Opinions

17:40, 29-May-2018

Opinion: True springtime for Sino-Japanese relations?

Jia Xiudong

Editor's note: Jia Xiudong is a senior fellow at China Institute of International Studies CIIS. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Secretary-General of the Japanese ruling party Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Toshihiro Nikai arrived in China on May 25 for a five-day visit, his second in six months. The tour includes a trip back to Wenchuan, southwestern China's Sichuan Province, in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the massive Wenchuan earthquake.

Ten years ago, Nikai accompanied relief supplies from Japan to Sichuan after the earthquake. The ongoing visit is viewed in China as a goodwill gesture following a flurry of diplomatic exchanges between the two countries in the spring.

Nikai, regarded as the No. 2 political figure in the Japanese ruling party, next only to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, has been an active supporter of a close, constructive and cooperative relationship between China and Japan. He is a frequent visitor to China, either in his official or non-official capacity, often leading delegations with hundreds of or even thousands of members from various walks of life from Japan. His visits have been especially noteworthy when Sino-Japanese ties hit a low ebb in the past few years.

Toshihiro Nikai (R), secretary general of Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party, and Yoshihisa Inoue, secretary general of Komeito, the LDP's coalition partner, hold a press conference in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, on Dec. 26, 2017, after meeting with senior officials of the Communist Party of China. /VCG Photo

Toshihiro Nikai (R), secretary general of Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party, and Yoshihisa Inoue, secretary general of Komeito, the LDP's coalition partner, hold a press conference in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, on Dec. 26, 2017, after meeting with senior officials of the Communist Party of China. /VCG Photo

Since 2010, Sino-Japanese relations have remained bumpy due to three major irritants, namely the history, sovereignty, and security issues, and for many years Abe has made them worse since he assumed premiership in late 2012.

Abe’s visit to the Yasukuni Shrine honoring Class-A war criminals and continued beautification of Japan's aggression against its neighbors during the World War II soured China-Japan relations. The so-called “nationalization” of China’s Diaoyu Islands despite China’s strong protests, and Abe’s repeated refusal to acknowledge a long-held China-Japan consensus of shelving the dispute over the Diaoyu Islands and his attempt to strengthen the so-called administration of the Diaoyu Islands further chilled the bilateral relations.

Repeatedly the Abe administration labeled China as a major “security threat,” and used the “China threat theory” to justify its planned amendment of the pacifist constitution of Japan and a readjustment of its foreign and security policy in favor of a more strategically competitive stance towards China, leading to a higher trust deficit in China-Japan relations.

These political obstacles serve neither country’s interests and instead undermine their mutual interests in peace, stability and prosperity in the region. For example, the bilateral high-level economic dialogue experienced a hiatus of eight years, and the three-way cooperation between China, Japan and the Republic of Korea also suffered setbacks due to Japan’s poor handling of contentious historical and territorial issues.

In late 2014, after years of standoffs, China and Japan reached a four-point principled agreement on handling and improving the bilateral relations. This agreement led the two sides to reaffirmed the spirit of “facing history squarely and looking forward to the future.” acknowledged the existence of different positions between them regarding the tensions over the Diaoyu Islands, and agreed to prevent the situation from aggravating through resumed political, diplomatic and security dialogue.

The agreement offered a preliminary sign of a thaw in relations between the two countries. As a result, high-level exchanges have resumed, culminating in Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s official visit to Japan and his three-way summit with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and South Korean President Moon Jae-in in May this year.

