Europe

16:44, 29-Mar-2019

The migrants and refugees stuck in Brexit limbo

Updated

21:13, 29-Mar-2019

Nilay Syam

The British government is bracing itself for one of the most ambitious and complex migration exercises ever undertaken in the country as European Union nationals scramble to protect their residency rights.

Around 3.5 to 4 million European Economic Area citizens are expected to apply under the EU Settlement Scheme (starting 30 March), in what may turn out to be a massive bureaucratic challenge for the authorities.

Settlement visas will be given to EU nationals who have resided continuously in the UK for five years. Those with less than five years' residence can apply for pre-settled status, which will be later converted into settled status.

The Home Office has assigned more than 1,500 caseworkers to the task and set a deadline of June 30, 2021, or December 31, 2020, if the UK leaves the bloc with no deal.

UK Prime Minister Theresa May on Wednesday pledged to step down if MPs back her EU divorce deal, London, March 27, 2019. /VCG Photo

UK Prime Minister Theresa May on Wednesday pledged to step down if MPs back her EU divorce deal, London, March 27, 2019. /VCG Photo

Caroline Nokes, the immigration minister who is supervising the scheme, assured applicants the process would be “easy and straightforward,” but concerns have been raised regarding the sheer volume of applications, which could potentially overwhelm the system.

Luna Williams, a political correspondent at Immigration Advice Service (IAS), said: “I am concerned that many EU nationals could miss the application deadline, be unaware that they need to apply, or not have the means to.”

She noted: “In the future, this could result in another Windrush, which saw thousands of legitimate citizens deported and threatened because they did not have official documents. There is a growing worry within our industry that the same could happen for EU nationals.”

Williams added that the UK leaving the EU without a deal would be the worst possible scenario since no immigration policies would be formalized.

“Although European temporary leave to remain has been promised, there is no real understanding of how this will be set up or monitored, trade will also be thrown into a dark area and this will impact immigration in many ways,” she said.

To complicate matters further, the UK Parliament's Joint Committee on Human Rights warned that EU citizens residing in the country could be stripped of freedom of movement, housing and social security rights by Home Office legislation introduced to regulate immigration post-Brexit.

The bill in its current form states that the rights of EU citizens living in the UK would be removed and reinstating them would rely on Home Secretary making secondary legislation.

Migrants, campaigners and activists gather in Parliament Square to celebrate the contributions of migrants to British society, February 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

Migrants, campaigners and activists gather in Parliament Square to celebrate the contributions of migrants to British society, February 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

Harriet Harman, a Labour Member of Parliament and chairwoman of the Joint Committee on Human Rights, said: “Human rights protections for EU citizens must not be stripped away after Brexit. EU citizens living in this country right now will be understandably anxious about their futures. We're talking about the rights of people who have resided in the UK for years, decades even, paying into our social security system or even having been born in the UK and lived here their whole lives.”

As Britain negotiates its exit from the EU, uncertainty over the fate of the country's immigration and refugee policy has been the subject of much consternation and debate.

Regaining control of the UK's borders was one of the defining arguments that united Eurosceptics and nationalists who voted to take the country out of the EU in the June 2016 referendum.

The exact contours of a post-Brexit strategy to tackle immigration remained vague until December 2018 when Prime Minister Theresa May's government produced a white paper.

Unveiling what he described as the biggest shake up of immigration policy for 40 years, Home Secretary Sajid Javid set out a new points-based system that would kick in from 2021.

Javid said, while there was no “specific target” for reducing numbers coming into the country, net migration would come down to “sustainable levels.”

The new rules proposed by the government include:

• Scrapping the current restriction on the number of skilled workers from the EU and rest of the world.

• A salary threshold of 30,000 British pounds (46,000 U.S. dollars) for skilled migrants seeking five-year visas, pending further consultation.

• Allowing lower-skilled migrants to stay and work for up to a year until 2025.

• Granting visa-free entry to visitors from the EU.

