Opinions

10:56, 01-Jun-2018

Opinion: Is 'The Art of the Deal' author a master of 'The Art of War'?

Tang Yinan

Editor's note: Tang Yinan is a research fellow at the China Institute of Fudan University. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

A specter is haunting the world, the specter of US trade hawks. By scrapping the trade truce and renewing tariff threats on May 29, the administration of President Donald Trump is not only moving against what it perceives as one of its greatest strategic rivals, but also mobilizing the masses and aligning their thinking with misplaced trade protectionism, which could spell disruption to the global economy. It is wise for China to consider the worst-case scenario in which the bilateral trade war eventually evolves into a strategic showdown.

It is important to note that the United States will make relentless efforts to suppress China from challenging its global supremacy, even though there’s a chance that Trump may take back his bellicose rhetoric on trade any minute, and the odds of the US winning the ongoing trade skirmishes are slim to none.

The key factor limiting the US' success is the scale of conflict. Had the current tussle between Beijing and Washington been much grander in scale, a more strong-willed United States would not hesitate to drop financial weapons on the trade battleground and make greater sacrifice in pursuit of ultimate strategic victory.

The terms brought up by US trade delegates in their negotiation with China reflect the US’s desire to confine China to its current role in the global division of labor and prevent the manufacturing giant from upgrading its technology. However, a reasoned desire for a strategic outcome may not prove to be tactically reasonable. When the US flaunted its strategic goal in a lesser affray, it helped China make a long-term decision to work towards scientific and technological self-reliance. In a recent meeting with China’s top science and engineering academicians, President Xi Jinping stressed the importance for key and core technologies to be "self-developed and controllable."

The current situation was created by the US when the Trump administration touted deficit reduction as a simple – though incorrect – way to restore trade balance, before it quickly stepped up demands for China to destroy its own technological future.

If "The Art of the Deal" author knew "The Art of War" better, he would probably heed Sun Tzu’s words of wisdom, "covering an unusual distance at a stretch, the leader of your army division will fall into the hands of the enemy."

Having failed to set executable goals for its long-term vision, the US revealed its strategic intention to China and was therefore flatly rejected.

But what if the US was well-prepared to wage a war against China on all fronts?

A key feature distinguishing post-WWII globalization from that of the previous era, in which colonial powers fought against each other to carve up the world, is that the new model centers on a hegemon who arbitrates global division of labor, which in turn determines the wealth of nations.

In both the former Eastern Bloc and the Western world, a member state’s role in the international division of labor had always been assigned by the pack’s alpha.

For example, when Japan and the US were embroiled in trade disputes in the 1980s, the US was in a position to discipline Japan: which sectors it could continue to develop and from which it must withdraw. That never was a trade war. After WWII, there was a time when Japan’s heavy industry base was largely obliterated by the US, and even now the Asian economic powerhouse still faces tremendous pressure from its ally in many high-end sectors such as aircraft manufacturing.

Until very recently, Japan had insisted on assembling military aircraft procured from the US despite the staggering cost of doing so domestically, so as to keep the industry alive.

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe during a news conference at the presidential palace in Bogota, Colombia July 29, 2014 ./VCG Photo

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe during a news conference at the presidential palace in Bogota, Colombia July 29, 2014 ./VCG Photo

China is not Japan.

Forged by fire, risen from blood, China’s autonomy in shaping its own industrial structure is the result of a series of hard-won victories, similar to those that empowered the US and the former USSR to shape other countries’ industrial structures. From the Opium War to 1949, semi-colonial China had been assigned the roles of an agricultural producer and a raw material provider. China was only able to defy such hegemonic arrangements after the Communist Party of China led the country to victory in both the Civil War and the Korean War.

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith gives a political economic definition of wealth, "wealth… is power.” Therefore, a nation’s position in the international division of labor is primarily a political issue, and only secondarily an economic and technological issue.

Based on its hegemonic experience, the US naturally feels itself in the right position to determine China’s place in the global division of labor. Besides, the US sees clearly the necessity of taking China down if it wants to prevent its own decline. However, the transfer of capital and industries from the US to China, and of consumer products from China to the US, is not the result of a US-dictated division of labor, but a coincidental outcome shaped by independent decisions from both sides.

Therefore, the political and economic setup between China and the US is heftier than what a hundred-billion-dollar trade war could shake up. No matter how the current trade dispute may end, the fundamentals will not change. But China has come to realize that the quest to "reach commanding heights in scientific and technological competition" requires much more than just commercial activities.

