Opinions

13:21, 06-Jun-2018

Opinion: SCO adapts to Eurasia's strategic realities

Richard Heydarian

Editor's note: Richard Heydarian is a geopolitical scholar, columnist and author. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is fast becoming one of the leading powerhouses outside of the West. From its humble, more ad-hoc beginnings at the dawn of the 21st century, when China, Russia and post-Soviet states sought to negotiate a new security architecture in Eurasia, the SCO is now on the verge of admitting all major powers across the Asian landmass.

A night view of Qingdao, east China’s Shandong Province. /VCG Photo

A night view of Qingdao, east China’s Shandong Province. /VCG Photo

Last year, the body admitted India and Pakistan, two large-sized nuclear powers with a deeply fraught history of rivalry and wars, as full members of the Eurasian organization. This is even more crucial when one considers the fact that both South Asian powers have also had a history of close strategic relationship with the United States.

While Pakistan has served as a linchpin in America’s Global War on Terror, India has rapidly become the West’s primary maritime strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific theatre. The two South Asian powers have also added geopolitical heft to the SCO. Together with Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, the SCO now represents a fifth of the global economy and up to 40 percent of world’s population.

Beginning in 2005, India and Pakistan became observer nations in the organization. But as the SCO’s institutionalization matured, and China expanded its global influence and deepened its commitment to shaping the Eurasian security architecture, then the organization became confident enough not only to admit two new large-size rival nations but perhaps even help ease their bilateral tensions and strategic differences.

Thus, the SCO is no longer seen as a threat to the West, but instead a post-ideological, functional and increasingly influential grouping in the Eurasian theatre.

During the upcoming SCO summit in Qingdao, there is a possibility that the long-running proposal for Iran’s full membership will be resolved with finality. As a major powerhouse in the Middle East and host to one of the world’s largest reserves of oil and gas, Iran naturally brings its strengths to the table.

Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani is expected to attend the Summit (June 9-10), where he will meet Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin to discuss ways to counter America’s unilateral withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPA) deal.

