Editor's note: Ji Xianbai is a doctoral candidate from S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) enters into force today. The world's third largest regional trade bloc and one of the least geographically-bound free trade agreements (FTAs), the CPTPP involves 11 countries around the Pacific Rim (Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam) whose combined economies represent more than 13 percent of global total economic output.

Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, and Singapore will implement the first round of tariff liberalization today, and they (except Japan) will proceed to carry out the second round of tariff cuts on January 1, 2019.

It is expected that Chile and Peru will soon complete domestic legislative procedures to approve the CPTPP so as to benefit from the deal.

My estimates, using an advanced general equilibrium model, suggest that Malaysia, Vietnam, Brunei, and New Zealand will see their national real gross domestic product grow by more than 1 percent in the medium run.

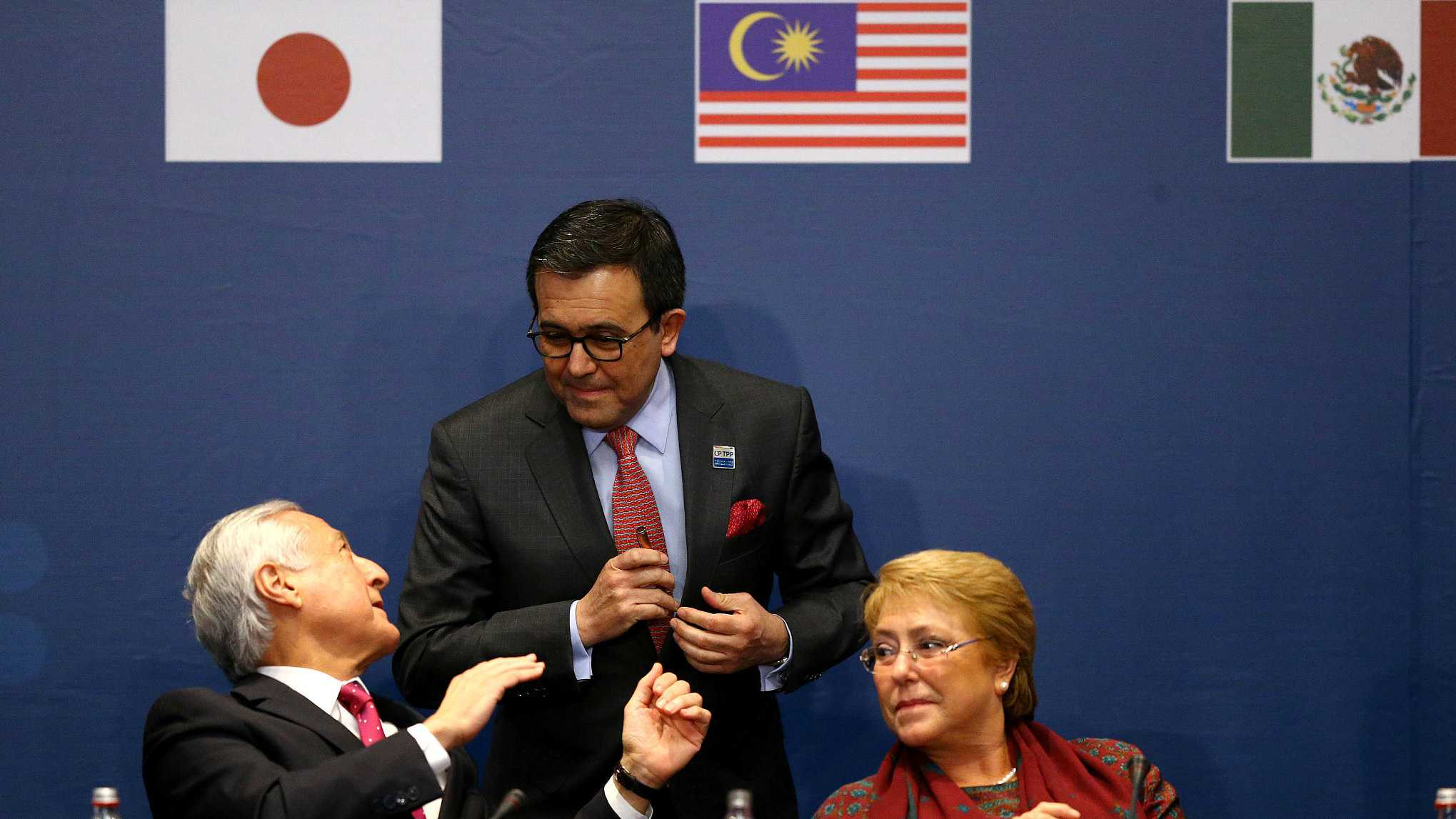

Leaders pose for an official picture after signing the rebranded 11-nation Pacific trade pact Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in Santiago, Chile, on March 8, 2018. A slimmed-down trade pact signed on Thursday will allow eleven Asia-Pacific nations to push forward with economic integration in the face of greater US protectionism, even if the new deal will offer less benefits than originally hoped. /VCG Photo

Leaders pose for an official picture after signing the rebranded 11-nation Pacific trade pact Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in Santiago, Chile, on March 8, 2018. A slimmed-down trade pact signed on Thursday will allow eleven Asia-Pacific nations to push forward with economic integration in the face of greater US protectionism, even if the new deal will offer less benefits than originally hoped. /VCG Photo

Export volumes of Malaysia, Vietnam, New Zealand, and Australia would also expand greatly thanks to the CPTPP. Japan stands out as the largest beneficiary under the CPTPP with respect to welfare gains.

A deal two decades in the making

For all these potential economic benefits, it is important to recall that this landmark trade deal has traveled a tumultuous journey in the past two decades. And interestingly, it has been known by different acronyms at different points in time.

In late 1998, when the early voluntary sectoral liberalization scheme under the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) hit a roadblock, the United States floated the idea of a Pacific-5 (P5) FTA including Australia, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore with an eye to sustaining the trade liberalization momentum in APEC. The P5 FTA did not materialize eventually because the United States and Australia pulled back from the project for various domestic reasons.

Nevertheless, the flame of the P5 FTA was kept alive by Singapore, Chile and New Zealand. They in conjunction with Brunei reached the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPSEP) in 2005.

