This generation has greater freedom than that of their parents. The term “migrant workers” is no longer only associated with words like "hardworking," "poor," or “unfair treatment.”

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

More choices are available. Many of the “new generation” are starting to enjoy life differently and chase dreams.

In some factories in the Yangtze River Delta, the flow of migrant workers is increasing. A worker at a garment factory may dream of becoming a fashion designer, another may have already quit to be a bartender.

Workers are willing to try other ways to make money: small businesses and online shops are two of many options. They are no longer “destined” to be migrant workers. Some are waiting for an opportunity to change their fates.

Instead of building a home as their parents did, some buy apartments in small cities near their hometowns.

Li Yanlei. /By CGTN

Li Yanlei. /By CGTN

Cao Haipeng was married in the city of Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, and purchased an apartment there. The house cost him 400,000 to 500,000 yuan (63,000-78,000 US dollars). He said it was a start.

Cao is also a fan of technology, keen on talking about Jack Ma, big data, AI, and virtual reality. “Using a computer to predict how 300 million netizens will look when they get old, isn’t that crazy?" Cao exclaimed excitedly.

“I don’t read Tencent news. It’s too ‘low’,” he added. He even peppers some English words into his sentences.

Unlike Cao, Li Yanlei is a self-confessed nerd who loves reading and thinking about philosophical questions.

Chinese classics such as Tao Te Ching and the Four Books of Confucianism are all on his reading list.

“I have never gone to college, but I have to know how and what we live for," Li said.

Li talks like a Zen master, but one thing that he cannot be mellow about is his family and children.

Li started work after graduating from junior high school, and has labored in many cities in China. In 2017, with the money he made over the years, he bought an apartment in his hometown.

Li has an eight-year-old son and an 11-month-old daughter. The whole family lives on Li’s 7,500 yuan monthly income, and has more than 10,000 yuan left in mortgage loans.

“After the mortgage pressure is gone, I want to go back home and do something I really like,” Li said.

For new and old generation alike, making money and then going home to reunite with family is the dream of many migrant workers. While the older generation wants to build their own houses in their villages, the new generation typically wants a small apartment in their home cities and to send their children to colleges. That would be the ultimate “turning” of their fate, they say.

Even Li Yanlei gets emotional when talking about family. “As a man in his 30s, we have to do what we are supposed to do – working hard to raise my kids and take good care of my parents. That’s my responsibility.”

Cao Haipeng is already looking forward to starting a family. “I won’t come back to Beijing next year. I’ll bring my wife and go somewhere else; maybe have a kid as soon as we are ready,” he said.

Cao Haipeng and his wife; Photo courtesy of Cao Haipeng.

Cao Haipeng and his wife; Photo courtesy of Cao Haipeng.

The workers say that in megacities like Beijing they normally make 7,000 to 8,000 yuan per month, but those who work really hard or have special skills can earn up to 10,000 – more than some recent college graduates.

Yet they normally live in cheap dormitories provided by their employers and eat by the road to save money for their families thousands of miles away.

A combination of the hukou, apathy directed from others, and the high costs in the city stunt their sense of belonging. Instead, they feel their hometown is the place they should return to.

Home is the final destination, and even a source of faith.

One of the worker tattooed 'I miss you' on his arm. /By CGTN

One of the worker tattooed 'I miss you' on his arm. /By CGTN

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

Having received his wages, Cao is ready to go home for the Spring Festival. Before leaving, he and other workers go to Tiananmen Square to watch the flag-raising ceremony.

“I have been here for a long time but haven’t had the chance to see it,” he said.

When he watched the national flag rise against the Beijing sky, he was touched. “Unspeakable and proud,” Cao said.

Li also looks forward to reuniting with his family, having already purchased his ticket home. However, close to the departure date, the foreman tells him that China Zun needs some workers to stay.

They’ll double the wage, the foreman said.

Li decides to stay.

“I’ll go back home after the Spring Festival.”

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

We salute those who made possible the miracle of China's development. /By CGTN

We salute those who made possible the miracle of China's development. /By CGTN

The story is one in The 1.3 Billion series exploring the diverse lives that make up China.

The story is one in The 1.3 Billion series exploring the diverse lives that make up China.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3