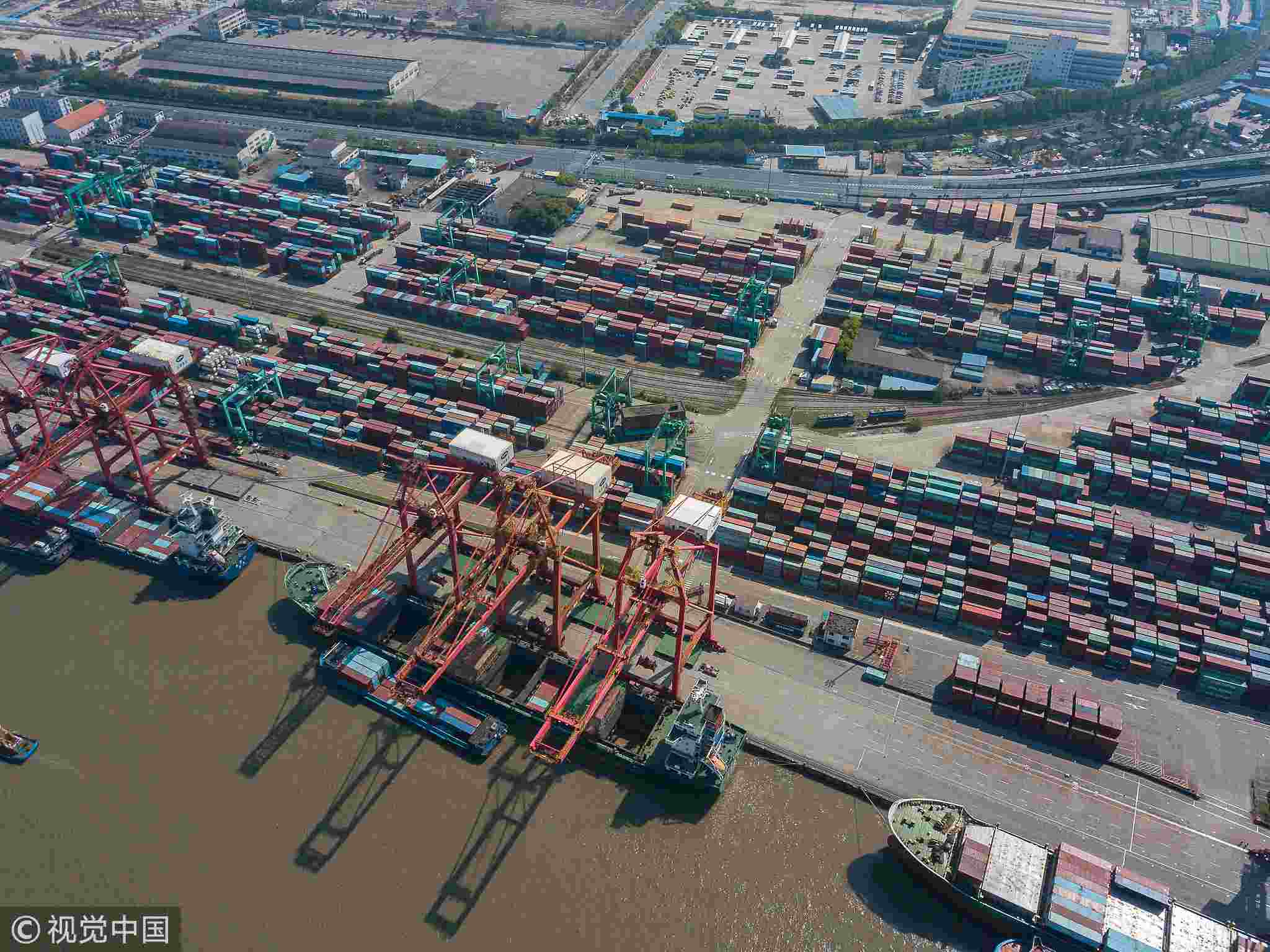

Aerial view of the port of Shanghai./VCG Photo

Aerial view of the port of Shanghai./VCG Photo

During the past National Memorial Day weekend, America put up a pageantry to commemorate the "forgotten" Korean War, underscoring its historical enmity towards China and openly fabricating allegations that China was responsible for waging the war. That is an indication that America has come to the realization that winning an all-out war against China is the only way for it to lay down the law.

China has no intention in playing America’s game, though it stands a good chance of winning it, because the cost will be immeasurable. However, facts on the ground suggest that the final showdown between China and the US may come one day even if the bilateral ties successfully endure the current trade conflict.

China has every interest in avoiding escalating a trade war into a financial war, because the US superpower lies in its foundation on finance, thus America’s financial sector enjoys absolute advantage over China's.

As an anti-China national consensus is beginning to take shape in the US, it is vitally important for those who are concerned with America’s future to understand the country’s resentful blame on China for its own decline is misplaced.

The fate of global economic system in the coming decades hinges on America’s attitude towards China.

While Americans are understandably anxious about losing their preeminence in the global division of labor, Trump is barking up the wrong tree by trying to reverse course on globalization – a hardly reversible process.

As for China, it is determined to uphold its industrial autonomy, but will never seek the power to dictate how other countries operate.

Will China’s vision of "a community of shared future for mankind" represent the next stage of globalization? It may well be. Such globalization should give every nation full autonomy in deciding its own future as a basis for international cooperation. China’s best hope for the enticing future is the US will not sabotage it.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3