False information may have always existed, but the buzzwords of 'fake news' are relatively new. It was not until the past four years that online misinformation, enabled by the rise of social media, became regarded as a real threat to society and world order. Governments, media and tech companies all agree now that something needs to be done, and soon.

This month, Singapore has joined a growing list of countries to introduce "anti-fake news" laws amid mounting criticism. The Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill (POFMA), set to take effect in the second half of this year, will give government officials the authority to determine what is false online.

The new law requires social media platforms to put up corrections alongside false information and threatens jail terms for serious offenders.

Legal experts, media and academia home and abroad have called the proposed law "far-reaching" and "disturbing." Rights groups fear that the law could be abused to limit free speech, with serious ramifications both in Singapore and around the world.

Singapore's government has said the law only deals with false statements of facts, not opinions, criticism, satire or parody. Only "those who profit from and peddle in falsehoods" need to be concerned, said the country's law minister.

Citing precedents in France, Germany and Australia, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong noted that Singapore is not the only country legislating on fake news at a press conference last week.

Singapore's prime minister Lee Hsien Loong speaks during a news conference with Malaysia Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in Putrajaya, Malaysia, April 9, 2019. /VCG Photo

Singapore's prime minister Lee Hsien Loong speaks during a news conference with Malaysia Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in Putrajaya, Malaysia, April 9, 2019. /VCG Photo

"The problem with fake news, of deliberate false statements being proliferated online is a serious problem which confronts many countries," Lee responded to media concerns after meeting with his Malaysian counterpart Mahathir Mohamad. Dr. Mahathir has made an election promise to scrap his country's fake news law enacted by the previous government.

While acknowledging at the same press conference that social media can be misused seriously, Dr. Mahathir reiterated his government's position: "When we have a law that prevents people from airing their views, we are afraid that the government itself may abuse the law like what has happened in the last government."

Singapore has been known for being heavy-handed with its laws on things like chewing gum and littering. But many netizens and younger Singaporeans have expressed shock and doubts about the new law.

"Singapore has a reputation of a nanny state, but this is carrying it too far," university student Alex Hoh said. He added that if all news were reliable, people wouldn't need to use their brains to assess information.

"Falsehood will always exist. It's superior to teach people how to think rather than what to think," Hoh said.

Commuters sit in front of an advertisement discouraging the dissemination of fake news, at a train station in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, March 28, 2018. /Reuters Photo

Commuters sit in front of an advertisement discouraging the dissemination of fake news, at a train station in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, March 28, 2018. /Reuters Photo

A global battle beset by controversy

Governments around the world have more immediate concerns, especially during key election campaigns. Fears of agenda-driven misinformation have taken the center stage of political discourse, as it is now understood that social media can be used to influence public opinions.

In the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election, followed by a high-profile and drawn-out investigation into alleged Russian meddling, many in the U.S. have attributed President Donald Trump's rise to false claims against his Democratic rival that went viral on social media sites like Facebook.

Ironically, it was Trump who has popularized the phrase "fake news" when he describes U.S. mainstream media's bias against his administration.

Speaking at a media forum in Dubai, Phil Chetwynd, Global News Director at AFP, which is part of Facebook's third-party fact-checking program, suggested that the global battle against misinformation began in 2016. "At this point, we realized the massive impact misinformation could have on global events," he said.

Many media professionals believe that fake news online has damaged public confidence in all news media.

A 2018 study by MIT published in Science magazine found that on Twitter, fake news spread six times faster and generate 70 percent more retweets than real stories.

Dozens of countries already have their versions of fake news law of varying severity. But over the past year, more western governments have defied public outcry to take regulatory actions against online misinformation.

