Opinion

20:42, 14-May-2019

Can Eurovision maintain its apolitical pretense in Israel?

Updated

21:50, 14-May-2019

Chris Deacon

Editor's note: Chris Deacon is a postgraduate researcher in politics and international relations at the University of London and previously worked as an international commercial lawyer. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Tuesday sees the first semi-final of this year's edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, with the second semi-final and grand final held later this week. The competition has always claimed to be apolitical and specifically bans performers from engaging in political acts. But this rule seems to be slowly eroding and, with the contest held in Israel this year, can Eurovision really claim not to be political any longer?

For those outside Europe who may not be familiar with Eurovision, the contest features vocal performances from multiple European (and some not so European) countries, with the winner decided by a mix of public and jury voting.

Held every year since 1956, the show is widely considered to be the world's most popular televised musical competition and draws audience figures of several hundred million. Despite predictions that it would lose popularity, it has consistently moved with the times and is as relevant as ever.

In fact, from this year, the first version of the contest for Asian countries will be held in Australia, such is the popularity of the format. Australia, interestingly, will then actually feature in both the regular Eurovision and the Asian spin-off as, since 2015, it has received guest status at the European contest.

One constant of the competition has been the position of its organizers – the European Broadcast Union (EBU) – that it is politically neutral, and any politicization of the contest is strictly prohibited.

This has always been a tenuous claim. The very nature of Eurovision – a competition between nations – has always given it a political edge. Indeed, the EBU has constantly felt the need to change the voting rules to try to avoid the inevitable patterns of friendly neighbors voting for each other regardless of quality.

It is de rigueur, for example, for Russia and Belarus to give each other high points. While the United Kingdom, failing to attract many votes at all in recent years, can usually always count on Ireland for a few points.

