Speculation is rife about the nature of the military action the US has said it will mount in response to the alleged chemical attack on the Syrian town of Douma.

US President Donald Trump has warned there would be a "big price to pay" in the wake of the April 7 attack, and in recent days he and his allies have ramped up their threats of military reprisal.

Washington blames the government of President Bashar al-Assad and Russia over the purported chemical weapons assault, but both Damascus and Moscow deny the accusations.

White House spokeswoman Sarah Sanders insisted on Wednesday night that no specific plans have been laid out yet, in what appeared to be a reversal of Trump's earlier tweet warning of "nice and new and 'smart'" missiles coming Syria's way.

The rubble of damaged buildings in the town of Douma, eastern Ghouta, in Damascus, Syria, March 30, 2018. /Reuters Photo

The rubble of damaged buildings in the town of Douma, eastern Ghouta, in Damascus, Syria, March 30, 2018. /Reuters Photo

Despite the scope of the military retribution being under debate, there is little doubt among experts that a military strike would target strategic facilities in Syria.

What in the war-torn country might be within the range of Western missiles?

Military airfields

The US said it had evidence that the suspected nerve agent was sprayed from helicopters, unleashing a torrent of speculation as to which airfields could be targeted. Some however questioned whether striking runways, usually used by fighter jets, would prevent helicopter attacks in the future.

