Opinions

10:39, 24-Aug-2018

The Heat: Racism debate boils in Brazil

Updated

09:52, 27-Aug-2018

CGTN's The Heat

01:30

The problem of racial discrimination in Brazil has long been swept under the carpet.

A recent telenovela, or soap opera, presented only 4 out of 27 characters as black or mixed race in a country where 80 percent of the population is black. This reignited the discussion about race, fueling a widespread debate that finally drew government attention, which then urged the TV station to reconsider its casting.

Luciana Tostes, a public prosecutor, said that the problem has gone on for too long.

“We have already passed the point of discussing this problem,” she said in a recent interview. “Now is the time when no media can run away anymore. We need to do something to solve it.”

An African thinker and professor once gave a widely quoted definition of the issue: racism in Brazil is a perfect crime. So far, there are no laws in the country that will put racists into jails.

It’s hard to understand the present situation without looking at the history of Brazil. The Latin American nation had slavery until 1888, making it the last country to abolish human trafficking in the Americas. By then, Brazil had the largest population of African descent or heritage outside the continent, and was even called “the Africa in the West.”

But the government made little effort to integrate those of African descent with indigenous populations. This divide grew as the country industrialized and urbanized in the following 200 years.

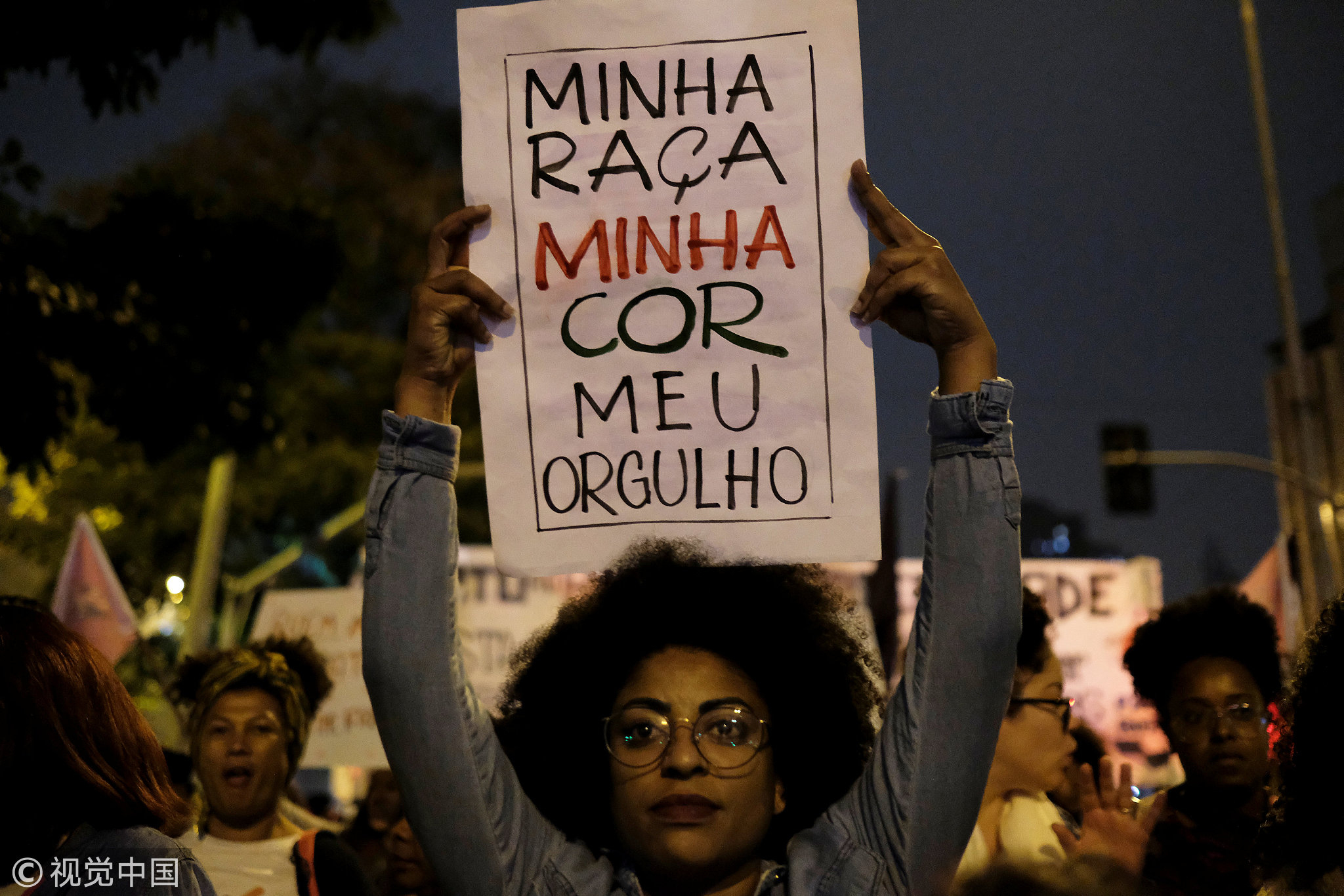

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "My Race, My Colour, My Pride " during a protest by black women against racism and machismo in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 25, 2018./ VCG Photo

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "My Race, My Colour, My Pride " during a protest by black women against racism and machismo in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 25, 2018./ VCG Photo

Racism was done away with only in the last one or two decades, according to Marcelo Paixao, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin researching race relations in Brazil. “What we have is ‘racial democracy’.”

The term “racial democracy” was initiated by the Brazilian government to indicate that race relations in the country had developed to where different races can live together without much conflict. However, Paixao said the concept has exacerbated the problem.

“The government supposed that we can achieve economic developments by a namely peaceful interaction between races,” he said. “But it turned out that our modernization is largely built on inequality and injustice.”

Marcelo Lins, a journalist for GloboNews, the country’s largest 24-hour news channel, summarized Brazil's racism with one word: “hypocrisy.”

“Our government turned a blind eye to the problem until recently,” he said. “You can barely see congressmen or professors in institutional or academic organizations. People with an African heritage are largely underrepresented.”

