Geopolitical voting, country boycotts and money issues… what started out as a project to unite post-war Europe has gone beyond music.

With boos ringing around the arena over votes thought to be inspired by geography and politics and countries dropping out of the competition due to issues beyond music, what started as a project to bring together post-war Europe has become something more than just a song contest.

Eurovision is a big deal. At 64 years old, it is the world's longest-running annual televised music competition, up to 44 countries can compete and last year the event attracted 186 million global viewers. This year's final, on May 18 in Tel Aviv, Israel, is expected to top that figure.

Read our guide to the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest

here.

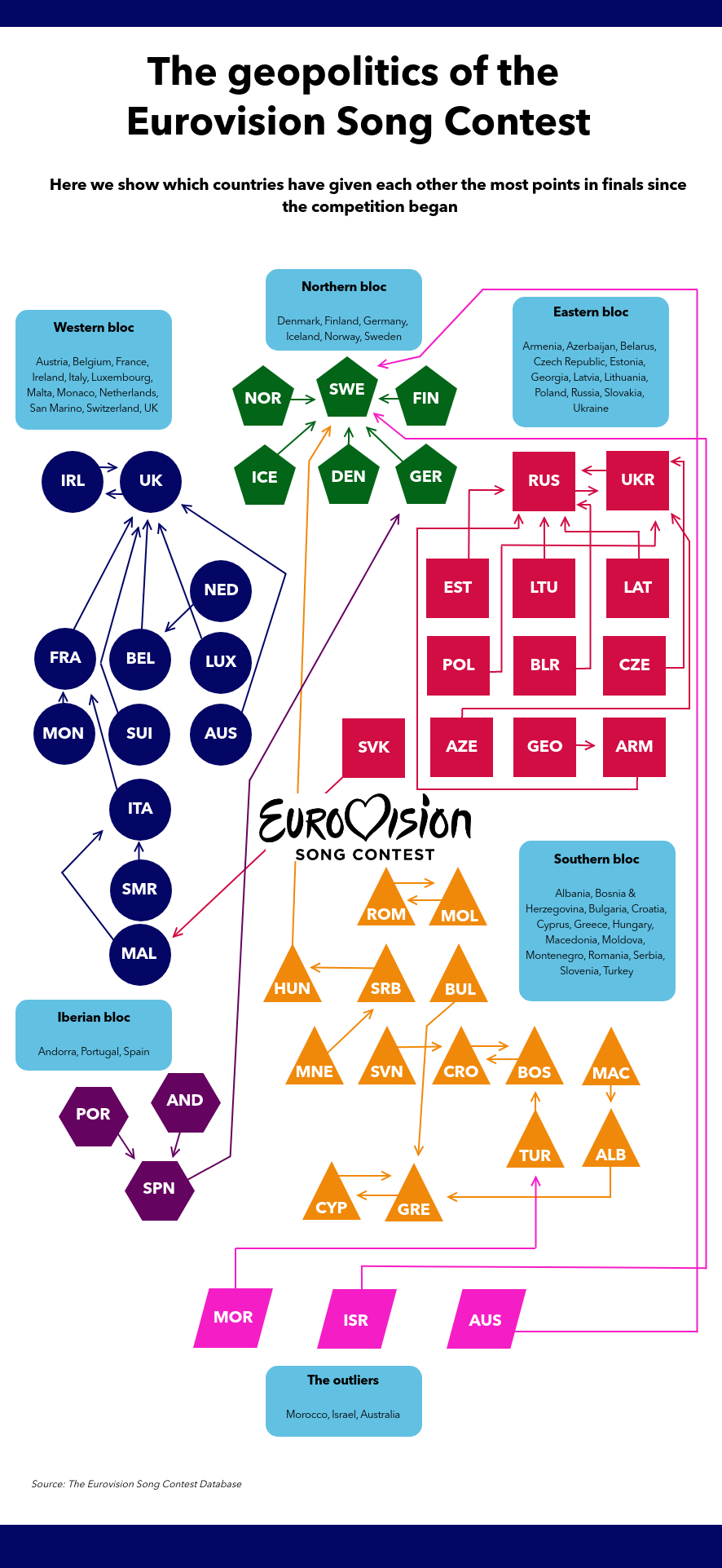

While voting in the contest has always had an element of presumed bias – the UK and Ireland could usually rely on a healthy number of votes from each other, as could Greece and Cyprus – the trend of putting geography over musical value has grown since the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

Austrian pop singer Conchita Wurst, the winner of the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest, seen during a dress rehearsal for the 1st Semi Final of the 60th annual Eurovision Song Contest, May 18, 2015. /VCG Photo

Austrian pop singer Conchita Wurst, the winner of the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest, seen during a dress rehearsal for the 1st Semi Final of the 60th annual Eurovision Song Contest, May 18, 2015. /VCG Photo

The official Eurovision rules state: “When voting, jury members shall use all their professional skill and experience without favoring any contestant on the account of their nationality, gender or likeliness.”

While the competition has proved itself inclusive in recent years in terms of transgender and gay contestants competing and winning – notably

Conchita Wurst for Austria in 2014 – the same cannot be said of bias towards nationality.

