Business

12:20, 28-Oct-2017

Can China become rich before growing too old?

By CGTN’s Yang Jing

“It’s much better to stay in this nursing home than being at my own home alone,” 85-year-old Beijing citizen Liu Xiuqin told CGTN on Wednesday, noting it is difficult for families to offer all-day care at home for the elderly.

The growing number of old people is putting pressure on China, especially when the country needs a large workforce to sustain its impressive economic growth.

China’s aging population

China officially became an "aging society" in 1999, defined by the UN as a country where 10 percent of its population are aged 60 and above.

At of the end of 2016, 16.7 percent of China's popualtion was aged 60 or above and 10.8 percent were older than 65, according to China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs data released in August.

This percentage is expected to grow with the peak predicted to come in 2055, when 400 million people, or 27.2 percent, of China’s population should be aged 65 or older, according to estimates by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Meanwhile, China’s average life expectancy has increased dramatically from 43.4 years in the early 1950s to today’s 75.4.

Although the aging population is a global issue, especially among developed economies, China is facing a difficult combination of factors - an aging population while at the same time it still has a relatively low per capita income.

When China became an "aging society" in 1999, its GDP per capita was only around 1,000 US dollars while other developed economies crossed the threshold into the category with GDP per capita incomes as high as 5,000 to 10,000 US dollars.

Compared to its neighbor Japan, China’s current population structure is like Japan’s in the 1980s, but China’s per capita GDP is more similar to Japan’s in the early 1970's.

Pension pillars under pressure

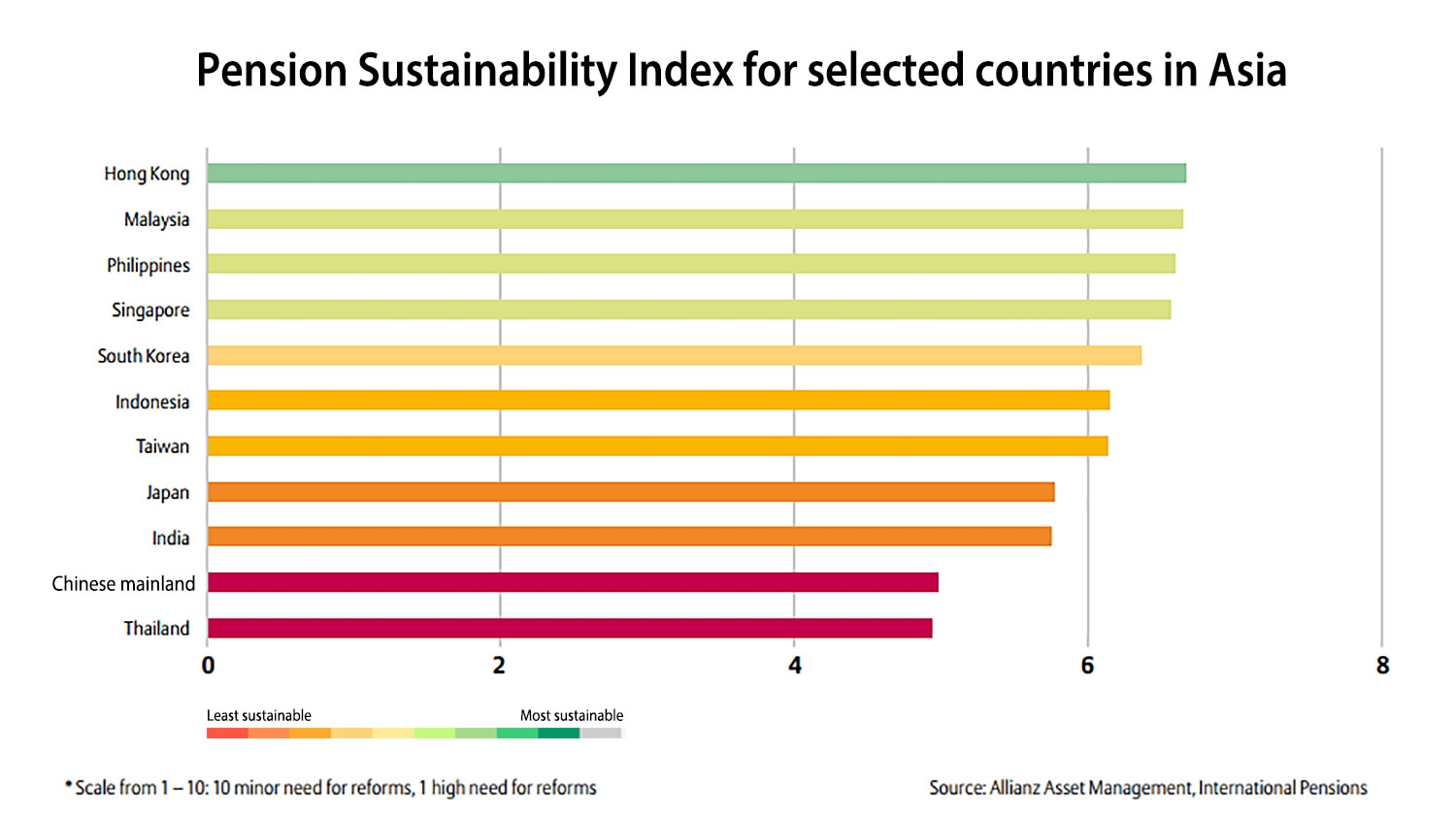

China’s fast growing aging population is expected to weigh on public finances, especially its pension system. The country's pension system ranks relatively low by international measurements when compared to other Asian countries, most notably because of how it is "balanced" between different types of pension schemes.

