China

16:49, 27-Dec-2018

Chinese society: The good, bad and ugly of 2018 (II)

Updated

16:41, 30-Dec-2018

By Wang Xiaonan

The year 2018 is drawing to a close. Looking back, waves rippled across Chinese society. We saw good and bad things, we felt both grief and joy, we lamented social ills and also lauded progress.

We've selected six events that have defined the year. These heart-wrenching tragedies, controversial scandals as well as hard-earned advancements unleashed humanity's darkest instincts as well as demonstrated the triumph of the human spirit so that we find our future not that far from assured.

The article is the second in a two-part series on the controversial social issues of China in 2018. The first article can be found here.

04:01

'Dying to Survive' comes true

The prohibitive costs of life-saving drugs dominated public discussion this year. It began when Chinese Premier Li Keqiang announced in March that authorities will do away with tariffs for imported cancer drugs from May 1. A slew of other measures were also announced to cut costs, such as buying medicine in bulk for cheap and including new medications under the national health insurance scheme.

Then domestic media lit up when the film "Dying to Survive" debuted in July, which centers on a Shanghai businessman who smuggles cheaper generic drugs from India to save leukemia patients. The plot is based on the real story of Lu Yong, who was briefly jailed for doing so before a judge decided to release him.

Besides being one of the year's top box-office earners, the film brought the needs of cancer patients to the forefront of public consciousness once again, and highlighted how expensive critical drugs can be for those who have no choice but to buy them. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying cited the movie while announcing at a press briefing that the country has reached a deal with India to increase drug imports at reduced tariffs.

Reforms in the healthcare sector continue, as the Chinese government implements a policy to buy drugs in bulk, awarding contracts to drug producers for certain medications such as imatinib for leukemia and gefitinib for lung cancer. The initiative has already resulted in average drug cost reductions of over 50 percent for the 25 drugs on the procurement list.

Challenges abound on the road to reform, however, as all parties – including patients, drug producers, healthcare providers, and regulators – find a new equilibrium to adapt to.