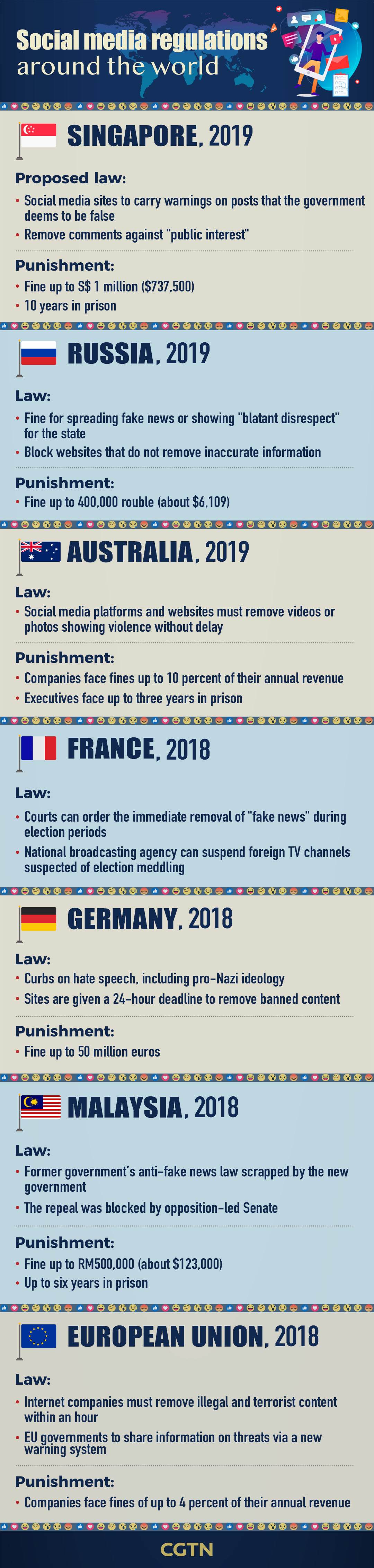

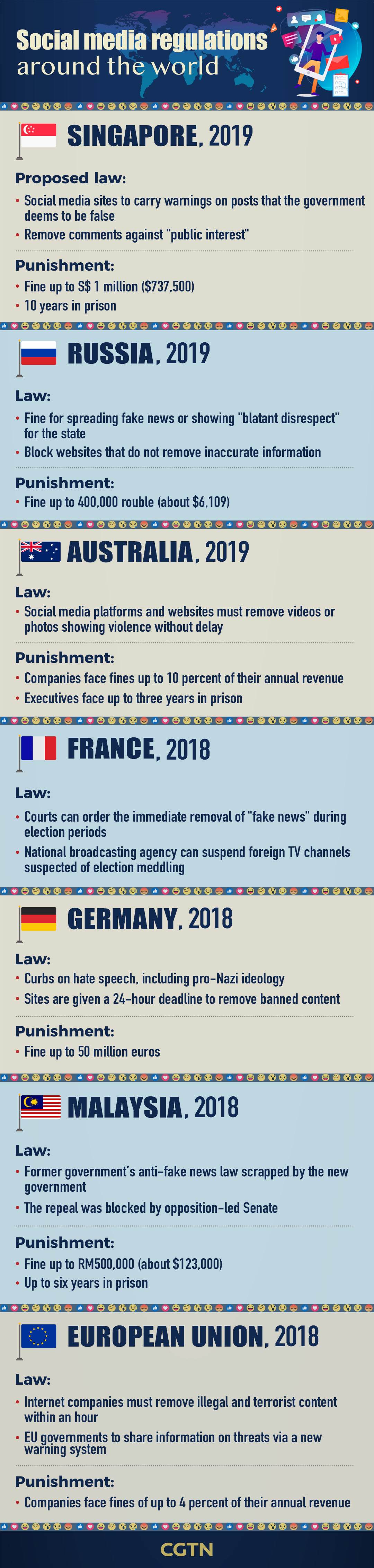

Social media regulations around the world in the past year. /CGTN Photo (Graphic by Fan Chenxiao)

Social media regulations around the world in the past year. /CGTN Photo (Graphic by Fan Chenxiao)

The overwhelming consensus has been that such laws should only apply to facts and not opinions. However, the governments of France and Germany have both come under scrutiny over perceived censorship, particularly when dealing with hot button issues like migration.

The majority of people are not good at distinguishing facts from opinions, as shown by a U.S.-focused study by the Pew center. This means even legitimate corrections online could be seen as a matter of different opinions.

The role of platforms and users

As social networks continue to break the barriers of publishing, a majority of news consumers (around 80 percent of Americans) support more regulations on social media. But this has created new problems for tech companies, which don't want to be seen as media, less so censors.

Tech giants such as Facebook were initially reluctant to regulate posts on their platforms, but have come under mounting pressure from authorities and public to do so.

Demonstrators in London protest against Facebook in the wake of revelations that the social media giant had been used to spread "fake news" in an effort to influence elections in Europe and the United States. /Reuters Photo

Demonstrators in London protest against Facebook in the wake of revelations that the social media giant had been used to spread "fake news" in an effort to influence elections in Europe and the United States. /Reuters Photo

Facebook has enlisted third-party fact-checkers to verify the accuracy of information posted on its platform, reducing viewer counts of content deemed to be false. This too has been dismissed by some political groups as censorship.

Some fact-checkers are said to face harassment and threats over their work as their decisions to flag posts have been seen as politically motivated.

Last year, Twitter blocked a voter registration campaign by the French government due to France's own anti-fake news laws, because the company wasn't sure what to do with political campaigns under the new laws in the country.

With tech companies taking much of the blame for the fake news problem, discussions have been mostly about how to manage online content with more regulations from top down.

But some experts argue that the role of information literacy is underestimated. And people's tendency to respond to information that confirms their own bias, resulting in an algorithm echo chamber, doesn't help.

Professor M. Laeeq Khan at Ohio University believes media and information literacy is vital to recognizing misinformation.

"Online users must possess an attitude of healthy skepticism when any information comes their way. Such an attitude of information verification by individuals can prove to be a major counterweight to the rising misinformation online," he said.