After German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s bitter election victory, not only have right-wing populists indulged in the pleasure derived from her misfortune but also Turkey.

It appears that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan got what he wanted: A defeat for Merkel and all mainstream parties in the September elections.

In the aftermath of the election, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu reminded Germany of "its mistakes."

Merkel would not be able to form a government, Turkey’s Hürriyet Daily News quoted Erdogan as saying.

Erdogan launched his salvo while Merkel was campaigning for her fourth term.

He asked Turks in Germany to vote against her and the other main parties in the country. The leader of Europe’s biggest economy secured a fourth term but lost roughly one million votes to the right-wing populists, who would enter the federal parliament for the first time in decades.

The post-election conundrum has made it difficult for Merkel to form a coalition government and the task may take months. /AFP Photo

The post-election conundrum has made it difficult for Merkel to form a coalition government and the task may take months. /AFP Photo

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) also tasted a bitter defeat after they were reduced to 153 seats from 193 in the current parliament.

Rage against Germany

Erdogan called Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) the enemy of Turkey, urging about 1.2 million voters of Turkish descent to vote out the major political parties in an address to worshipers in August.

He also accused Germany of having anti-Turkish and anti-Muslim sentiments.

Did Turkish voters listen to Erdogan?

He enjoys considerable support among German-Turks as many of them have dual citizenship with voting rights in both Germany and Turkey.

All the German-Turks who have voted for Erdogan did not vote for Merkel, SPD and other mainstream parties, said Dean Baykan, German actor and producer of Turkish origin, speaking from the city of Cologne in western Germany.

“My hairdresser is an Erdogan fan, he didn’t vote under the Turkish president’s influence,” he told CGTN.

Merkel, he said, lost thousands of votes and it may be because of German-Turk voters.

