Opinions

13:13, 23-May-2018

Opinion: Will the Korean Peninsula backslide into same old scenario?

By Wang Xiaonan

Editor’s note: Wang Xiaonan is a journalist for CGTN Opinion. East Asian Studies expert Zheng Yongnian was interviewed. The videos were produced by CGTN videographer Geng Zhibin.

“We’ll see what happens,” said Donald Trump on Tuesday local time, casting doubt on the scheduled Singapore summit with Kim Jong Un. “There’s a very substantial chance that it won't work out,” the US president said while meeting with his counterpart from the Republic of Korea (ROK), Moon Jae-in, who was in Washington to exchange “ideas” on how to keep the dialogue with Pyongyang alive.

Now it seems Seoul's role is fleetingly diminishing and the Korean Peninsula is very likely to backslide to the seven-decade-long stalemate.

Trump’s rhetoric further fueled the latest “fire and fury” surrounding the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) given a sequence of distressing events.

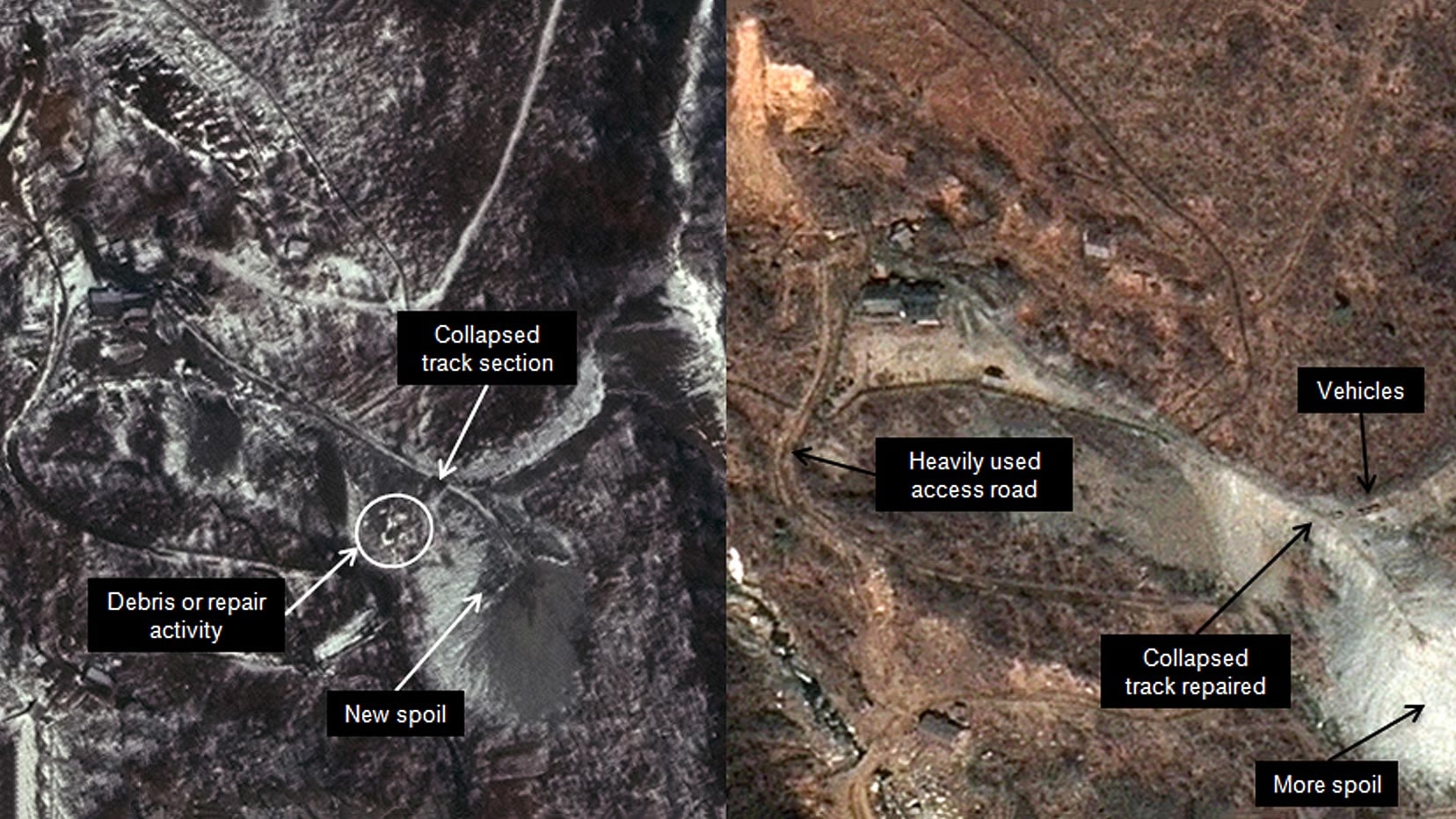

In mid-May, at the last minute, Pyongyang called off at the North-South talks slated for May 16 and announced it would reconsider the historic Kim-Trump summit on June 12. Days ago, it denied media from the ROK access to the Punggye-ri nuclear test site where all six nuclear tests were launched.