As the P4 countries were about to negotiate the outstanding Financial Services and Investment chapters in 2008, the United States joined the talks. America's participation was quickly followed by those of Australia, Peru and Vietnam. Thereafter, Malaysia, Canada, Mexico, and Japan joined the talks one after another, bringing the total number of partners to 12. The TPP12 agreement was concluded and signed in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

The original TPP12 never took effect due to the withdrawal of the United States by President Trump in early 2017. After a short period of confusion, the remaining 11 countries soldiered on and signed a revamped agreement, the CPTPP or TPP11, in March 2018 to move ahead with trade liberalization without the United States.

CPTPP's history attests to the fact that the deal is extremely resilient despite changing policy environments and remarkably fluid in terms of membership composition. As it goes into effect formally, more countries have lined up for CPTPP membership.

Toshimitsu Motegi, Japan's minister in charge of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, signs the revised free trade pact in Santiago, Chile, on March 8, 2018. /VCG Photo

Toshimitsu Motegi, Japan's minister in charge of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, signs the revised free trade pact in Santiago, Chile, on March 8, 2018. /VCG Photo

Who could be potential new members?

Potential new members include South Korea, Thailand, Columbia, Ecuador, and the Philippines. A somewhat unexpected CPTPP candidate country is the Brexiting Britain. The country looks set to leave the European Union in March 2019 and is in need of new commercial ties with fast-growing markets in the Asia-Pacific region to reduce the economic pains of leaving the European Single Market.

Describing the CPTPP as a “force for good” in buttressing a rules-based trade order, the UK has already initiated informal consultations with incumbent members. Political support for the UK's CPTPP accession is also high in the grouping with the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe saying in October that the post-Brexit UK would be welcomed into the agreement “with open arms.”

Because China is unlikely to join the CPTPP anytime soon, it will inevitably suffer from a certain degree of trade diversion as the 11 signatories open their markets reciprocally.

The most effective response to mitigate the potential economic losses and more broadly to the evolving global trade landscape in flux, especially against the background of the Sino-American trade war, is to conclude the ongoing negotiations for the 16-party Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) as soon as possible.

The trade creating benefits of RCEP would offset the trade diversionary effects stemming from CPTPP exclusion. China's dominant position in RCEP talks would also ensure the emerging rules governing 21st century trade-service-investment nexus to be consistent with Chinese interests, values, preferences, and practices.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)