Politics

12:58, 09-Dec-2017

Australian think tank denies foreign funding allegations

By Greg Navarro

The deputy director of the University of Sydney Technology’s Australia China Relations Institute James Laurenceson is adamant about his think-tank’s source of funding.

“We’re funded by the University of Sydney Technology, an Australian university,” he said. “My salary is paid for by UTS, I’m on contract with UTS, I’m certainly not funded by any Chinese government body or any Chinese company.”

But the institute is caught in the crosshairs of the Australian government’s proposed laws to crack down on foreign influence and interference. Laurenceson, however, said a wealthy Chinese businessman partly funded the institute when it was established in in 2014.

“The reality is that we don’t receive funding by the source anymore. We are funded by UTS and yet, we are still caught up in all of this,” said Laurenceson.

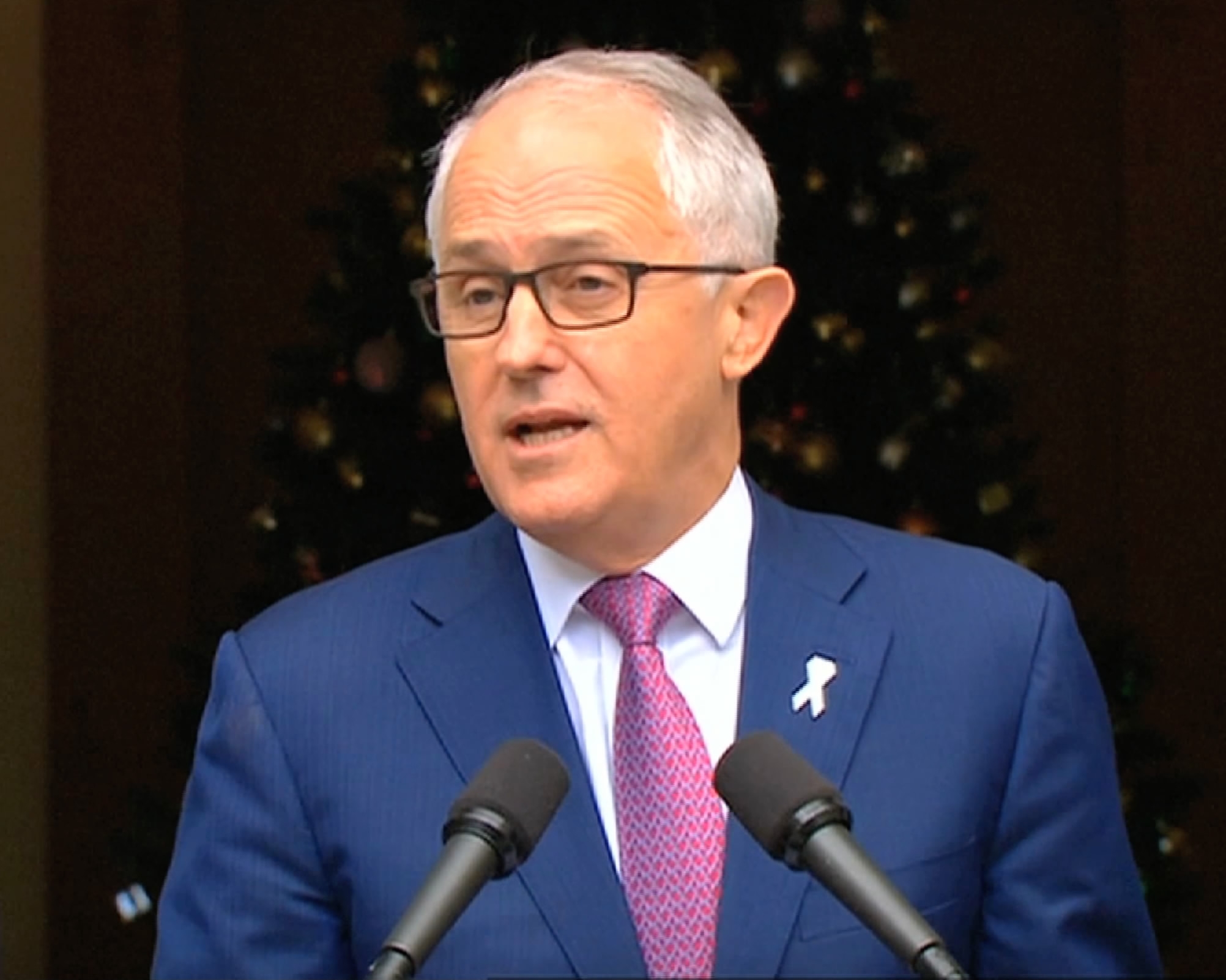

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull /Reuters Photo

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull /Reuters Photo

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said the prosed laws would include a ban on foreign political donations to prevent external interference in domestic politics.

"We must ensure that our politics and our parliament is strong enough to withstand attempts by foreign powers to interfere or influence it,” said Turnbull. “And we should not be naive about this. Foreign powers are making unprecedented and increasingly sophisticated attempts to influence the political process both here and abroad.”

While Turnbull said the laws weren’t aimed at any one country, he did mention Australia’s largest trading partner.

"Now we have recently seen disturbing reports about Chinese influence. I take those reports as do my colleagues, very seriously," said Turnbull.

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang /Reuters Photo

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang /Reuters Photo

That prompted a response by China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang.

"China has no intention of interfering with Australia's internal affairs,” he said, “and has no intentions of using political funds to influence Australia's internal affairs.”

Australian Senator Sam Dastyari /AP Photo

Australian Senator Sam Dastyari /AP Photo

The legislation was unveiled a week after labor senator Sam Dastyari was sacked as deputy whip after news reports linked Dastyari to his interactions with a Chinese businessman.

"So Dastyari is really, if you like, the catalyst, the fall guy for the whole episode," said University of Sydney lecturer Stewart Jackson. “It’s an attempt to wedge the labor party, so it is an attempt to say the labor party has done something wrong therefore, the electorate should be aware of it.”

Australia’s proposed laws are modeled after similar legislation in the US and would criminalize foreign interference. They would also require lobbyists to register when working for foreign companies.

Australian Attorney General George Brandis said that certain groups, such as the University of Sydney Technology’s Australia China Relations Institute, could also have to register.

"We have learned that there are many varieties of foreign interference in the Australian political system'” said Brandis.

Laurenceson is skeptical.

"We had some initial funding from one of the gentleman who has been the focus of this tilt in Australia over the last 12 months towards being quite concerned or skeptical, or even fearful of China, but the reality is we don’t receive funding form that source anymore, we are funded by UTS and yet we are still caught up in this, and that is why this makes me think that this is not such a cut and dried issue - I think it is probably directed at the China ties a bit more generally," he said.

Brisbane, Australia. /Reuters Photo

Brisbane, Australia. /Reuters Photo

The economic ties between the two countries are very hugely important to Australia. The two-way trade in 2016 topped 117 billion US dollars.

"For the most part, for any foreign nation or foreign company you don’t get good value for money in Australia for trying to buy politicians. You get good value for money as importers, as exporters, as foreign investors, as sources of capital," said University of New South Wales Economist Tim Harcourt.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3