Animal

10:51, 26-Sep-2018

Ending decades of doubt, 'biggest bird' dispute put to nest

Updated

10:45, 29-Sep-2018

CGTN

After more than a century of conflicting evidence, Anglo-French animosity and a HG Wells novella involving murder most fowl, scientists said on Wednesday that they have finally solved the riddle of the world's largest bird.

For 60 million years, the colossal, flightless elephant bird – Aepyornis maximus – stalked the savannah and rainforests of Madagascar until it was hunted to extinction around 1,000 years ago.

In the 19th century, a new breed of buccaneering European zoologist obsessed over the creature, pillaging skeletons and fossilized eggs to prove they had discovered the biggest bird on Earth.

But a study released on Wednesday by British scientists suggests that one species of elephant bird was even larger than previously thought, with a specimen weighing an estimated 860 kilograms – about the same as a fully grown giraffe.

"They would have towered over people," James Hansford, lead author at the Zoological Society of London, told AFP. "They definitely couldn't fly as they couldn't have supported anywhere near their weight."

In the study, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, Hanson examined elephant bird bones found around the world, feeding their dimensions into a machine-learned algorithm to create a spread of expected animal sizes.

Until now, the largest-ever elephant bird was described in 1894 by the British scientist CW Andrews as Aepyornis titan – a larger species of Aepyornis maximus.

But a French rival of Andrews dismissed the discovery of titan as just an outsized maximus specimen, and for decades the debate remained deadlocked.

Hanson said his research proved titan was indeed a different species. But he also found that its bones were so distinct from other elephant bird specimens that titan was in fact an entirely separate genus.

Named Vorombe titan – Malagasy for "big bird" – the creature would have stood at least three meters tall, and had an average weight of 650 kilograms, making it the largest bird genus yet uncovered.

"At the extreme extent we found one bone that really pushed the limits of what we now understand about bird size," said Hanson, referring to the 860-kilogram specimen.

"And there were some that led up to that too, so it's not an outlier - there was a range of masses that are extraordinarily large."

Extinct, but not forgotten

A close cousin of the now-extinct moa in New Zealand, the elephant bird belonged to the same family of flightless animals that today includes the kiwi, emu and ostrich.

Brown Kiwi wandering in bush /VCG Photo

Brown Kiwi wandering in bush /VCG Photo

Its petrified eggs still fetch large sums at auction, and it stars in Wells' 1895 work "Aepyornis Island" alongside a pugnacious mercenary named Butcher who improbably ends up living with – and eventually killing – one of the creatures.

Despite having one of the longest existences of any animal in Madagascar – whose isolation from the rest of Africa led to the development of several entirely unique species – the elephant bird died out after a new wave of human settlers arrived around a millennia ago.

"You start to see large amounts of agricultural settlements and habitat change with burning of forests that seems to have driven all the megafauna in Madagascar, including the elephant bird, to extinction," said Hanson.

Far from being an ancient curiosity, Hanson believes the elephant bird could hold vital clues in how to manage Madagascar's future ecosystem, despite being extinct for 1,000 years.

Elephant birds "probably played the most significant roles in maintaining and developing the landscapes that were natural to Madagascar before humans got there," he said.

"We need to understand the role of these animals within these landscapes in order to start regenerating and conserving what we have left."

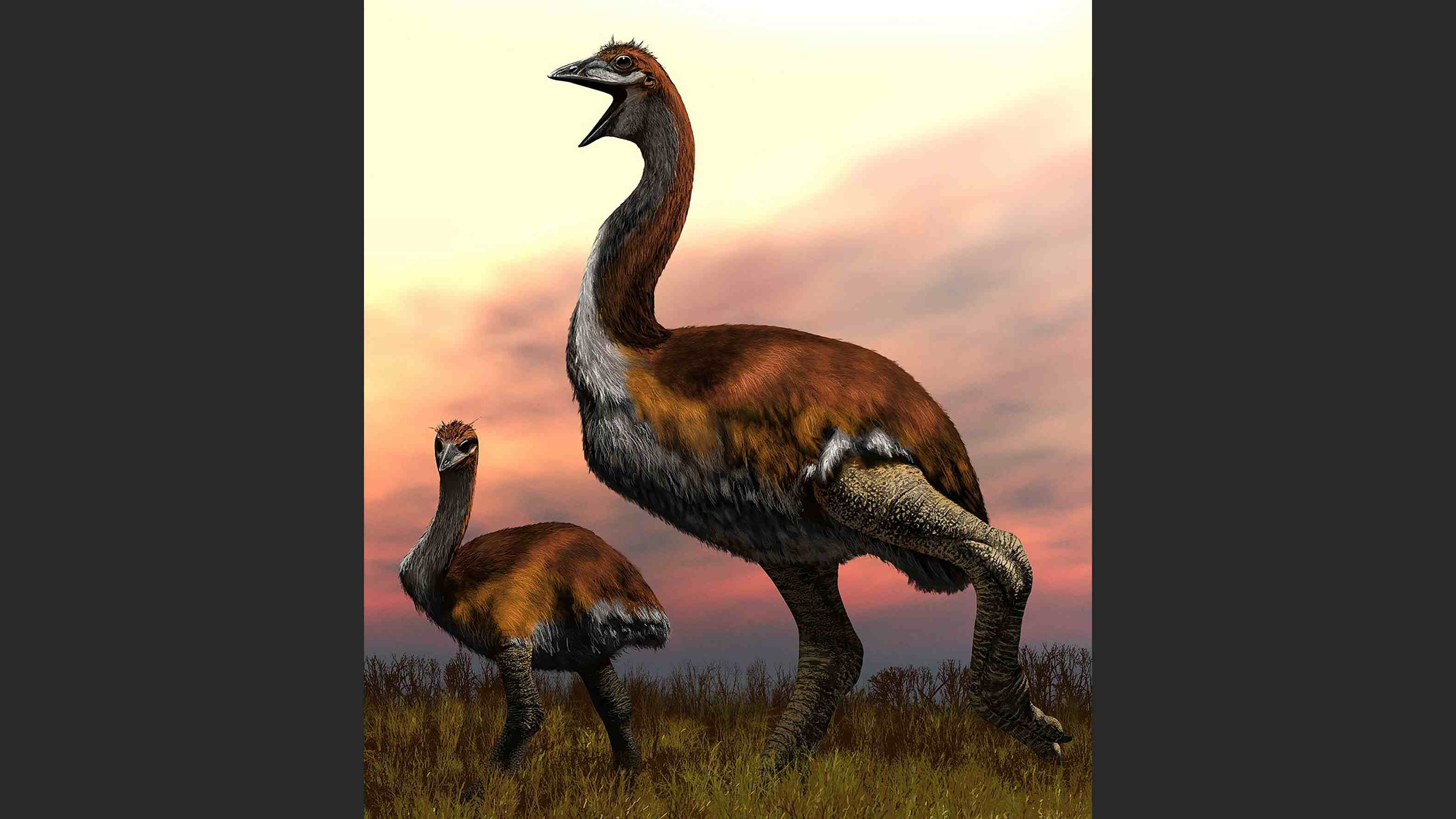

(Top image: An illustration of elephant birds /VCG Photo)

Source(s): AFP

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3