Tuesday marked the 106th anniversary of the Wuchang Uprising, which kicked off China's 1911 Revolution that brought an end to the country's last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Among many causes to the revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution, experts have highlighted widespread disappointment and anger among the public at the imperial rulers' refusal to embark on real reforms as the most important reason for the sudden collapse of the 267-year-old empire.

Puyi (L), China's last emperor, and his father Prince Regent Zaifeng /Xinhua Photo

Puyi (L), China's last emperor, and his father Prince Regent Zaifeng /Xinhua Photo

Fall of the mighty

The Qing rulers were under enormous pressure to reform China's political, social and economic systems at the beginning of the 20th century, after repeated humiliation against Western powers and Japan on the battlefield as well as nationwide economic difficulties. Growing Western influence among intellectuals also led to louder calls for change.

In 1908, the Qing court promulgated the "Outline of Imperial Constitution," promising to establish a constitutional monarchy country. However, the document stipulated that the Qing Emperor would rule the empire forever and enjoy supreme authority and privileges. Unwilling to give up power, the imperial rulers turned a deaf ear to several waves of public petitions to open a national assembly.

When the Qing government finally set up a cabinet with Prince Qing as prime minister in May 1911, it made matters worse: Among the 13 members of the cabinet, dubbed the "imperial cabinet," eight were Manchus – the ruling ethnic minority, including five from the imperial clan; one were Mongolian; only four were Han Chinese – the largest ethnic group in China. Even some officials and intellectuals previously supporting the monarchy were infuriated and convinced that a revolution was inevitable, realizing the imperial court's lack of sincerity to carry out political reforms.

Members of the "imperial cabinet" in 1911 of China's Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) /Xinhua Photo

Members of the "imperial cabinet" in 1911 of China's Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) /Xinhua Photo

Shortly after the Wuchang Uprising in today's Wuhan, capital of Hubei Province in central China, 15 provinces declared independence within a few weeks. With the abdication of China's last emperor on February 12, 1912, the country's over 2,000-year imperial rule came to an end.

Race between reform and revolution

Lei Yi, a researcher at the Institute of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said the Qing rulers' unwillingness to alleviate the country's crises through reforms turned its former allies – the traditionally moderate gentry and businessmen – into its enemies. Clinging to their imperial power and resisting calls for reform, the rulers lose the race between reform and revolution, he added.

"History has proven that the most effective way for the rulers to neutralize the 'radicals' is to initiate reform," Lei wrote in a journal focusing on China's reform.