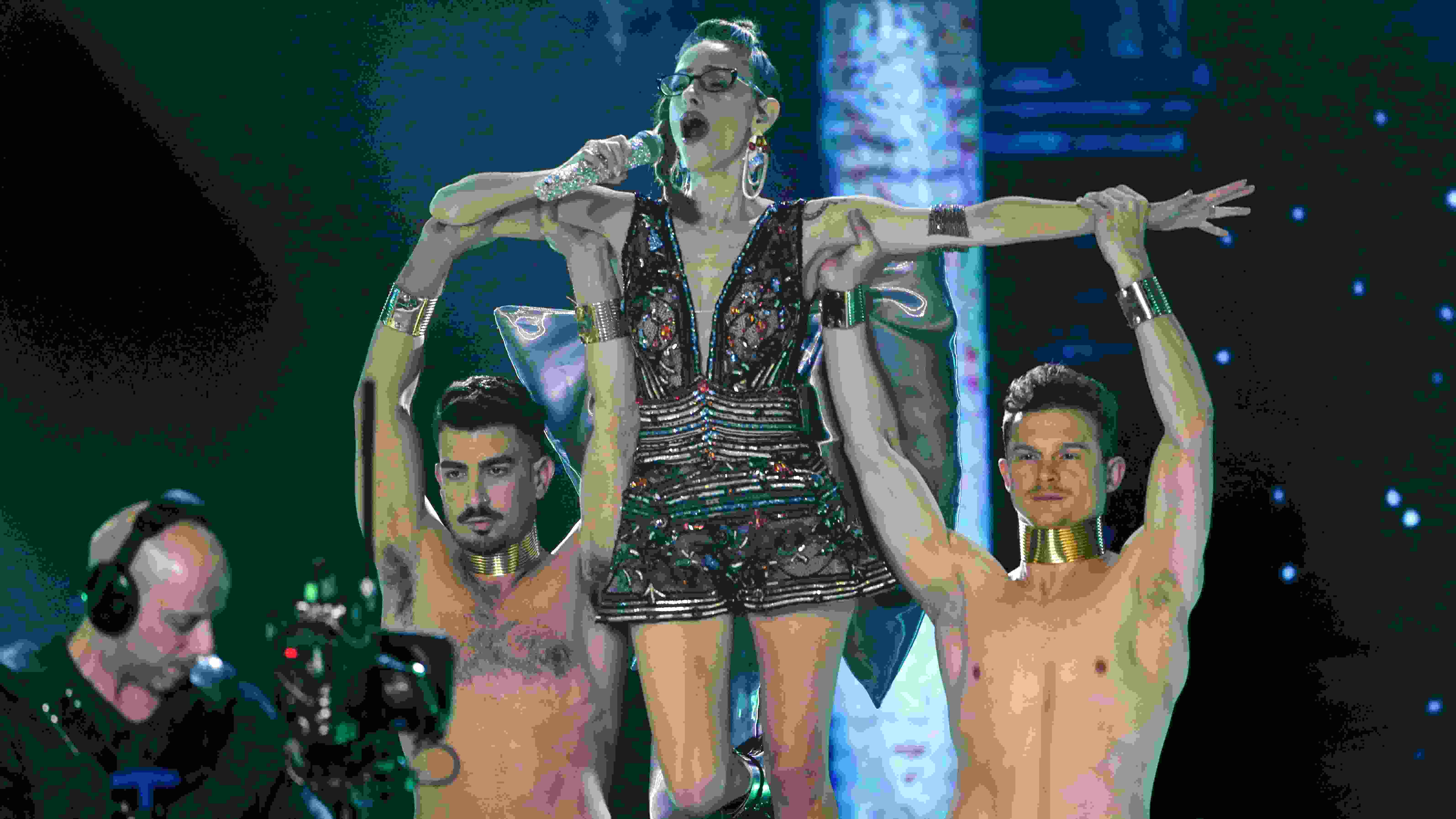

Israeli singer Shefita (Rotem Shefy) is singing in the reality TV show "The Next Star for Eurovision" in Neve Ilan, west of Jerusalem, February 12, 2019. /VCG Photo

Israeli singer Shefita (Rotem Shefy) is singing in the reality TV show "The Next Star for Eurovision" in Neve Ilan, west of Jerusalem, February 12, 2019. /VCG Photo

Such patterns have even seen the contest analyzed by scholars of politics and international relations to attempt to discern meaning from which countries are voting for which and what this says about the state of relations in the region.

But this background politicization has become more overt in recent years. In 2014, Austrian bearded drag act, Conchita Wurst, won the contest with a less than subtle statement about the treatment of sexual minorities across the region. Even more overtly, in 2016, Ukraine was victorious with the song "1944" – a confirmed allusion to the historical actions of Russia in the Crimea, attempting to echo more recent developments.

But when last year the Israeli contestant, Netta Barzilai, won the competition, the politicization of the whole event seemed inevitable. Eurovision is customarily held each year in the previous victor's country, so this year's contest is located in Tel Aviv. Calls for boycotts were immediately raised, showing the extent to which it is difficult for any event at all held in Israel to avoid politics.

No country has heeded the calls to boycott; however, a protest of a different kind is underfoot. This is without doubt the most interesting act this year and is performed by Iceland. The entry is sung by a "techno BDSM" band called Hatari, who claim to seek the overthrow of capitalism, and is titled "Hatrið Mun Sigra" – or "hatred will prevail."

It is a performance quite unlike anything Eurovision (and, perhaps, many Europeans) has ever seen and contains lyrics which tap into some of the darkest features of mankind, as well as predicting the collapse of Europe. Hatari have been open in their criticism of the Israeli government and have trod a fine line in presenting the song as a commentary on the situation in Israel and Palestine.

The EBU's decision to allow the performance without sanction appears to be a tacit admission that, while outwardly claiming that Eurovision is still apolitical, it has in fact always been political and is now more so than ever.

Given the precedent this sets, it may only be a matter of time before such political messages become widespread at the contest. One important way that Eurovision stays popular is by tapping into current trends and fashions, and politics can hardly be removed from this.

When Hatari perform in Tel Aviv this week, the overtly political statement they are making will be clear to all those watching. Eurovision is political now, if it ever was not, and that politicization is unlikely to go away any time soon.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3