Culture

20:44, 04-Oct-2017

Shaanxi Baoji Bronze Museum houses splendid ware: He Zun

By Sun Qingzhao

The He Zun is one of the priceless treasures on show at Baoji Bronze Museum in China’s northwest Province of Shaanxi. It was discovered by chance in 1963 by a local farmer.

It stands 38 centimeters high, and is 28 centimeters in diameter, weighing in at more than 14 kilograms. It was later found that the bronze ware bears the first written form of the name "China."

Housed in the Baoji Bronze Museum in Shaanxi Province, the He Zun bronze ware is one of China’s 64 national treasures that are never allowed to be exhibited abroad.

“A ‘Zun’ is actually a ritual wine vessel, and was placed in the temple. As the drinking vessel is very important in sacrificial rituals, people later used its name to express the meaning of respect,” says Ren Zhoufang, head of the Baoji Bronze Museum Bronze vessels during the Western Zhou Dynasty had different functions. The He Zun was an important vessel, as it was mostly used for sacrificial ceremonies.

It was unearthed accidentally by local farmer Chen Hu in 1963. He discovered the artifact at a cliff near his home one rainy evening.

He Zun Bronze Ware/ Photo courtesy of Baoji Travel Government

He Zun Bronze Ware/ Photo courtesy of Baoji Travel Government

At first sight, the bronze ware startled Chen, as it kept reflecting a green light. He said it made his hairs stand on end. At that time, he had no idea of the artifact's cultural and historical value, and sold it to a waste recycling station.

Chen Hu’s nephew recalls that “at that time, natural disasters had occurred throughout the country, and life was hard. That is why the artifact was sold.”

Luckily, in 1965, the bronze ware was spotted by an employee at the Baoji museum, who brought it back. Ten years later, it was sent to Beijing to be put on display at the Palace Museum.

Before being exhibited, experts removed the rust from the bronze ware, and discovered a 122-word inscription on its base.

The inscription on the He Zun recorded how the city of Luoyang was built by the order of Emperor Zhou Chengwang of the Western Zhou Dynasty, which ran from the 11th century to 771 BC.

Ren Xueli, director of Baoji Bronze Museum talks about its significance, “In Chinese history, there was no written history until the Western Zhou Dynasty. By then, we can see inscriptions that are hundreds of characters long. It is equivalent to the complete archives of the Western Zhou Dynasty, and is important for us to study the history of this dynasty."

Moreover, the expression “Zhong Guo”, meaning the hinterland of China, was used in the inscription for the first time in recorded Chinese history. This further confirmed that the Chinese were already calling their country "China" more than 3,000 years ago.

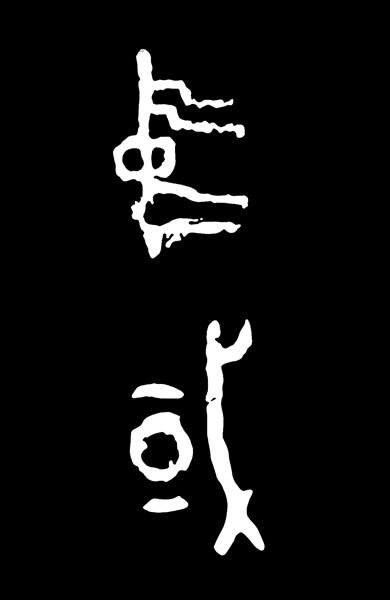

Character 'Zhong Guo' in the inscription/ Photo courtesy of Gansu Provincial Government

Character 'Zhong Guo' in the inscription/ Photo courtesy of Gansu Provincial Government

“The character ‘Zhong’ is written like this: one square and one vertical flag. That is to give people directions. They can see the flagpole far away, making it easier for them to come back home. The written form of the character ‘Guo’ on the inscription does not have the outer frame. It means people at that time thought their country had no boundary.” explained by Ren Zhoufang, head of Baoji Bronze Museum.

Despite all these findings, the He Zun is still shrouded in mystery. People still do not know who the owner of the bronze ware might have been. That is something that needs to be explored further.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3