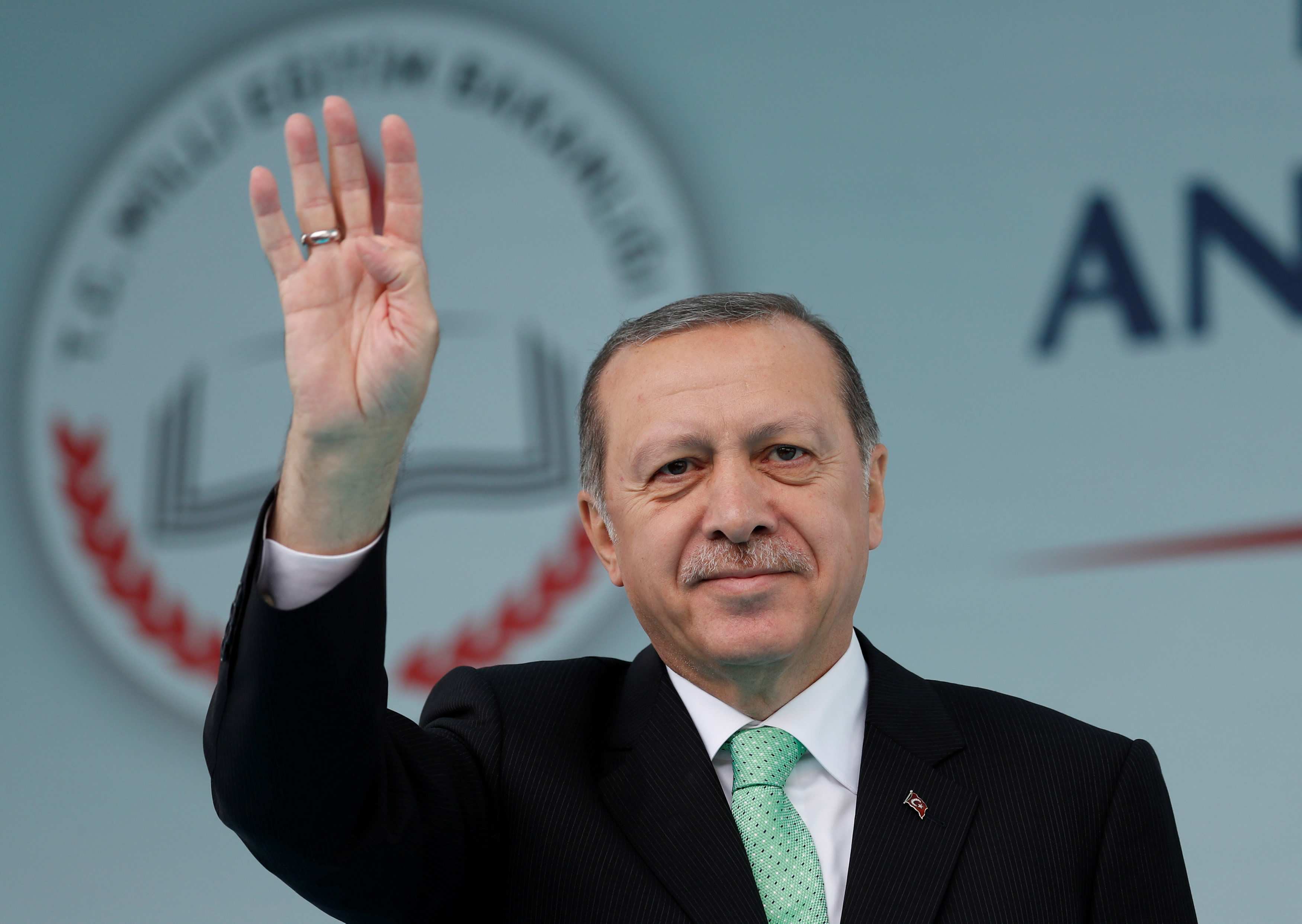

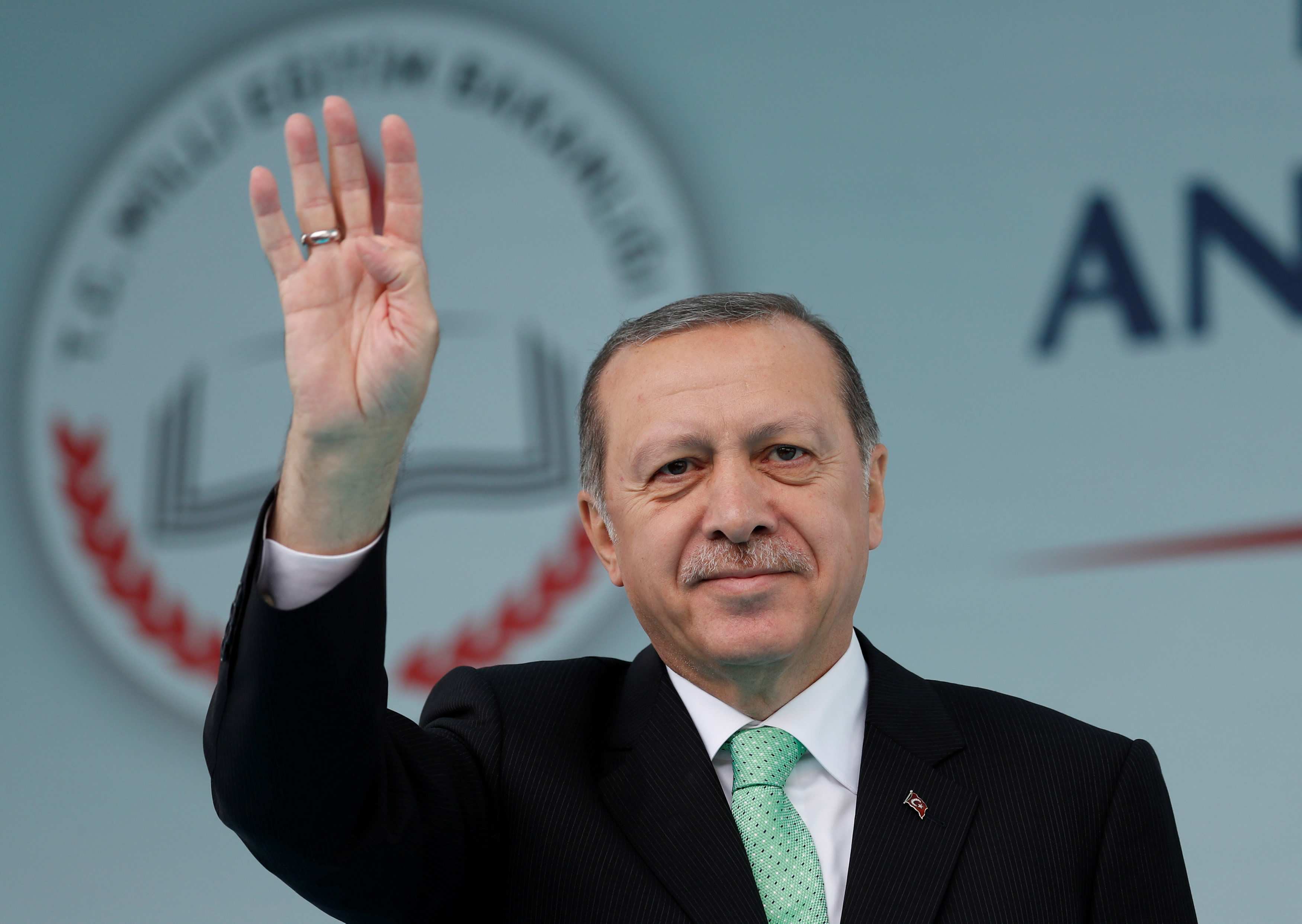

Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan attends opening ceremony of Recep Tayyip Erdogan Imam Hatip School in Istanbul, Turkey, September 29, 2017. Reuters Photo

Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan attends opening ceremony of Recep Tayyip Erdogan Imam Hatip School in Istanbul, Turkey, September 29, 2017. Reuters Photo

“They might have listened to Erdogan. Most of them, not all of them, an estimated 50 percent are pro-Erdogan, it means when he asks them not to do something, they follow,” Baykan explained.

Fierce rebuke

Merkel hit back at Erdogan for ‘interference’ that she said Germany would not tolerate.