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "Black Lives Matter" while taking part in a protest by black women against racism and machismo in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 25, 2018./ VCG Photo

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "Black Lives Matter" while taking part in a protest by black women against racism and machismo in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 25, 2018./ VCG Photo

People who identify themselves as black or mixed race often face explicit and implicit discrimination in their everyday lives. For instance, a hiring note may use “good-looking” as a substitute for “non-black,” according to Marcelo.

Paulo Sotero, the director of the Brazil Institute at the Wilson Center, explained how “racial democracy” education can actually be detrimental.

“You grow up being educated that people from different races will not discriminate against one another, and you start to believe that baloney,” he said. “However, racism in Brazil is pervasive; it’s in the culture and language.”

Paulo recalls a joke that sardonically describes the country’s race relations: “Thank God we don’t have racism in Brazil, because black people know their place.”

However, there is still good news. As the debate on racism starts to boil, more people are joining the movement calling for equal economic and social status for black and mixed races.

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "Black Lives Matter" while taking part in a protest by black women against racism and machismo in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 25, 2018./ VCG Photo

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "Black Lives Matter" while taking part in a protest by black women against racism and machismo in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 25, 2018./ VCG Photo

Brazilian philosopher Djamila Ribeiro urged society to think about the problem together, instead of having isolated government officials carrying out unpopular projects.

“A national participation of the national project is rather important,” she said. “When people are discussing transportation, health and education issues, you have to take race into consideration.”

Meanwhile, Lins sees hope in the younger generation toward achieving racial integration, saying that he observes youth becoming more conscious than the older generation about the duties they bear to improve the situation.

Paixao reiterated his pride in his country’s different races. “The majority of our nation is black, and we are proud of that. It may surprise you that one of the most important authors of Brazil, Machado de Assis, is exactly an African descendant.”

The Heat with Anand Naidoo is a 30-minute political talk show on CGTN. It airs weekdays at 7:00 a.m. BJT and 7:00 p.m. Eastern in the United States.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3