Business

09:20, 21-Oct-2017

Five years on, is Abenomics still the answer for Japan?

by CGTN's Nicholas Moore

Japan heads to the polls on Sunday, after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called a snap election last month in a bid to bolster power for his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The vote comes after five years of controversy at home and abroad under a leader who has given his name to Abenomics – a divisive set of economic reforms aimed at ending decades of stagnation.

As economists continue to argue whether or not Abenomics has been a success or abject failure, is it time for the policy to come to an end?

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe leaves a lower house hall after the dissolution of the lower house was announced at the Parliament in Tokyo, September 28, 2017. /VCG Photo

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe leaves a lower house hall after the dissolution of the lower house was announced at the Parliament in Tokyo, September 28, 2017. /VCG Photo

What is Abenomics?

The policy follows “three arrows,” which the Japanese government defines as:

1) Aggressive monetary policy

2) Flexible fiscal policy

3) Growth strategy, including structural reform

The logic behind the three arrows was that dramatically devaluing the yen (arrow one) – would boost Japanese exports and manufacturing, which alongside widespread structural reform (arrow three) would boost the economy, inflation, wages and consumer confidence, with the help of economic stimulus and looser fiscal policies (arrow two).

Since becoming PM, Abe has pumped tens of trillions of yen into stimulating the economy and boosting infrastructure. Structural reforms aimed at greater corporate transparency and shareholder responsibility have been gradually introduced in a bid to make “Japan Inc.” more productive, efficient and accountable.

Part of Abenomics involves restructuring and reforming Japan's corporate culture, shareholders' rights and wage growth. /VCG Photo

Part of Abenomics involves restructuring and reforming Japan's corporate culture, shareholders' rights and wage growth. /VCG Photo

Tax reform and bureaucracy cuts have also been introduced, with Abe looking to translate economic growth into wage growth, investment and consumer spending.

Has it worked?

It depends who you’re asking – The Economist calls Abenomics a “disappointment,” the IMF earlier this year said it had “improved economic conditions and engendered structural reforms,” while the Financial Times said in May that “Abenomics has not failed, and it should be sustained, not abandoned.”

On paper, statistics give a mixed picture of its achievements. According to Bloomberg, economists expect inflation to peak at 0.8 percent this year before falling again. It averaged around 0.4 percent in the first half of this year, well short of the 2.0 percent target.

Abe’s five-year tenure has coincided with a sluggish global economy, a rising China and, more recently, increased US protectionism and heightened tensions on the Korean Peninsula. The effects of Japan’s ageing population are already being felt, affecting the labor force.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks was self-inflicted – in 2014 the government raised consumption tax from five percent to eight percent in a bid to balance its books (government debt stands at 239 percent of GDP, worse than Greece at 181 percent). The result was a steep economic downturn over two quarters.

However, the Bank of Japan’s latest Tankan survey showed both manufacturing and business conditions are at a 10-year-high, and the overall Tankan index for all industries and companies of all sizes is at its highest point since 1991. With unemployment down to 2.8 percent, current conditions indicate that Abenomics is perhaps finally on track.

What has Abenomics meant for China?

Japan’s political stance on the Diaoyu Islands, its wartime aggression and bolstering its military has meant political ties with China have been tense under Abe, and business ties have been up and down as a result.

The strengthening yuan and Abe’s efforts to control the yen have seen record numbers of Chinese tourists visiting Japan – as of September, 5.56 million tourists from China had spent 543.2 billion yen (4.8 billion US dollars) this year, according to the Japan Tourism Agency.

A tour guide speaks to Chinese tourists in the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Japan, on Sunday, Jan. 22, 2017. /VCG Photo

A tour guide speaks to Chinese tourists in the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Japan, on Sunday, Jan. 22, 2017. /VCG Photo

Japanese customs data released on Thursday showed exports to China surged 29 percent year-on-year in September, on the back of strong shipments of cars, car parts and machinery.

The Japan External Trade Organization found that as of October 2016, there were more than 32,000 Japanese firms in China, and 80 percent of them were turning in a profit.

Lessons for China

Abenomics and Japan’s economic difficulties also provide China with vital lessons for its own future – Beijing should do all it can to avoid falling into the “middle-income trap” of stagnant growth by carrying out and continuing with its own ongoing reforms, while keeping an eye on how Japan copes with its ageing population crisis, a phenomenon that China is looking to avoid.

Japan went through its own economic boom in the 1970s and 80s, and is arguably now paying the price for complacency during that period. This is a lesson that China’s officials are already paying attention to. On Wednesday at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, People’s Bank of China Governor Zhou Xiaochuan warned “if we are too optimistic when things go smoothly, tensions build up, which could lead to a sharp correction…. That’s what we should particularly defend against.”