00:55

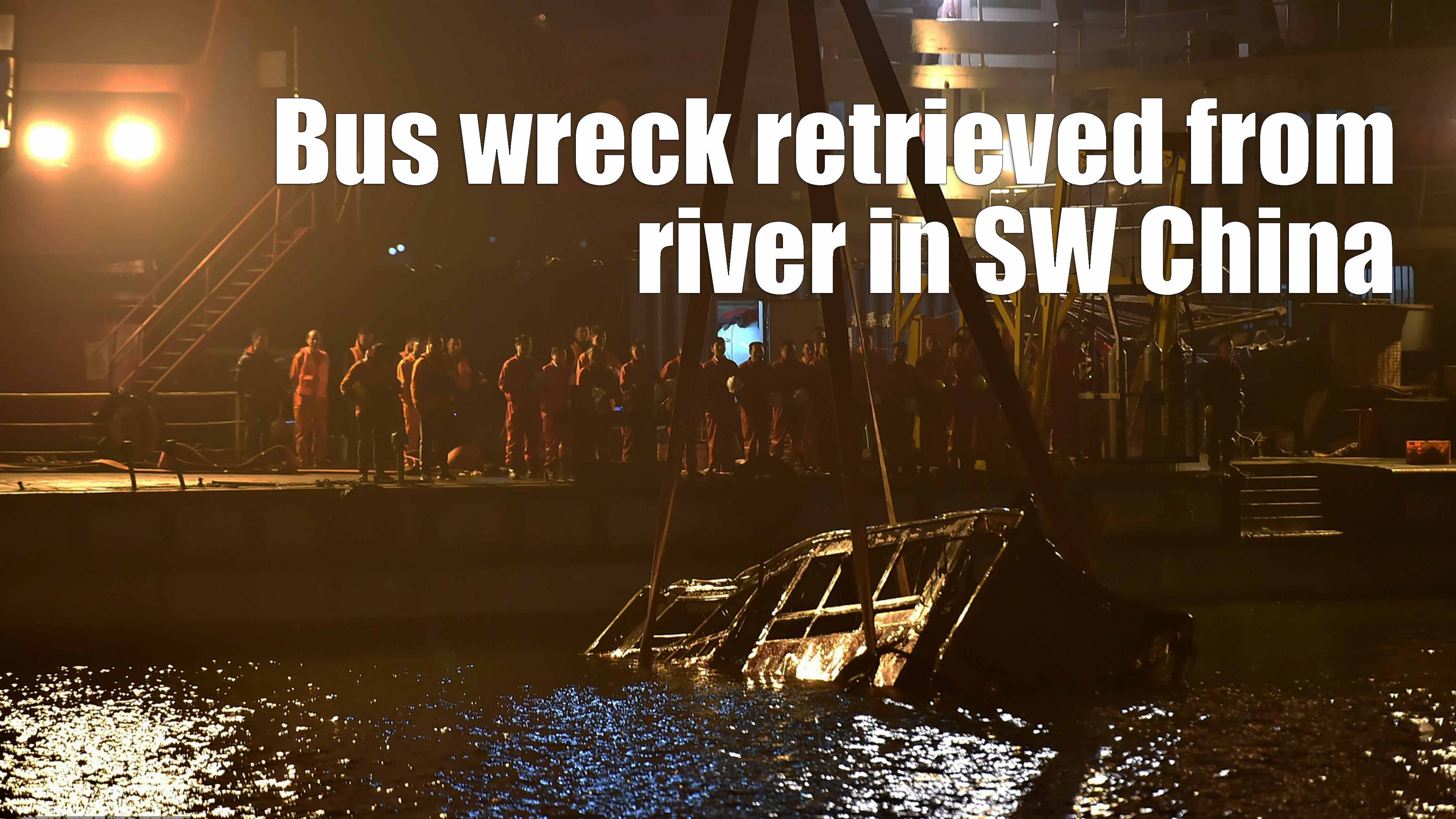

Anger, apathy in Chongqing bus crash

A bus plunged into the Yangtze River in southwest China's Chongqing on October 28, killing all 15 on board, including the driver. A video retrieved from the vehicle's black box showed how a brawl between a passenger and the driver led to the tragedy, leaving the public in shock.

It turned out that a 48-year-old woman started hitting the driver when he rejected her request to pull over immediately after she had missed her stop. After exchanging blows, the driver swerved to the left, lost control of the vehicle, collided with an incoming car in the opposite lane, and plowed through the bridge's rail guard before falling into the river.

In the wake of the fatal accident, Chongqing authorities held a meeting on public transportation safety. They vowed to provide better protection for public bus drivers, such as installing driver cabins, like on British buses, and having a conductor on all buses, which Beijing has already adopted. They also encouraged observers of such incidents to be "Good Samaritans," not indifferent onlookers.

It seems everyone on board the doomed bus played a part in the tragedy. The woman behaved rudely, the driver lost his rationality, and the remaining passengers were apathetic.

The World Health Organization estimated that 260,000 people are killed in road accidents in China every year. To bring down this figure needs the efforts of both drivers and passengers. They need to know that abiding by the rules and displaying public virtues are critical to their own safety.

One month later after the calamity, the municipality witnessed a similar incident when a man grabbed the steering wheel of a coach bus running on the Qijiang-Wansheng Highway after getting on the wrong vehicle. But this time, things went differently. Four passengers rushed to restrain him and handed him to law enforcement on the highway.

Read more: Chongqing bus footage shocks netizens, Nanjing introduces cash rewards for calm bus drivers

02:17

Baby gene editing causes fear

On Nature's list of the top 10 people who mattered in science in 2018, He Jiankui was the one and only controversial name. The renowned scientific journal dubbed him "the CRISPR rogue" for his "memorable" behavior that forced people to "confront difficult questions about who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going."

He, an associate professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, became a household name in late November when he announced he had created the world's first genetically edited babies by altering their DNA as embryos with CRISPR to protect them from HIV infection. His experimentation had neither ethical approval nor peer review.

The move has roiled the international scientific community, as he crossed the ethical red line and exposed the twins to potential risks. And whether the infants are resistant to all forms of the HIV virus will remain a riddle given that infecting them just to validate the geneticist's claim amounts to a crime in itself.

"The Pandora's Box has been opened," wrote 122 Chinese scientists in a joint statement. For one, the experimentation is deemed unnecessary given China's mature technology to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding. On the other hand, using CRISPR-Cas9 (a technique allowing scientists to insert, deactivate, or replace a strand of DNA) to remove the CCR5 gene can help immunize humans from AIDS, smallpox and cholera, but it likely makes the body more susceptible to other viruses and illnesses, including cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, DNA changes will be bequeathed to future generations and likely change the whole human gene pool.

Many feared the experimentation would embolden eugenics and widened social gap as wealthier families can design their own babies. But there were supporters, who argued gene editing was no different than organ transplantation. And the U.S.' National Academy of Sciences early last year gave a cautious thumbs-up to genome editing of embryos to prevent serious diseases.

Humankind has tried to control nature at least since the beginning of agriculture, taming and breeding plants and animals to our liking. However, the ability to edit genes has presented us with a new conundrum, because the precision with which we alter our very selves – and even our identities – can start when we are unicellular. Is life written by science, or by us?

Read more: Genome Editing on Human Embryos

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3