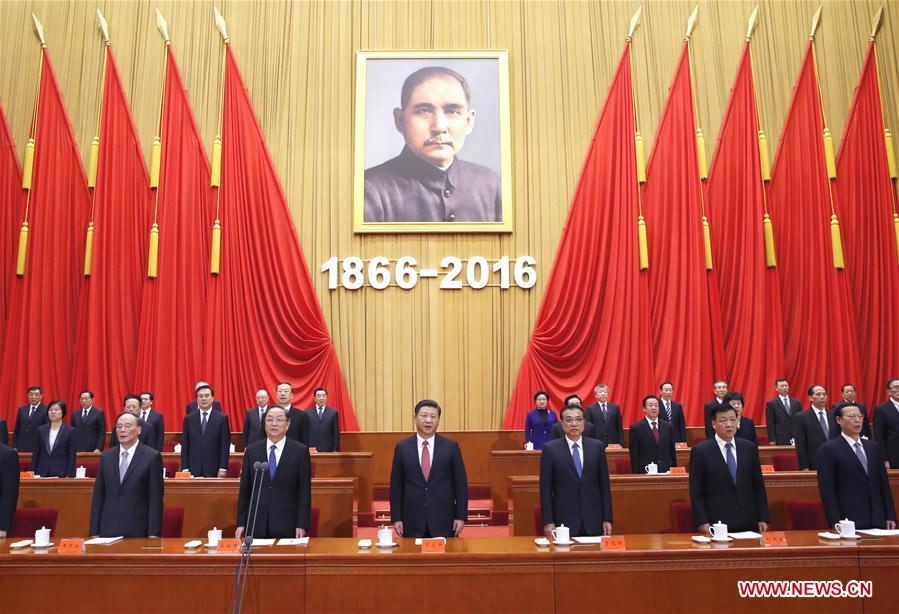

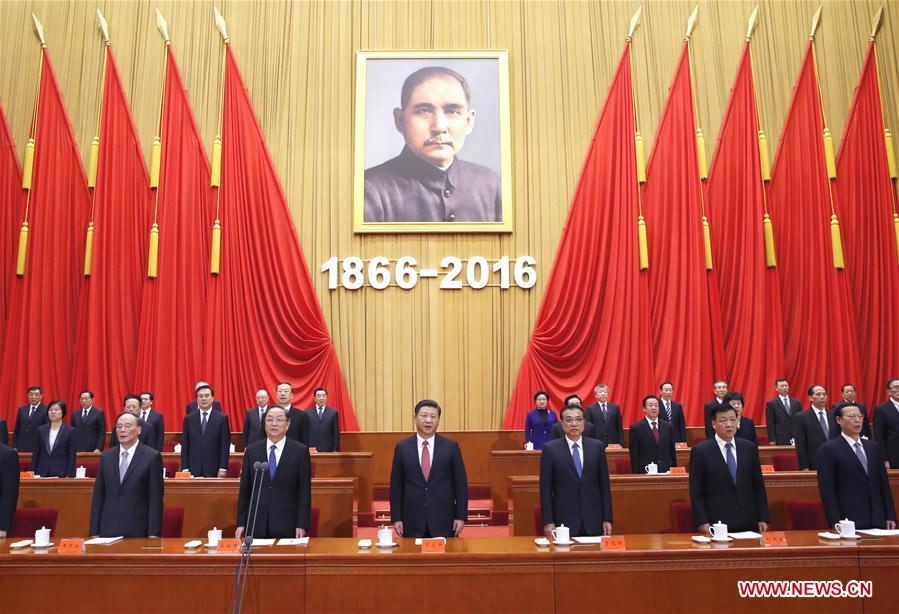

Senior Chinese leaders attend a gathering to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Sun Yat-sen's birth in Beijing, November 11, 2016. Sun is a revered revolutionary leader who played a pivotal role in overthrowing imperial rule in China. /Xinhua Photo

Senior Chinese leaders attend a gathering to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Sun Yat-sen's birth in Beijing, November 11, 2016. Sun is a revered revolutionary leader who played a pivotal role in overthrowing imperial rule in China. /Xinhua Photo

Yuan Weishi, a renowned professor from Guangzhou-based Sun Yat-sen University, held a similar view. He said reform required the Qing rulers to put limits on their own power but they refused to do so. As a result, more and more intellectuals and even some within the ruling class lost patience, choosing the path of revolution over hypocritical reforms, he suggested.

"The government must act decisively on reform, especially political reform," Yuan stressed in an article a few years ago. "This is the most important lesson left by the Qing Empire."

Reforms in 'deep-water zone'

"The best way to commemorate the Xinhai Revolution is to press ahead with reforms," Yang Yuze, a current affairs commentator, wrote on Legal Daily in 2011 in honor of the 100th anniversary of the revolution.

Today, as reforms in China have entered a "deep-water zone" – many of the easier reforms have been accomplished, leaving difficult tasks – the lesson of the revolution over a century ago still counts.