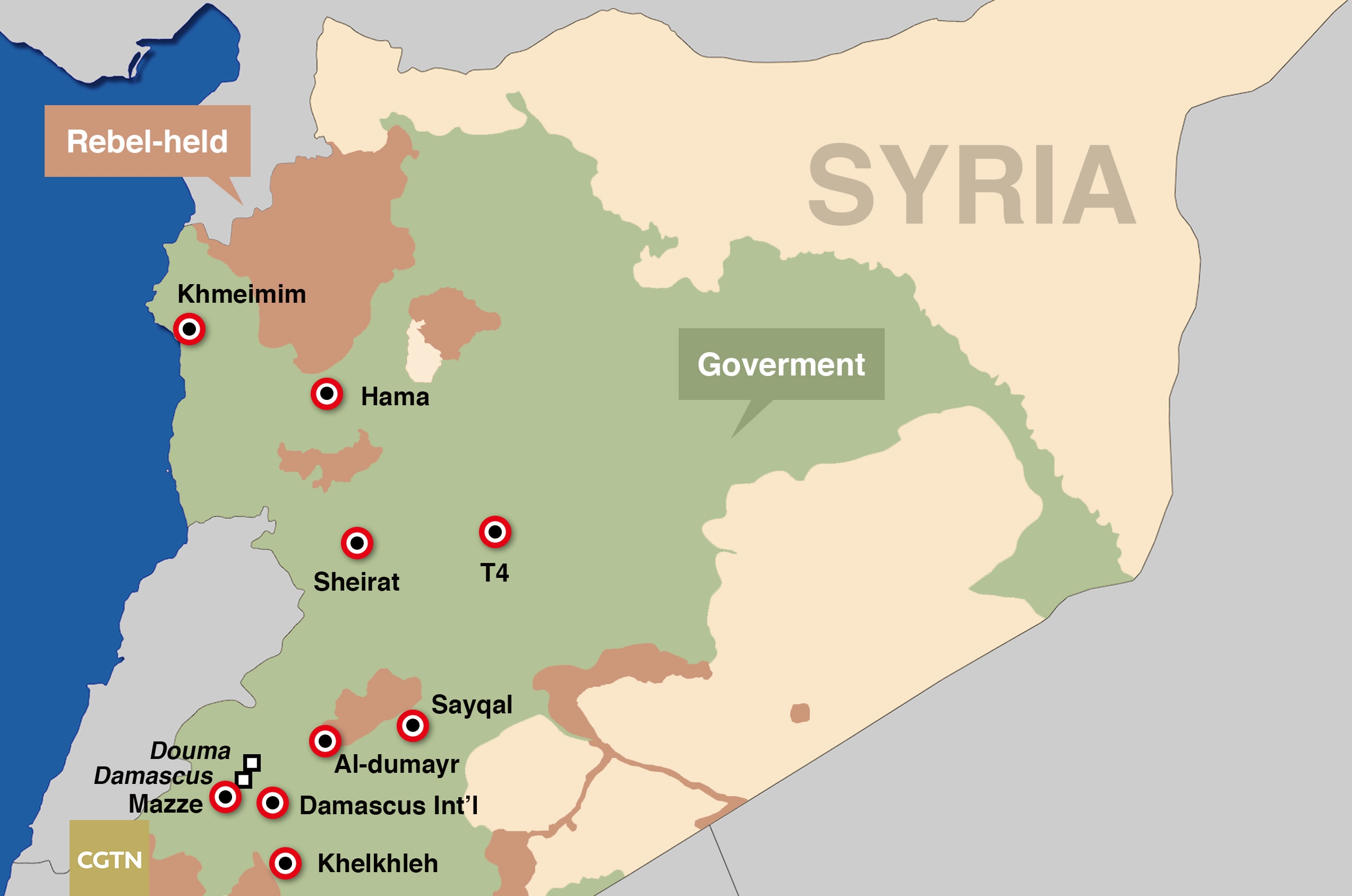

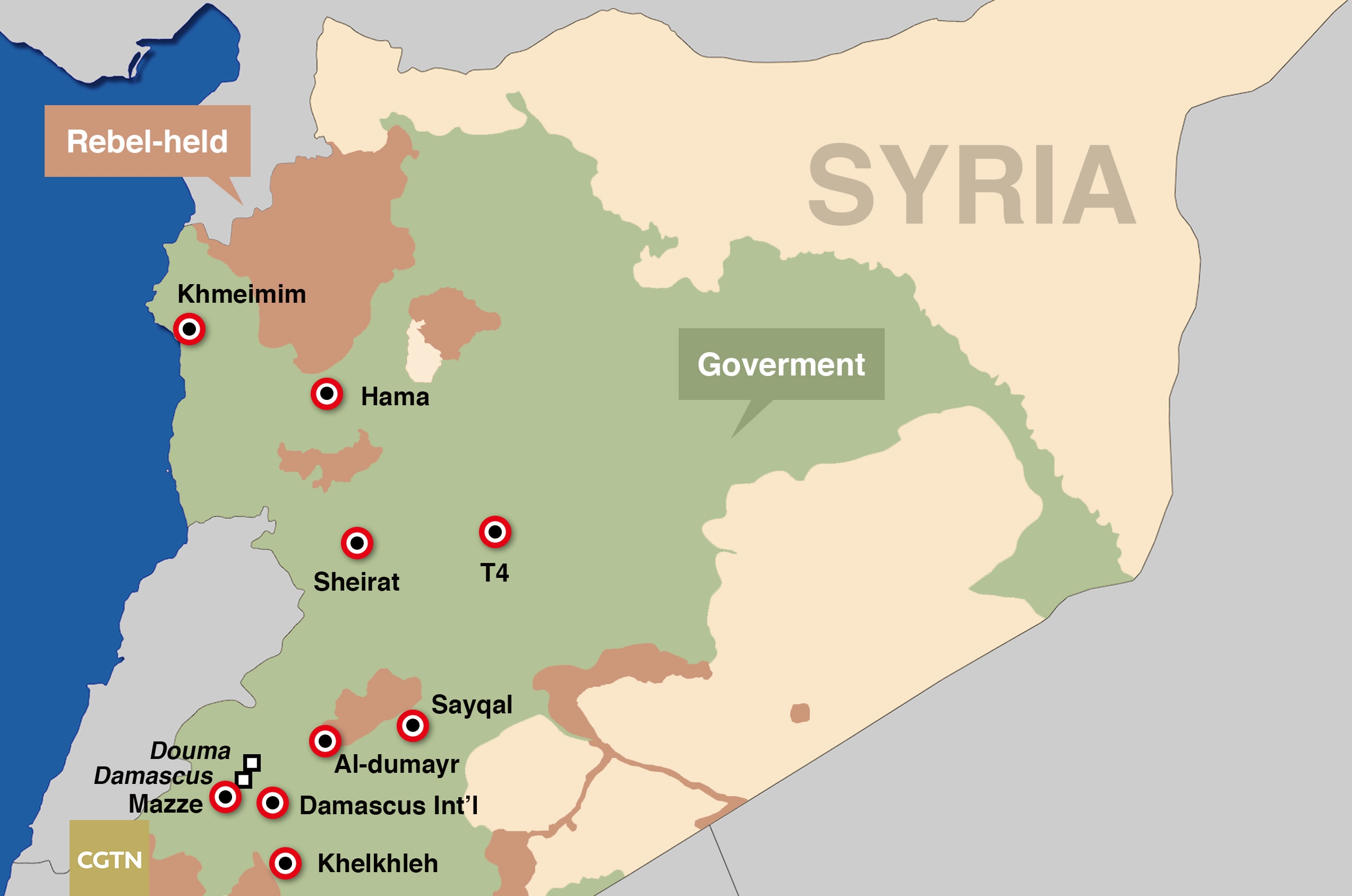

Map showing a number of government-controlled military airports and air bases in Syria.

Map showing a number of government-controlled military airports and air bases in Syria.

Last April, following a deadly sarin attack in Khan Sheikhoun, northwestern Idlib province, also blamed on the government forces, Trump ordered the US' first and hitherto only missile attack in Syria. It struck Shayrat airbase in the central province of Homs, from where the jets suspected of releasing the poisonous agent were thought to have taken off.

On Monday, the T-4 airbase, also in Homs, was targeted in an attack initially blamed on the US, then Israel.

Qatari-owned publication New Arab quoted on Wednesday Col Mustafa Bakour, a defector from the Syrian government forces, as saying there are five military airports from where the country's air force launches "the most violent" strikes.

These military facilities, mostly located in the central and western parts of the country, are Shayrat airport (Homs), Hama airport (Hama), T-4 airport (Homs), al-Dumayr airport (outskirts of Damascus) and Saiqal airport (Damascus).

