Appeal proceedings began on Wednesday in France for two former Rwandan mayors convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life in prison in 2016 for their role in their country’s genocide.

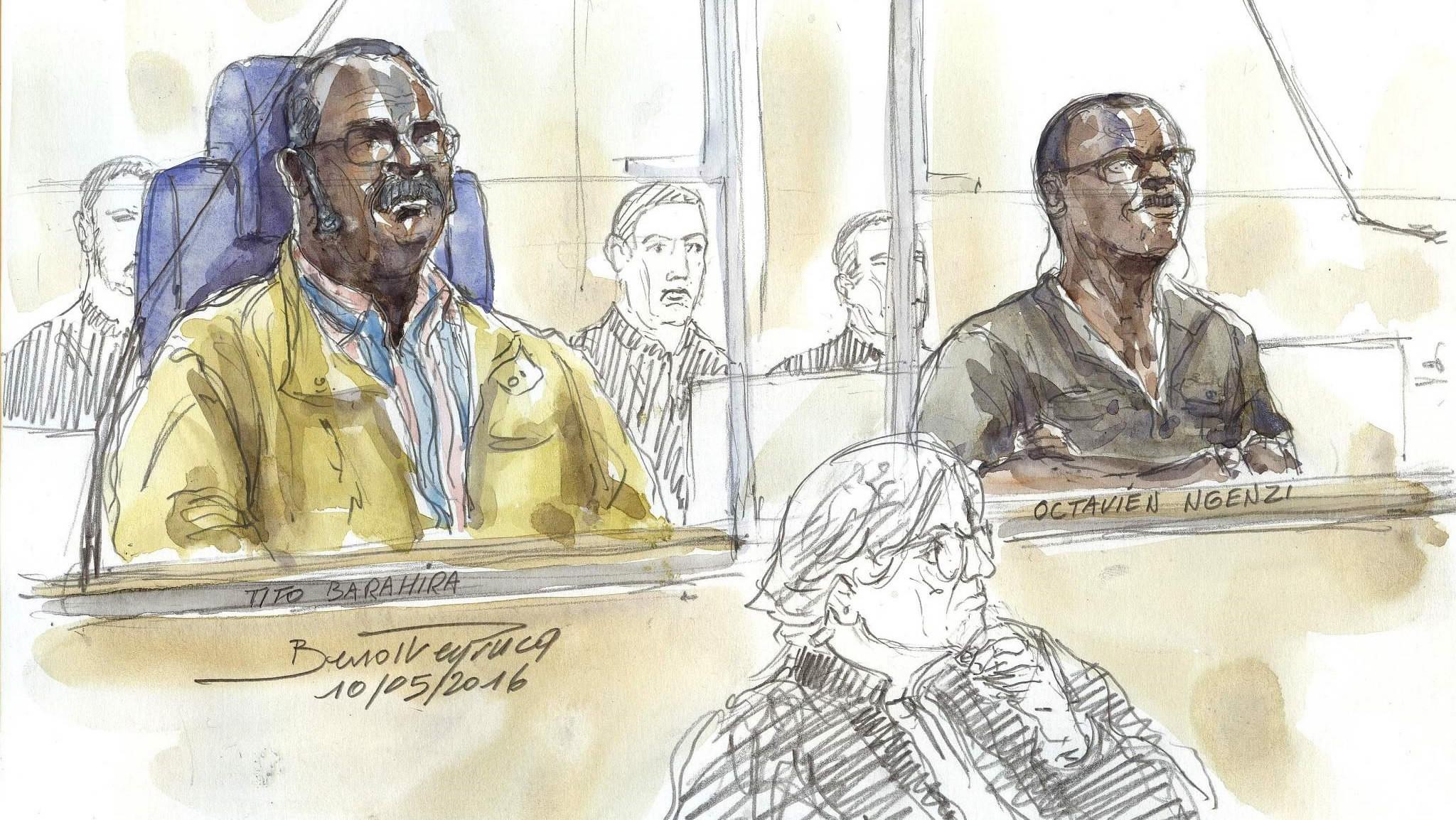

The two men, Octavien Ngenzi, 60, and Tito Barahira, 66, were successively mayors of Kabarondo, a village in eastern Rwanda, when the African country descended into chaos in 1994.