The DPRK cited the unabated US-ROK military drills and Washington’s unilateral demand to abandon nuclear weapons as the reason for putting the original plans on shaky ground.

Moreover, the country was still rankled by US National Security Adviser John Bolton’s "Libya model" remarks. Kim knows well what the model indicates given the eventual death of the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. Though the White House contradicted Bolton’s hawkish suggestion, Pyongyang’s repugnance to Washington and possibly its ally Seoul only grew.

Across the pond, Trump rendered a vague response. “We’ll see,” he said when asked about whether the summit with Kim will happen at all. He no longer vaunted “I alone can fix it” as he once did during the presidential campaign; nor did he back down from his “maximum pressure” policy on Pyongyang.

In a blink of an eye, the whirlwind of high-wire diplomacy was followed by a whirlwind of rapid-fire setbacks, once again plunging the fate of the Korean Peninsula in uncertainty.

The fundamental reason that the two sides are playing hardball against each other is that both lack even the base level of trust, said Zheng Yongnian, director of the East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore. “For over half a century, they did not have official contact,” he told CGTN.

01:13

As for the summit itself, though hailed as a historic breakthrough, the international community should not pin high hopes on it. Even if it happens in time, as US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo optimistically promised to work on, it can hardly yield any substantial results.

The DPRK and the US-ROK alliance have long been mired in mutual distrust. A bunch of US politicians and Western media outlets have spent the past months probing into whether Kim’s diplomatic overture is a smoke shell to gain relief from economic sanctions, as they once did when Kim’s father met with former ROK presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun.

Again, they have spent the past few days wondering whether Pyongyang’s altered position is a negotiation ploy or indeed a prelude to scrapping the summit.

It’s very much like what Trump did in dealing with Cuba, said Zheng, also director of the Academic Committee of the Center for China and Globalization. After the real estate tycoon took the Oval Office, he reversed his predecessor Barack Obama’s policy of engaging Cuba to normalize Washington-Havana ties. "We can see a rollback in relations between Cuba and the United States, in the statements of the US authorities, an aggressive and threatening tone prevails," said then Cuban president Raul Castro.

Ultimately, the DPRK is wary of the US’s promise of providing economic relief and government stability after it denuclearizes. Pyongyang only needs to look to history when Washington's support turned to regime change after the issue of nuclear weapons came into play. Libya had given up its nuclear arms program after a crippled economy pushed it to seek help from the US, only for Gaddafi to fall after a political uprising.

Similarly, the US had provided material assistance to Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1970s, but it invaded Iraq in 2003 under the pretext of the latter building up a nuclear facility and sponsoring terrorism.

More recently, the White House reneging on the Iran nuclear deal doesn’t inspire confidence either. Kim might be concerned that trading his nuclear weapons for economic growth will leave him with neither in the end.

00:35

In addition, regional stakeholders have yet to reach minimum consensus on the core of the conundrum – denuclearization. “Kim's denuclearization is different from what Trump talked about it, and even different from what we talked about it here in China,” Zheng noted.

The White House demanded “complete, verifiable, irreversible dismantling” of nuclear arsenals by the DPRK – the terminology of which was later changed to “permanent, verifiable, irreversible dismantling” by Pompeo. But Pyongyang insisted on a phased approach to denuclearization, accompanied by the alleviation of UN sanctions.

Beijing supports Kim’s policy toward a nuclear-free peninsula, but the precondition is that the existing government must be maintained. Hence, China will discourage external pressure because that would contribute to volatility.

In light of lack of base-level trust and minimum consensus among parties involved, the diplomatic rapprochement will likely turn into a fiasco.

Nonetheless, there’s encouraging news coming in when writing on the gloomy prospect. The DPRK made an overture to the ROK, allowing the latter’s reporters to join their Chinese, Russian, US and UK counterparts in witnessing the dismantling of the Punggye-ri nuclear test site.

Meanwhile, a ROK government spokesman announced in Washington that the pending inter-Korean high-level talks will probably resume after the US-ROK military exercises end on May 25.

So, we’ll see what will happen.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3