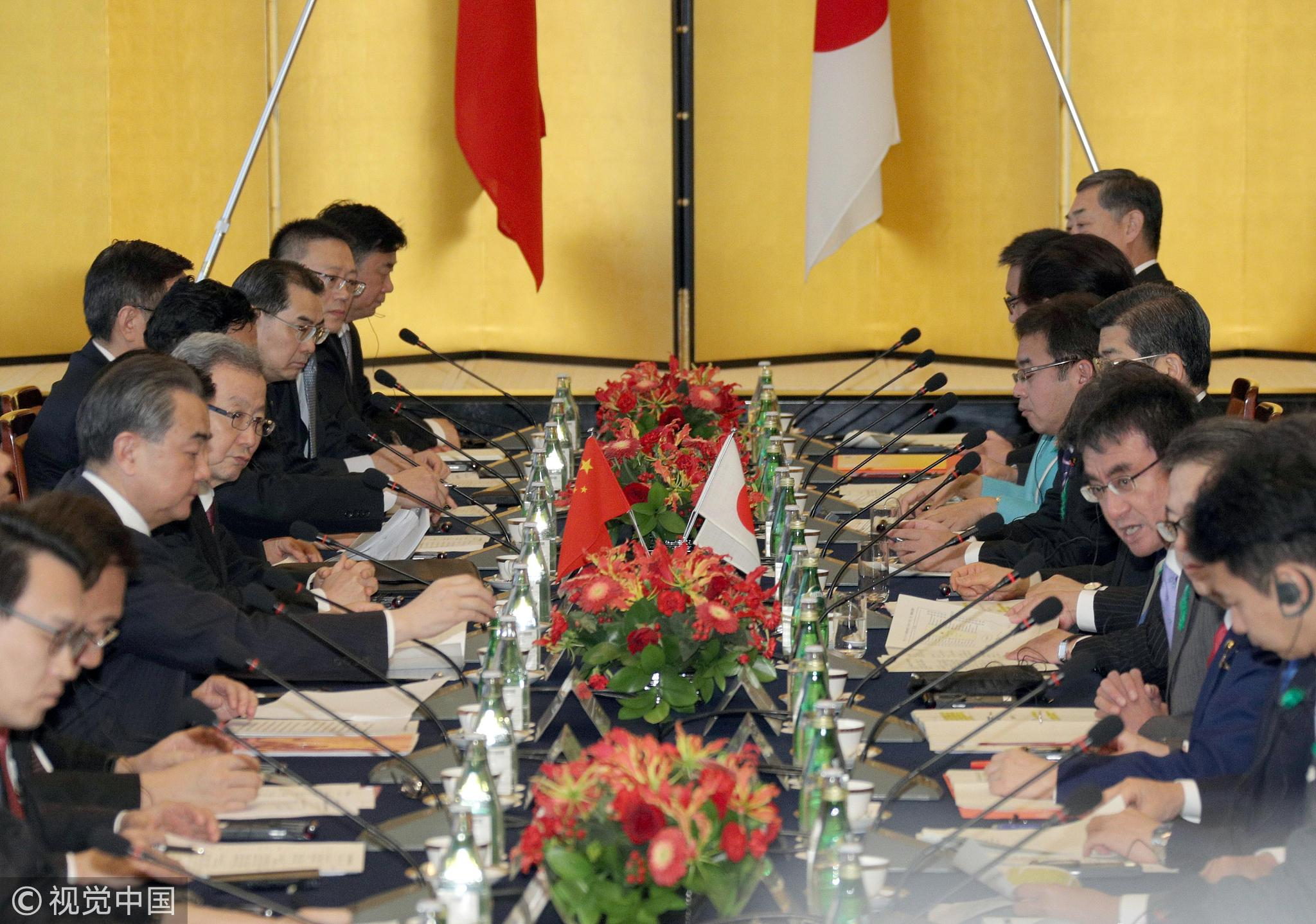

Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono (3rd from R) and Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (3rd from L) hold high-level economic talks at the Iikura Guest House in Tokyo on April 16, 2018. /VCG Photo

Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono (3rd from R) and Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (3rd from L) hold high-level economic talks at the Iikura Guest House in Tokyo on April 16, 2018. /VCG Photo

The fundamental reasons behind the improved relationship are two-fold.

First, over the past four decades, China and Japan have become increasingly intertwined and interdependent. They are important neighbors who have to live together and find common ground to get along with each other, ensuring that their differences and disputes be managed.

Even though Japan enjoys and values a strong alliance with the United States, it does not mean an either/or choice for Japan to make between China and the US. While Abe sticks with the centrality of Japanese alliance with the US and has tried consistently to build up rapport with President Trump, there are limits to the alliance and personal relationship, as shown in Japan’s failure to gain exemptions from Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs and to convince President Trump not to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal.

The Abe administration began to seek improving ties with its close geographical neighbors, especially China and South Korea, and to reconsider its policy on a trilateral free trade agreement (FTA) with China and South Korea and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

In addition, Japan has taken other steps to improve ties with China, including expression of interest in participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China.

Second, there remains a strong support in Japan for a sound and stable relationship with China as showcased by Mr. Toshihiro Nikai and his visiting delegation. The exchanges between political parties and politicians of the two countries as well as non-governmental exchanges have always been an important force for promoting the development of China-Japan relations.

Since the normalization of diplomatic relations between China and Japan 46 years ago, China-Japan relations have developed significantly with the joint efforts of insightful people from various circles in both countries. Many Japanese people are wary of Abe’s revisionist reading of history and efforts to amend the pacifist Constitution. They call for an improved relationship with China.

It is now safe to say that Sino-Japanese political ties are returning to normal. As 2018 marks the 40th anniversary of the signing of China-Japan Treaty of Peace and Friendship and both countries would like to shift their bilateral relations in a positive direction, the bilateral relations are facing new opportunities of development.

At the same time, some prominent challenges remain. While Abe may have changed his tone of rhetoric on China and his approaches to relations with China, fundamentals in his position have not changed.

As a right-leaning nationalist, Abe has formed a largely right-wing cabinet, encouraged right-wing political forces in Japan, and continued to pursue his dream to “make Japan strong again,” viewing China as a huge barrier to his dream. Mr. Toshihiro Nikai may serve as a bridge and messenger between Abe and Chinese leaders, but he and Abe are from different factions within the LDP, Nikai’s role in promoting China-Japan relations hinges to a large extent on Prime Minister Abe’s will and choice.

Twists and turns, ups and downs in China-Japan ties in the past caution against any rosy picturing of the bilateral relations, and at the same time substantial mutual interests of the two countries and shared aspirations of two peoples for peaceful coexistence and productive cooperation help sustain a reasonable expectation of the future bilateral relations.

The touchstone would be whether the Abe administration can adequately handle the history issue, refrain from provocations on the Diaoyu Islands and other issues hinging on China’s sovereignty, and continue to follow the path of peaceful development, abandon attempts to amend the pacifist constitution and adopt a prudent foreign and security policy towards China.

As is shown by China’s embrace of Mr. Nikai and his delegations, China is ready to work with Japan to bring the bilateral relations back to normal at an early date and make friendship prevail again in their relations. So long as Japan can join hands with China to do more to increase understanding, dispel mistrust and facilitate interactions between the two countries, and does not hesitate, backpedal or relapse, a true spring will come and be fruitful for the bilateral ties.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3