One look at the voting trends over the competition's history shows geographical allegiances hold strong.

Anger also surrounds the creation of the so-called "Big Five" in 2000, which refers to the UK, Spain, France, Italy and Germany – the countries that pay the most to the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), which presides over the event, and therefore guarantee a place in the final of the competition each year.

Turkey, which last participated in the contest in 2012, has previously cited the Big Five rule as one of the reasons for withdrawing from the competition, with national broadcaster TRT arguing the rule is unfair because all other nations have to go through the semi-finals.

On the official Eurovision

site, one fan called "Europe" wrote: “Outrageous!!! All countries should have the same chance!!! Even in Europe there is NO equality. POOOOR...”

While another called Sofie wrote: “It is not fair that the big five get to go straight to the final just because they donate more money. They should still have to perform in the semi-finals.”

Spain's Manel Navarro performs the song "Do It For Your Lover" during the Eurovision Song Contest 2017 Grand Final at the International Exhi-bition Centre in Kiev, Ukraine, May 13, 2017. /VCG Photo

Spain's Manel Navarro performs the song "Do It For Your Lover" during the Eurovision Song Contest 2017 Grand Final at the International Exhi-bition Centre in Kiev, Ukraine, May 13, 2017. /VCG Photo

However, Frank Dieter Freiling, chairman of the Eurovision Song Contest reference group, the event's steering committee, said the Big Five is here to stay: “The major part of televotes is coming from the big countries. The rule was implemented to make sure that the majority of spectators and thus the majority of televoters who live in the big countries can enjoy the show and take part in the voting process, and I think that this has proven to be a good solution.”

Russia and Ukraine

This year, 41 countries will compete in the contest. There were supposed to be 42 nations involved, but Ukraine pulled out in February. This wasn't due to financial constraints – as was the case for Bulgaria, which said it couldn't afford to compete this year – but because of a row between its state broadcaster and the singer who won the country's public vote to decide who would perform.

Maruv was dropped by UA:PBC after she refused to sign a contract, which included restrictions on performing in Russia. On her Facebook account, the singer wrote: “I am a musician, not a puppet for the political arena.”

The state broadcaster had the same problem with the acts that finished in second and third place and UA:PBC released a statement which read: “The national selection this year has drawn attention to a systemic problem with the music industry in Ukraine – the connection of artists with an aggressor state with whom we are in the fifth year of military conflict.”

Sergey Lazarev representing Russia performs with the song "You Are The Only One" during the Eurovision Song Contest final at the Ericsson Globe Arena in Stockholm, Sweden, May 14, 2016. /VCG Photo

Sergey Lazarev representing Russia performs with the song "You Are The Only One" during the Eurovision Song Contest final at the Ericsson Globe Arena in Stockholm, Sweden, May 14, 2016. /VCG Photo

This follows Russia pulling out of the 2017 competition a month before it was due to start – again due to its relationship with Ukraine. That time, Ukraine barred Russian contestant Julia Samoylova because she had toured in Crimea in 2015 after Russia-Crimea conflict.

The EBU offered possible solutions including Samoylova performing via satellite or for the country to instead field a contestant who could legally travel to Ukraine. But Russian broadcaster Channel One turned down both options.

Freiling said at the time Ukraine's decision “thoroughly undermines the integrity and non-political nature of the Eurovision Song Contest and its mission to bring all nations together in friendly competition.”

Interestingly, Russia and Ukraine have given each other the most votes over the course of the event's history (see infographic).

Money, money, money

And it's not just the voting that causes problems. Israel has been at loggerheads with the EBU over the security costs for this year's event and held up 1.5 million shekels (420,000 U.S. dollars) of payments.

Israel's singer Netta Barzilai aka Netta performs with the trophy after winning the final of the 63rd edition of the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 at the Altice Arena in Lisbon, on May 12, 2018. /VCG Photo

Israel's singer Netta Barzilai aka Netta performs with the trophy after winning the final of the 63rd edition of the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 at the Altice Arena in Lisbon, on May 12, 2018. /VCG Photo

In April, Jon Ola Sand, Eurovision's executive supervisor, wrote to Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel's prime minister, warning his country's foot-dragging could put the contest in jeopardy.

Following the letter, the Prime Minister's Office announced it would cover the extra cost, taking its total security budget to 7.5 million shekels.

Also, this year U.S. pop star Madonna will perform during the interval – which we can assume will not be cheap.

Indeed, winning the competition is sometimes seen as a poisoned chalice. Ireland is the most successful nation in Eurovision history, winning the contest seven times. But after three straight wins from 1992-94, representatives from Ireland's state broadcaster, RTE, were said to have expressed concern about having to stage the contest for a third consecutive year and put forward a song they thought wouldn't win. They were right – Norway took the title that year. Unfortunately for the broadcaster, the country went on to win again in 1996, leaving RTE picking up the tab for staging its fourth contest in five years.

So, while the contestants will be doing their best to hit the right notes at the final on May 18, the battles behind the scenes will not be as harmonious.

(Top image: During the rehearsal of the first semi-final of the Eurovision International Song Contest 2015 in Vienna. /VCG File Photo)