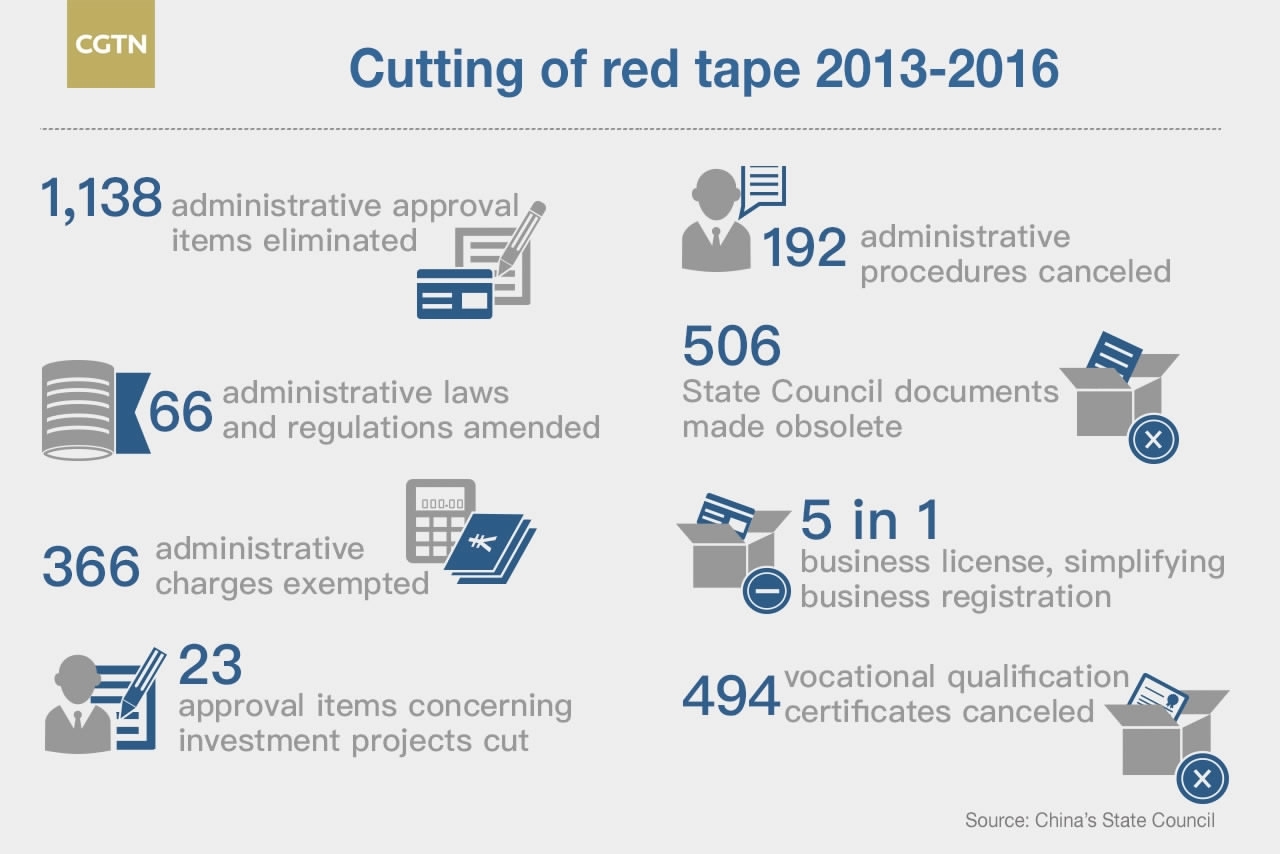

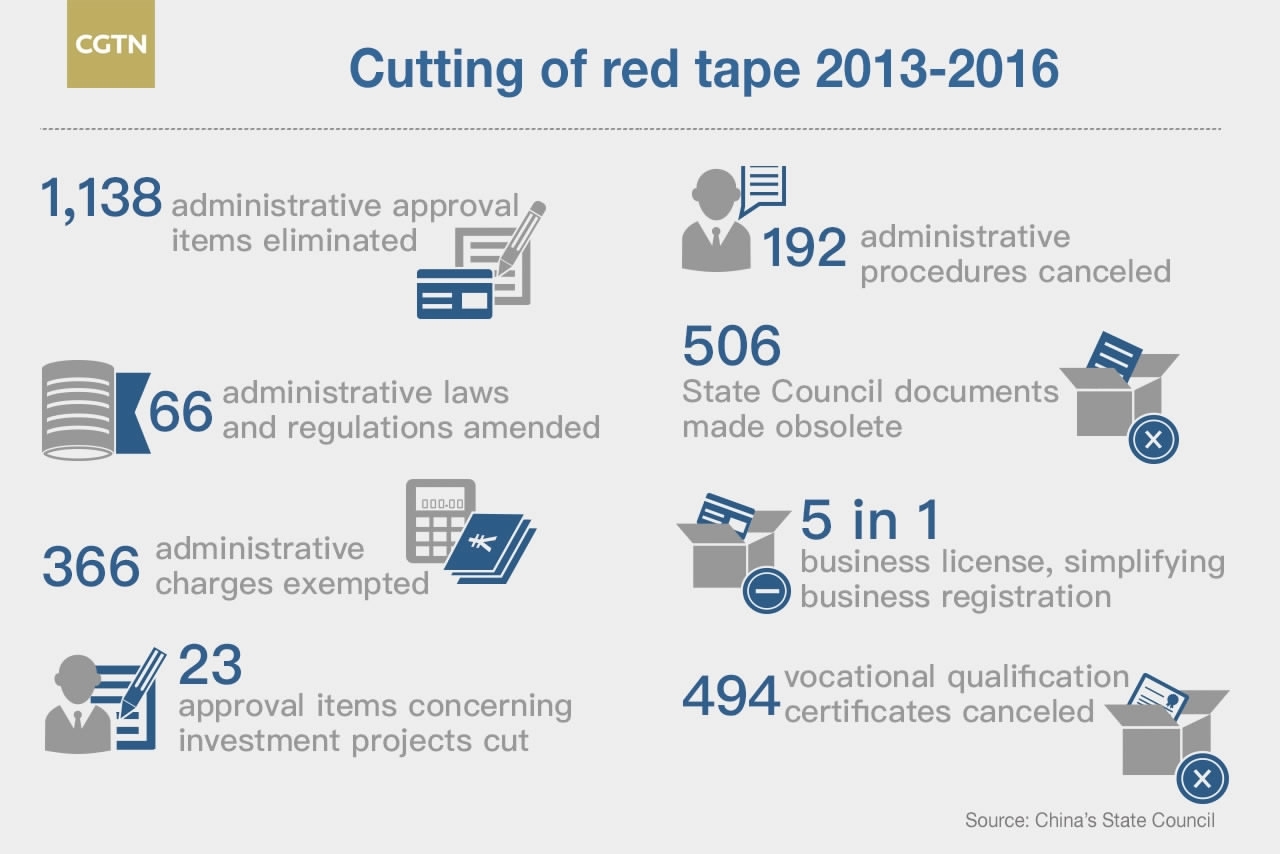

China aims to transform government functions, delegate more powers, improve regulation and service and give the market more freedom to take its course. /CGTN Graphic

China aims to transform government functions, delegate more powers, improve regulation and service and give the market more freedom to take its course. /CGTN Graphic

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 2012 and the Third Plenary Session of 18th CPC Central Committee in 2013, China has implemented comprehensive reform in various areas including economy, finance, government functions, urbanization, innovation, ecological improvement and rule of law, greatly enhancing the people's sense of gain.

The upcoming

19th CPC National Congress is expected to give more answers on how the ruling party will deepen the ongoing reforms and overcome the resistance of vested interests, paving the way for a more prosperous China.