Brought to trial in France, where they now live, they were found guilty in 2016 of genocide and crimes against humanity for the "massive and systematic summary executions" of minority Tutsis by ethnic Hutus in Kabarondo.

The two men have however maintained their innocence.

A government soldier guards a Hutu refugee camp in a village in southern Rwanda, April 26, 1995. /VCG Photo

A government soldier guards a Hutu refugee camp in a village in southern Rwanda, April 26, 1995. /VCG Photo

Rwanda, 1994

An estimated 800,000 people were killed in a matter of months in 1994, as ethnic tensions reached a climax and gangs and militias – mainly from the Hutu ethnic majority, and most of them wielding machetes – went on a rampage, massacring people, many of them from the Tutsi minority.

In the case of Kabarondo, over 2,000 people were killed in just one day in April 1994, as they tried to find sanctuary in a church.

International tribunals

Within months of the killings, which shocked the world, an International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda – modelled on a similar court investigating war crimes in the former Yugoslavia – was set up in Tanzania to prosecute those responsible for crimes against humanity and genocide.

The ICTR ran for 21 years and led to 61 convictions before it shut its doors in 2015.

Hundreds of crosses mark the mass grave in which some 600 civilians were massacred in April l994 during the genocide by Hutu militias of up to one million Tutsis. /VCG Photo

Hundreds of crosses mark the mass grave in which some 600 civilians were massacred in April l994 during the genocide by Hutu militias of up to one million Tutsis. /VCG Photo

Other countries, such as France, have since picked up the mantle: the fact that some of the victims were French citizens gave French courts jurisdiction to issue arrest warrants and start trial proceedings.

There are now about two dozen cases relating to the Rwandan genocide underway in French courts.

Appeal

Ngenzi and Barahira’s life sentence in 2016 was the toughest handed down by a French court. It was also just the second Rwanda-related conviction issued in France after that of Pascal Simbikangwa, a former Rwandan intelligence agent, who was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2014.

Prosecutors accused Ngenzi during the first trial of being an "opportunist" who "went over to the dark side" when the killings began. Barahira was accused of denying that the genocide even happened.

In a statement on Wednesday, the Human Rights League (LDH), a French NGO involved in the trial, cited the 2016 court ruling, saying Ngenzi and Barahira "stood at the center of local political and administrative life" in Kaborondo in April 1994.

Young Ugandan children stand on the banks of the Kagera River in Rakai District on April 21, 2018 as people mark the 24th anniversary of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi people in neighbouring Rwanda. /VCG Photo

Young Ugandan children stand on the banks of the Kagera River in Rakai District on April 21, 2018 as people mark the 24th anniversary of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi people in neighbouring Rwanda. /VCG Photo

As such, they participated in meetings to coordinate attacks against Tutsis, led attacks against refugees and "oversaw large-scale killings" in the region, LDH said in the statement, published in French.

"The victims have waited more than 25 years for justice to be served," it concluded.

Alain Gauthier, a campaigner for victims' families, was meanwhile optimistic: "We expect the verdict to be upheld," he told AFP news agency.

'Political' trial?

Ngenzi’s son Maxime Gidishya however slammed the trial for being "political." "My father didn’t do anything. Whatever they’re looking for, they won’t find anything because my father didn’t do anything," he told reporters.

"We expect France’s justice system to be independent, to stay independent, and to really look at who my father was, what he did during the war and the genocide."

A boy looks at a memorial plaque at Kasensero genocide memorial site on April 21, 2018 during the 24th commemoration of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. /VCG Photo

A boy looks at a memorial plaque at Kasensero genocide memorial site on April 21, 2018 during the 24th commemoration of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. /VCG Photo

Ngenzi and Barahira have spent respectively eight and five years in prison so far.

The appeal proceedings are due to last two months, until July 6, with witnesses expected to testify in person or via video-conference from Rwanda.

Ngenzi’s lawyers have also said they want to call current Rwandan Defense Minister James Kabarebe as a witness before the court.

(With input from wire agencies)

(Top picture: A courtroom sketch made on May 10, 2016 shows Tito Barahira (back, L) and Octavien Ngenzi (back, R) at their trial together in Paris, France. /VCG Photo)