Describing the comments as “unprecedented” and meddling with Germany’s sovereignty, foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel called on ethnic Turks to “show those who want to set us against each other that we are not playing their game.”

Community leader Atila Karaborklu blamed Erdogan for wanting to divide Germany’s Turkish community.

Baykan said Erdogan’s interference in German politics was not a good idea.

“No one should interfere in other countries’ politics. It was not right for him to run election campaign in Germany, Angela Merkel did not do so in Turkey,” he said.

Roughly four million Turkish immigrants are living in Germany, where their presence dates back to 1961 when they moved there as ‘guest workers.'

Past trends

Although far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) take the most blame for Merkel’s “nightmare victory," the voting trends from the previous election may provide some insight into the voting choices of German-Turks.

Sixty-four percent of the respondents to a survey conducted by a research institute specializing in immigrant groups, Data4u, said they voted for the SPD in the last election. Twelve percent said they supported the Green Party. The survey was conducted after the 2013 election.

After the disappointing election results, SPD leader Martin Schulz said his party would sit on opposition benches this time. /Reuters Photo

After the disappointing election results, SPD leader Martin Schulz said his party would sit on opposition benches this time. /Reuters Photo

Another study published in November 2016 said that ethnic Turkish have a strong tendency toward the left with some 69.8 percent showing a political connection with the SPD, 13.4 percent with the Greens and 6.1 percent with the CDU.

No such figures reflecting the voting choices of ethnic Turkish Germans about this month’s election are available, but a pre-poll study suggested a change in their political affiliations.

German magazine Der Spiegel quoted the study by the online newspaper Deutsch-Türkisches Journal (DTJ) that hinted at a 15 percent increase since the 2009 election in German-Turks voters who intended to vote in the elections.

Ninety percent of them were expected to vote in the German elections, it said, adding that 43 percent had plans to cast their ballots to the SPD, 22 percent to the Green Party and 20 percent to the CDU.

The survey results were released a few days before Erdogan’s controversial advice to German-Turks, who are considered more conservative. But they don’t traditionally vote for conservative parties like the CDU or its Bavarian sister party Christian Social Union (CSU).

The CDU and CSU oppose Turkey's EU membership bid. They are also against dual citizenship.

Integration and representation

German-Turks have members in parliament, but their participation in society is often questioned.

There are 11 Turkish German MPs in the current federal parliament, of which five are from SPD, three from the Greens, two from the Left Party and one from the CDU. The Greens Chairman Cem Özdemir is also an ethnic Turk.

The leader of Germany's Greens Party Cem Oezdemir cast his vote for the German federal election in Berlin, Germany, September 24, 2017. /Reuters Photo

The leader of Germany's Greens Party Cem Oezdemir cast his vote for the German federal election in Berlin, Germany, September 24, 2017. /Reuters Photo

German-Turks are also blamed for failing to integrate into society. Apparently, it was one of the reasons that made Merkel call German multiculturalism a complete failure.

She said in a speech in 2010 that the attempt to build a multicultural society and to live side by side and to enjoy each other has “utterly failed.”

It appears from “the failure of ethnic Turkish integration” in Germany, that an attempt from a leader, whose roots are in political Islam, to influence their decision about their adopted country shows that German-Turks might be more attached to their Turkish roots than to European values.

A survey conducted by Germany’s University of Münster supported this notion. Titled “Integration and Religion from the viewpoint of the Turkish Germans in Germany,” the study said that nearly half of all ethnic Turks consider following Islamic teaching to be more important than abiding by the law.

Pro-Erdogan politicians have often been holding campaign rallies in Germany with thousands of ethnic Turk Germans in presence. Berlin refused permission for such a gathering in March.

It also said in June that it would be inappropriate for Erdogan to address Turks during the G20 summit held in July.

Diplomatic row

The countries’ relations are at another low point after the failed coup attempt in Turkey in July 2016 that Germany saw as a pretext to quash dissent.

Berlin criticized Turkey for what it called dismantling the rule of law and for the constitutional referendum in April.

The arrest of German human rights activists and journalists in Turkey further damaged ties between the countries.

The Turkish government and many Turkish Germans also took offense after the parliament passed Armenian genocide resolution.

Frauke Petry (2nd R), chairwoman of the anti-immigration party Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD) poses next to Joerg Meuthen (R), leader of the party and top candidates Alice Weidel and Alexander Gauland (L) before a news conference in Berlin, Germany, September 25, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Frauke Petry (2nd R), chairwoman of the anti-immigration party Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD) poses next to Joerg Meuthen (R), leader of the party and top candidates Alice Weidel and Alexander Gauland (L) before a news conference in Berlin, Germany, September 25, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Voters of Russian descent

It was perhaps the weirdest national election in Germany and the worst for Merkel. She faced multiple challenges in the run-up to the elections ranging from the refugee crisis, “Turkish meddling” and rise of the far-right as well as Russian descent voters’ support for the right-wing populists.

The Russian emigrant community helped the AfD to secure first seats in the parliament.

An estimated one-third of party supporters are Germans of Russian descent, totaling five percent of the population, according to the AfD.