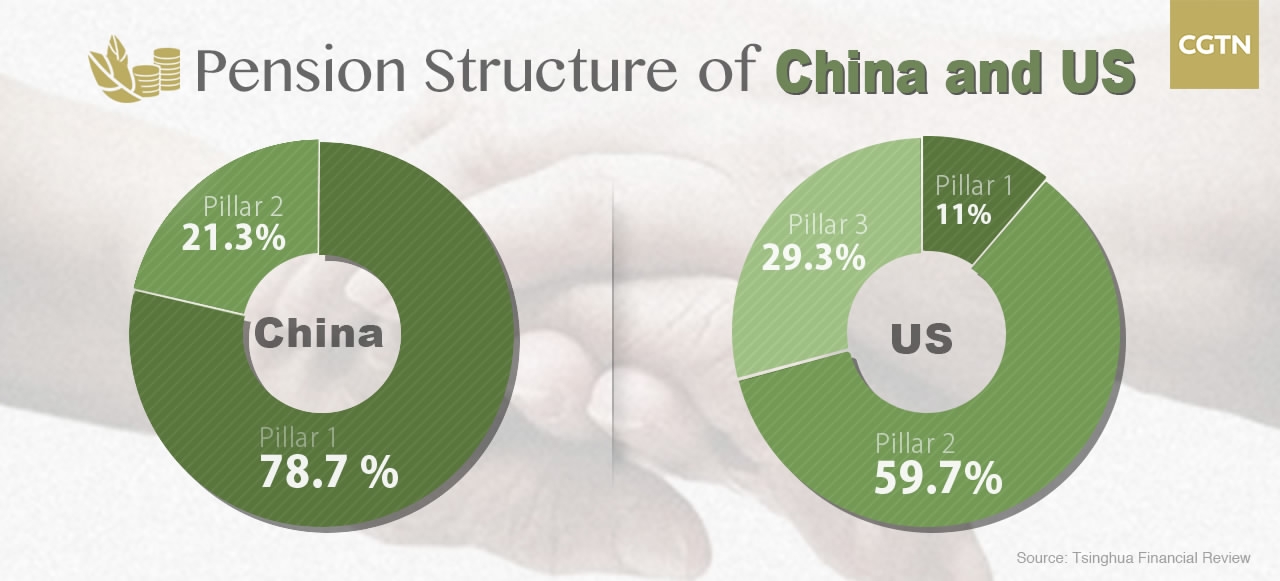

According to pension formats outlined by the World Bank, there are three pillars of a pension system designed to share the pension pressure by government, enterprises and individuals.

The first pillar is a standardized, state-run pension system, which offers basic coverage and is primarily focused on reducing poverty.

The second one is a funded system that recipients and employers pay into, including pension funds and defined-contribution accounts/plans.

The third one is voluntary private funded accounts, including individual savings plans, insurance, etc

Compared with developed economies, China’s pension structure is unbalanced with an over-reliance on the first pillar.

For instance, in the US, the first pillar accounts for 11 percent of total pensions and the second pillar shoulders the majority of 59.7 percent. In China, the first pillar takes 78.7 percent, and the third pillar has not even been established yet, according to a pension study published by Tsinghua Financial Review magazine in March with data compiled from 1997 to 2014

Moreover, with the first pillar is a “pay as you go” operation, which means using the money currently being contributed by young people to pay current pensioners, there is a growing risk that when the baby boomers, who were born before China’s one-child policy, get old, the pool of young people who can pay the pensions of their older country folk will dry up.

The pressure has already started to manifest itself. Official data showed that in China there are 3.04 workers to support each retiree, but the ratio will drop to 2.94 by 2020 and 1.3 by 2050.

To ease the pressure, China has considered to gradually postpone the retirement age from the current age 60 for males and 50 for females to 65 and 60 respectively. And the plan may be implemented gradually from 2022.

Booming need for nursing homes

In China’s traditional culture, people tend to stay in their own home and be cared for by family members. However, with the busy life and large aging population, more and more elderly prefer nursing homes.

In the Zhaoru elderly nursing home, which is located in Jingshan, the center of Beijing, there are 24 elderly people with an average age of 85 years old.

The place, a traditional Beijing-style yard is provided by local government while a private enterprise Beijing Zhaoru Health Tech Co Ltd invested in running the nursing home, Chen Zhanli, director of the nursing home told CGTN on Wednesday, noting the cooperation between government and private sector has been mainstream in elderly nursing industry.

With a monthly cost around 4,000 yuan (601 US dollars), Zhaoru targets the working class elderly. While many insurance and financial service conglomerates often aim at the high-end elderly nursing business. China’s Taikang Group launched a continuing care retirement community (CCRC), a nursing model from the US, with an insurance fee threshold as high as 2 million yuan.

The supply of nursing homes still falls short of surging demand. Although the number of elderly nursing institutes grew 20 percent year-on-year in China in 2016, on average there are only 31.6 nursing beds for each thousand elderly people in the population, according to official data.

To ease the imbalance, China has encouraged private and foreign capital to invest in the elderly nursing industry with “fully open access” since 2012, combined with preferential tax policies, in a bid to create an elderly nursing system with support from communities and nursing institutes.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3