World

17:38, 27-Jul-2018

Japan executes sarin attack cult members

Updated

17:08, 30-Jul-2018

CGTN

Decades after the deadly 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, scores of people are still signing up to Aum Shinrikyo's successor groups each year, Japanese authorities say.

On Thursday, the last six members of the cult on death row were hanged over the attack that killed 13, just weeks after the group's near-blind "guru" Shoko Asahara was executed along with six other followers.

While the high-profile case served as a warning over the dangers of cults, the executions are unlikely to end the allure of such groups in Japan, said Kimiaki Nishida, professor of social psychology at Tokyo's Rissho University.

"We know that their followers didn't have a happy end," he said. "But I'm afraid cults will continue to exist, since society cannot solve every problem, while cults offer the fantasy that they have the answers to everything."

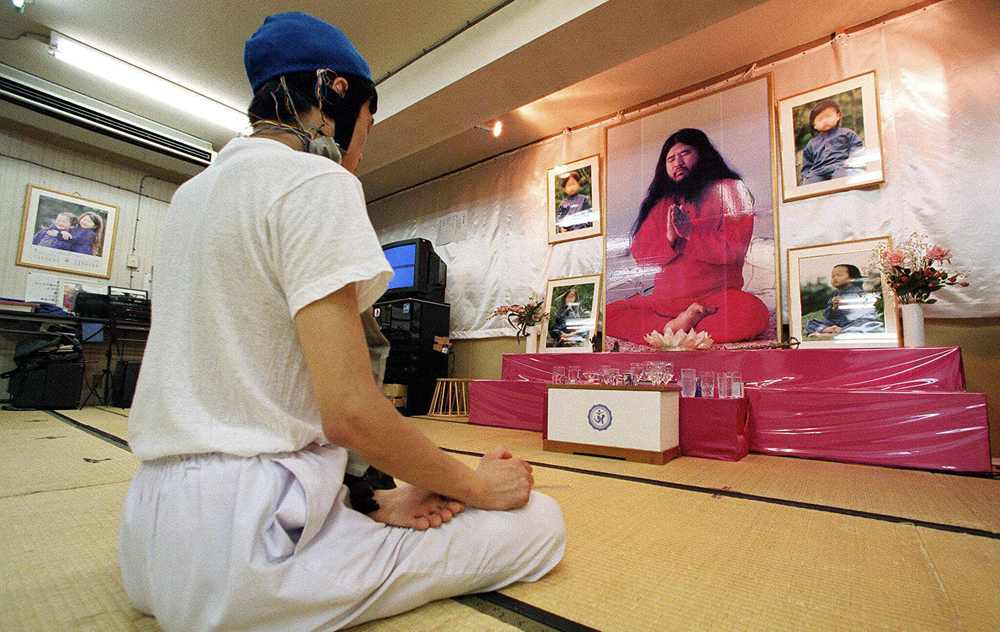

A follower meditates in front of portraits of Aum guru Shoko Asahara and his two sons on an altar at a seminary in Tokyo, August 11, 1999. /VCG Photo

A follower meditates in front of portraits of Aum guru Shoko Asahara and his two sons on an altar at a seminary in Tokyo, August 11, 1999. /VCG Photo

Aum successor groups have around 1,650 members in Japan, and hundreds more in Russia, according to Japan's Public Security Intelligence Agency.

It says the groups attract around 100 new followers a year through activities such as yoga and fortune-telling.

Unlike some European countries, where groups ranging from the Church of Scientology to the Unification Church are considered "cults," Japan takes a relatively open view towards what are often simply called "newly emerged religions."

Yoshiro Ito, an anti-cult lawyer, estimates tens of thousands of Japanese may belong to the Unification Church founded by late South Korean Sun Myung Moon, who is revered as a messiah by his followers.

Self-professed guru Asahara developed the Aum cult in the 1980s, attracting over 10,000 followers, including the doctors and engineers who manufactured the group's toxins.

The chemical weapons were deployed to devastating effect twice – in the Japanese city of Matsumoto in 1994, and then in 1995, targeting Tokyo's crowded subway system at rush hour.

The attack, which killed 13 people and left thousands injured, prompted a crackdown on the Aum's headquarters, where authorities discovered a plant capable of producing enough sarin to kill millions.

Escaped members of the cult and anti-cult activists had long warned about the Aum, but authorities had failed to act, and even after the sarin attack the group was not officially banned.

A commuter is treated at a make-shift shelter after being exposed to sarin gas fumes in the Tokyo subway system during an Aum sect attack, March 20, 1995. /VCG Photo

A commuter is treated at a make-shift shelter after being exposed to sarin gas fumes in the Tokyo subway system during an Aum sect attack, March 20, 1995. /VCG Photo

Two successor cults, Aleph and Hikarinowa, continue to recruit members and operate openly, which some experts say makes it easier to monitor them.

Aleph, which Asahara's wife and several children belong to, formally renounced the Aum guru in 2000. But he retained strong influence and some experts believe his execution may even boost his status.

Ito said Japan's complicated religious history had left many people unmoored from their faith and looking for answers.

"State sponsorship of Shintoism, with the emperor serving as a living god, was forced upon people during wartime. The US occupation forces broke it up," he said.

"Suddenly people didn't know what to believe."

Buddhism and Shintoism are the two major religions in Japan, but both faiths are falling out of favor.

"You used to have altars and home shrines in households, where you could feel you were connected to your ancestors," said Kenji Kawashima, professor of contemporary thought and philosophy at Tohoku Gakuin University.

"New religions have made inroads where traditions have been lost. Among them are radical ones, which are cults."

A focus in Japan on economic success, and immense pressure on young people, also increases the allure of fringe religious groups, Ito said.

"These youngsters are looking for warm hearts somewhere."

(Cover image: Pedestrians walk past a screen showing Shoko Asahara, leader of the Aum Shinrikyo cult, after the execution of six other members of the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult in Tokyo, July 26, 2018. /VCG Photo)

Source(s): AFP

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3