Russian and Syrian servicemen line up near military jets at Hmeymim airbase, Syria, March 15, 2016. /Reuters Photo

Russian and Syrian servicemen line up near military jets at Hmeymim airbase, Syria, March 15, 2016. /Reuters Photo

However, the Syrian government's reported attempts to relocate its air assets, probably somewhere shielded by Russian military hardware, might cause the US to reconsider its options in order to avoid direct confrontation with Moscow.

Research centers

The Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Center (SSRC), a government agency overseeing various scientific activities, might also come under fire, according to analysts, because of their alleged role in producing chemical munitions used by government forces.

Under an agreement brokered by the US and Russia in 2013, the Syrian government destroyed its stockpile of chemical weapons, with the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) overseeing the process.

The OPCW says Damascus has been complying with the deal, but a slew of attacks with chemical agents have been blamed on the Syrian government.

According to the Washington-based Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control, the Syrian government is believed to have carried out at least 29 chemical weapons attacks since 2013. Syrian authorities have repeatedly decried such allegations.

A rocket is launched by the Syrian army in eastern Ghouta, Syria, April 7, 2018. /Xinhua Photo

A rocket is launched by the Syrian army in eastern Ghouta, Syria, April 7, 2018. /Xinhua Photo

Media reports and intelligence documents have claimed that the SSRC is still engaged in the manufacturing of toxic agents in violation of the 2003 deal.

An intelligence document by a "Western intelligence" obtained by the BBC in 2017 pointed at three sites – all branches of the SSRC – where prohibited weapons are produced and maintained, namely in Masyaf, Hama province, and Barzeh and Jamraya, on the outskirts of the capital Damascus. The latter was struck by what were thought to be Israeli jets before last December.

Michael Eisenstadt, director of the Military and Security Studies Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, urged the US earlier this week to target Syrian chemical weapons infrastructure "when collateral damage can be minimized," while focusing on the government's conventional military capabilities.

Skeptics have wondered however why the US, if indeed it had the coordinates of where Syria's alleged chemicals are produced, has refrained from striking them earlier. Questions about whether centers allegedly manufacturing chemical agents are the same as storage facilities and the consequences of missile attacks targeting such establishments on the environment also linger.

Leadership centers

Some experts believe that the US and its allies could launch a broader military action plan to hit the Syrian government where it hurts the most – the leadership. Command and control centers, as well as intelligence headquarters, could be on the potential hit list, some have argued.

"It is also possible [for the US] to target the presidential palaces of the Syrian President," Daniel Serwer, a scholar at the Middle East Institute, told Deutsche Welle.

The Presidential Palace, the primary residence of Assad, is located west of the Syrian capital on Mount Mezzeh. Syria's first family also have another residence, Tishreen Palace, also in Damascus, which has been previously bombed.

The Presidential Palace in Damascus /Flickr Photo via The Guardian

The Presidential Palace in Damascus /Flickr Photo via The Guardian

"Such military strikes could lead to the death of the Syrian president, and in this case he will be a legitimate military target him being the supreme commander of the Syrian army," Serwer noted, adding that it is unlikely Washington goes down that road as it will be unable to deal with the fallout of such action in light of lack of Assad's alternative.

Syrian air forces' intelligence services, headquartered in the Mezzeh neighborhood near the capital, could also be a potential target. Another possible aim could be the Mezzeh Military Airport, which houses the 4th Armored Division and the Republican Guard, under the command of the president's brother Maher al-Assad. The facility was targeted before in December 2016 and January 2017.

Calculated or just random?

Details of what exactly happened in Douma last Saturday remain murky amid conflicting reports as to who did what, and absence of a probe by neutral investigators.

The ambiguity of the situation on the ground and lack of ironclad proof as to who should be held accountable have put into question whether the military retaliation against the Syrian government is warranted and if so, the likelihood of it achieving its desired effects.

Trump has built its case against the Assad government at a time when the US intelligence is still assessing the situation.

A still from a video, documenting a child cries as they have his face wiped following an alleged chemical weapons attack in what is said to be Douma, Syria, April 8, 2018. /Reuters Photo

A still from a video, documenting a child cries as they have his face wiped following an alleged chemical weapons attack in what is said to be Douma, Syria, April 8, 2018. /Reuters Photo

Asked if he had seen enough evidence to blame Assad, US Defense Secretary James Mattis was quoted by Reuters as saying, "We’re still working on this."

The news agency also reported that the US does not have rigid evidence of the type of the nerve agent allegedly used in Syria and its origin, citing two unnamed government sources.

Meanwhile, Syrian and Russian authorities have vehemently denied any involvement in the purported attack, with Moscow dismissing the accusations as "fabrications" and going as far as questioning whether the incident ever happened.

A World Health Organization report on Wednesday, which revealed that around 500 people had shown "signs and symptoms consistent with exposure to toxic chemicals," was also disputed by the Syrian authorities, which said it contained "baseless allegations."

"For all the furor about the proposed missile strike on Syrian forces – likely to happen in the very near future – it is difficult to see what it will achieve other than as a general sign of international disapproval of the use of chemical weapons," wrote Patrick Cockburn in The Independent, noting that if dealing a blow to Assad is the intention behind the move, "The time for this is long past, if it was ever there."

(With input from agencies)