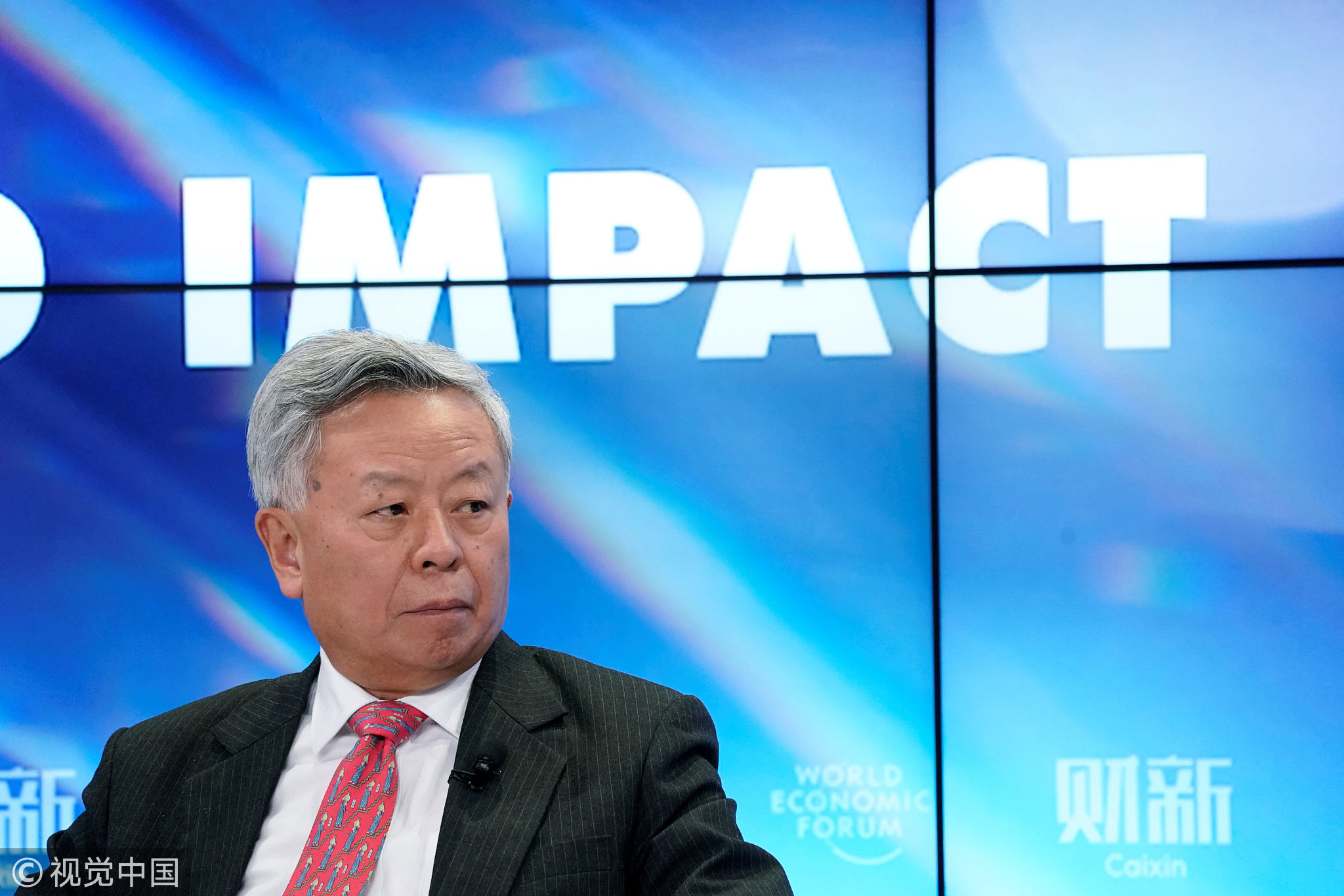

Jin Liqun, president of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, attends the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland on Jan 24, 2018. /VCG Photo

Jin Liqun, president of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, attends the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland on Jan 24, 2018. /VCG Photo

Both China and Russia, along with key European powers of Britain, France and Germany, support the Iranian nuclear deal and have vigorously opposed the Donald Trump administration’s plan to the scuttle the historic agreement through re-imposition of sanctions on Tehran.

This is why the meeting among the three powers is essential, precisely because it’s also about negotiating the parameters of a post-American order in the Eurasian region, where America doesn’t dictate strategic realities on other nations.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has expressed his support for the expansion of the SCO in light of its achievements. "SCO members have fought the three evil forces of terrorism, separatism and extremism and made important contributions to regional peacekeeping, development and prosperity," said the Chinese leader during the 13th meeting of Security Council secretaries of the SCO in Beijing.

With the inclusion of Iran, India and Pakistan in the SCO, China will play a more active role. Yet, the SCO also has specific functional purposes.

Its creation in 2001 was mainly an ad-hoc response to the necessity of addressing the new security and strategic challenges emanating from the collapse of the Soviet Union, the emergence of religious fundamentalism, and the development in China and Russia. Thus, the SCO’s creation served three inter-related purposes.

First, it symbolized an unprecedented period of strategic confidence and stability in Sino-Russian relations, as the two powers negotiated their interests in Central Asia and jointly supported the viability and development of post-Soviet nations in the area. In the preceding years, China skillfully and generously resolved much of its land-based border disputes with its Eurasian neighbors.

Secondly, the SCO provided institutionalized mechanisms for enhancing counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism cooperation among member states amid the rise of religious fundamentalism and infiltration of extremist groups in the post-Soviet space. Thus, Russia, China and Central Asian nations enhanced intelligence sharing, joint drills and military cooperation among each other.

Lastly, the SCO served as an encouraging model for other international organizations and platforms, including the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the New Development Bank (NDB) and, above all, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

What all these institutional arrangements underline is the growing importance of China as a norm-builder and its increasing convening power as well as the emergence of alternative mechanisms for dialogue and strategic cooperation outside the West. Together, they will allow Beijing to cooperate with the countries in the Eurasian region in a win-win, dialogue-based manner, in consultation with all the major stakeholders, from Russia to India, Pakistan and Iran.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3