The future of Abenomics

The snap election on Sunday is, according to polls, likely to see Shinzo Abe cement and even grow his majority in the Diet, meaning Abenomics will continue. The Financial Times quotes chief economist at UBS James Malcolm as saying “what Japan needs more than anything is nothing.” In other words, Abenomics still needs more time, without any sudden jolts or policy changes.

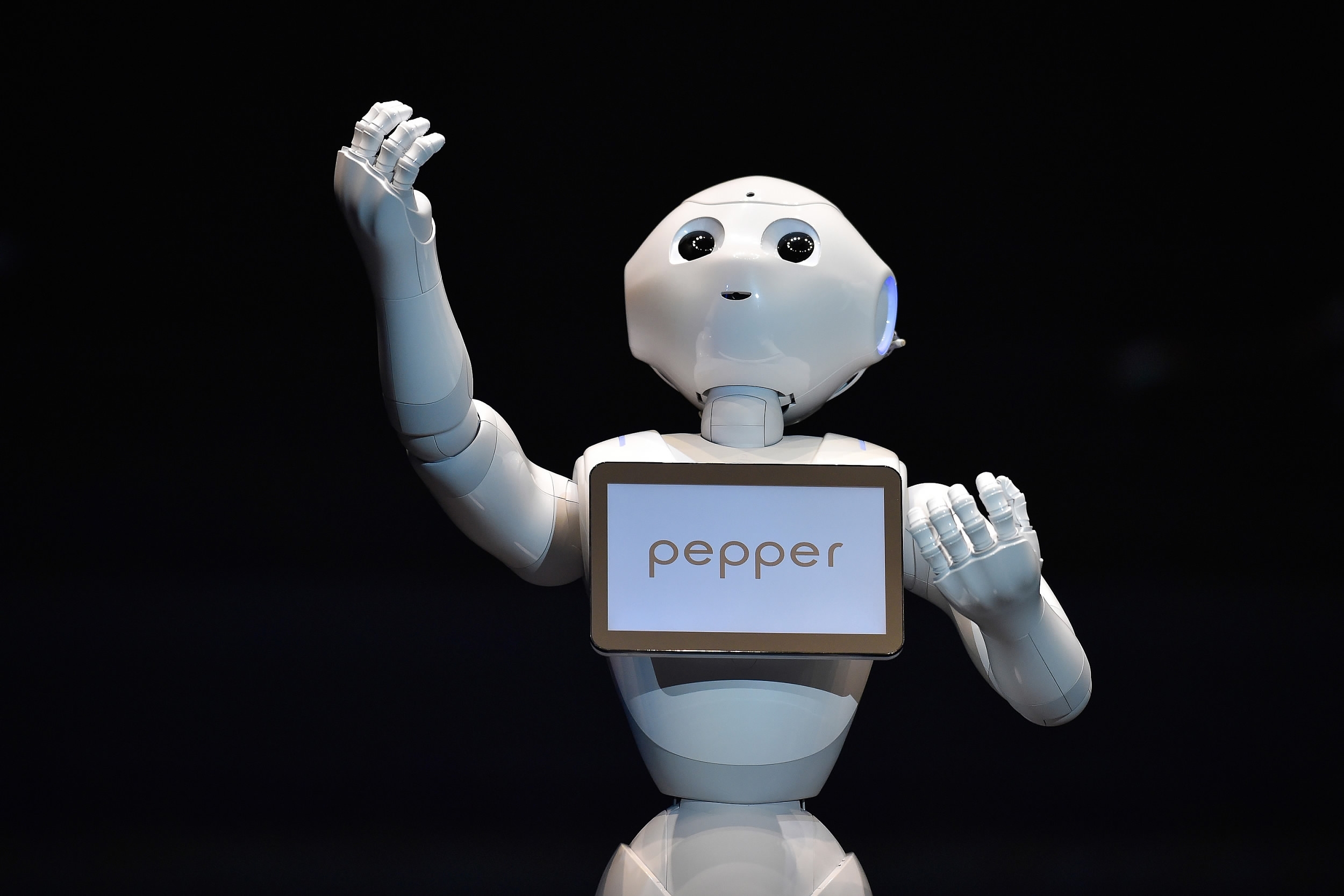

Japan's economy needs a workforce capable of continuing to advance in innovation and technology. /VCG Photo

Japan's economy needs a workforce capable of continuing to advance in innovation and technology. /VCG Photo

Having the freedom to do “nothing” is however wishful thinking, in an increasingly globalized world. Amid increasing protectionism in the US, Abe knows that he needs to forge closer relationships with China – this explains his interest in engaging with the Belt and Road Initiative, expressed at the G20 summit in Hamburg this year.

China also seeks closer ties with Japan, despite ongoing political differences. In September Chinese Vice President Li Yuanchao said, “China hopes Japan can work with China to inject more impetus into the development of bilateral ties.” With the onus on Abe to do more to improve ties with Beijing, another term in office after Sunday’s election could see economic ties finally reach their full potential.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3