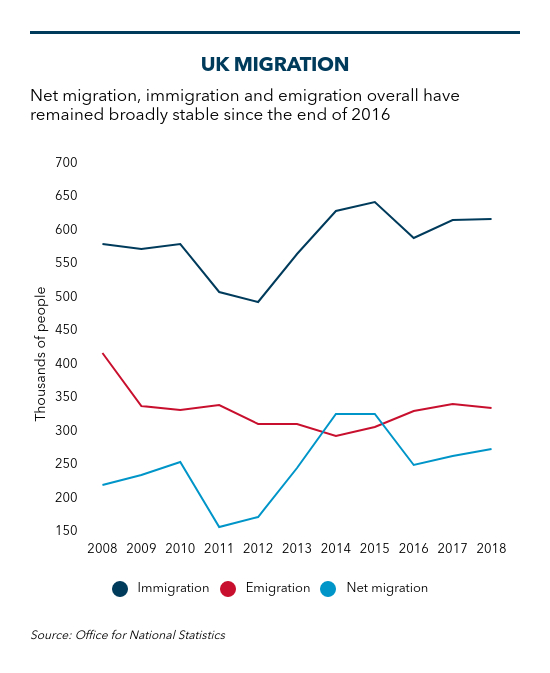

UK migration. /CGTN Photo

UK migration. /CGTN Photo

To help would-be migrants apply in good time, visa applications would be accepted from autumn 2020, provided the UK does not crash out of the EU without a deal.

The white paper was followed by a report from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in February, which showed net migration to the UK from countries outside the EU hitting its highest levels in 15 years.

According to the ONS, 261,000 more non-EU citizens entered the country than exited in the year ending September 2018, the highest since 2004.

In contrast, migration from EU nations continued to drop to a level last seen in 2009.

Separate figures released by the Home Office show the number of EU nationals applying for British citizenship rose to an all-time high in 2018, spiking by 23 percent to about 48,000.

Apart from the status of economic migrants, there is anxiety about what awaits refugees and asylum seekers in post-Brexit Britain.

Advocacy groups have raised the specter of more restrictive policies and therefore potentially fewer refugees being admitted to the country.

Trouble ahead: storm clouds are gathering for migrants in the UK. /VCG Photo

Trouble ahead: storm clouds are gathering for migrants in the UK. /VCG Photo

However, the UK continues to remain committed to obligations under international human rights laws and a party to the UN Refugee Convention, which sets out the rights of individuals who are granted asylum and the responsibilities of nations that grant permission to resettle.

Official figures reveal Britain offered protection, in the form of asylum and other alternative forms of resettlement, to 15,891 people in 2018.

The Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS) accounted for three-quarters of the 5,806 refugees resettled in the UK last year. Since its launch in 2014, 14,945 people have now been resettled under VPRS. An additional 688 were resettled under the Vulnerable Children Resettlement Scheme (VCRS).

Britain received 29,380 asylum applications in 2018, 11 percent more than the previous year, although it is lower than levels witnessed in 2015 and 2016 during the European migration crisis.

Matthew Rodgers, from ACH, a social enterprise that works to resettle refugees, said: “Numbers are unlikely to be affected. The UK already had more flexibility than other EU members, allowing it to opt in or out of EU policies on migrants and refugees, keeping the number of asylum seekers arriving in Britain relatively low. That will not change.”

An anti-Brexit, pro-Europe demonstrator in Westminster, March 26, 2019. /VCG Photo

An anti-Brexit, pro-Europe demonstrator in Westminster, March 26, 2019. /VCG Photo

He added: “Any effects on migration from outside the EU and asylum after Brexit are likely to be indirect, as a result of the changed political environment within the UK. Asylum numbers are already extremely low compared with the rest of Europe.”

In 2015, former Prime Minister David Cameron pledged to resettle people from outside the EU as part of the UNHCR Resettlement Program, including 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2020. The government in 2016 promised to further resettle individuals considered at risk, particularly children. Rodgers said these pledges will be unaffected by Brexit.

Some activists, however, predict a rise in asylum applications once Britain leaves the EU since it will no longer be party to the Dublin Regulation, an EU law that determines which member state is responsible for examining asylum applications.

As per the Dublin rules, an asylum seeker may be legally returned to the first EU country where they arrived. The UK has claimed to take “full advantage” of the regulation to stem the ingress of refugees. This can change after Brexit with the Home Office having to receive and process individual asylum claims, since the option to return applicants to Europe will no longer exist.

(Patrick O'Donnel also contributes to this story.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3