Not unexpectedly, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan claimed outright victory in the presidential elections after securing over half of the votes cast on Sunday.

Daunting tasks such as improving the economy and people's livelihood are awaiting the leader, but another interesting aspect that is worth keeping an eye on is how Erdogan will approach his country's foreign policy in the post-election era, particularly after promising in his election manifesto to build Turkey into a global power.

With a foot in Asia and another in Europe, Turkey has a natural geopolitical significance. Making the Republic of Turkey, the predecessor of the Ottoman Empire, great again is arguably the common aspiration of Turkish leaders, particularly the one who just won five more years in office.

June 24, 2018: Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan waves to supporters gathered at the headquarters of the AK Party to celebrate Erdogan's victory in the election, in Ankara, Turkey. /VCG Photo

June 24, 2018: Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan waves to supporters gathered at the headquarters of the AK Party to celebrate Erdogan's victory in the election, in Ankara, Turkey. /VCG Photo

So how might Turkey, under Erdogan's presidency, maneuver its ties with major players to increase its relevance in the international arena?

US: an indispensable but hard-won alliance

The relations between Turkey and the US, its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), have been bumpy in recent years. Tensions have risen over the US' support of Kurdish fighters in Syria, whom Turkey sees as an extension of the banned Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). Washington says its move helps fight off ISIL, while Ankara says it is a way of strengthening the hand of whom the Turkish leadership calls Kurdish "terrorists."

Ties particularly strained during the aftermath of

a failed coup in Turkey in July 2016, when Erdogan embarked on a large-scale arrest spree of military officials, university teachers and journalists – whom he suspected were behind the putsch, drawing strong criticism from the US over concerns of a crackdown on dissent.

April 30, 2015: Foreign fighters who joined the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) to fight in their ranks against jihadists and Islamist rebels in northeastern Syria take part in a training session. /VCG Photo

April 30, 2015: Foreign fighters who joined the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) to fight in their ranks against jihadists and Islamist rebels in northeastern Syria take part in a training session. /VCG Photo

Turkey, on the other hand, has repeatedly denounced the US over its unwillingness to extradite Fethullah Gulen, a Turkish cleric in self-imposed exile in the US and who Erdogan believes plotted the coup.

However, despite the resentment and grudge, the Turkish government is very likely to seek a better alliance with the US after the election. As Erdogan’s ruling AK Party’s election manifesto states: “It is essential to maintain close cooperation with the US.”

There is too much at stake for the pair as their paths are intertwined in so many current affairs like Syria, terrorism, Russia and Europe's security.

September 21, 2017: US President Donald Trump reaches to shake Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's hand before a meeting at the Palace Hotel during the 72nd United Nations General Assembly in New York, the US. /VCG Photo

September 21, 2017: US President Donald Trump reaches to shake Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's hand before a meeting at the Palace Hotel during the 72nd United Nations General Assembly in New York, the US. /VCG Photo

To which extent tensions could ease still bears a big question mark. As revealed in the manifesto, Erdogan’s government will base its cooperation on “three specific demands,” namely the cessation of the US support of the YPG – the Kurdish fighters in Syria, support of Turkey in dealing with the PKK, and handing over Fethullah Gulen.

It remains to be seen how the US would deal with these demands.

EU: Patience is the key

Turkey’s decades-long attempt to join the European Union is arduous. Compared with its NATO membership which took effect as early as 1952, talks about its joining the EU have been excruciatingly long, dragging on since 2005.

Recently the talks have come to a temporary halt due to European concerns over the situation of human rights and the rule of law in Turkey, after the 2016 coup.

July 7, 2017: German Chancellor Angela Merkel (L) stands next to Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan as he arrives to attend the G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany. /VCG Photo

July 7, 2017: German Chancellor Angela Merkel (L) stands next to Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan as he arrives to attend the G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany. /VCG Photo

Despite the future of an EU membership seeming gloomy, Turkey is not ready to call it quits. In March, Erdogan said his country still seeks to gain a "full membership" in the EU, which was echoed again in his election manifesto.

For Ankara, improved ties with the European bloc entail huge potentials in trade and economy. The EU is Turkey's number one import and export partner. Meanwhile, the visa-free policy among most EU members also appeals strongly to the Turkish government, which is eager to fight for the same benefit for its people.

Protesters shout slogans on a police bus after they were detained by riot police during the trial of two Turkish teachers, who went on a hunger strike over their dismissal under a government decree following the 2016 failed coup, outside of a courthouse in Ankara, Turkey, September 14, 2017. /VCG Photo

Protesters shout slogans on a police bus after they were detained by riot police during the trial of two Turkish teachers, who went on a hunger strike over their dismissal under a government decree following the 2016 failed coup, outside of a courthouse in Ankara, Turkey, September 14, 2017. /VCG Photo

But the current lukewarm attitude from the leaders of major EU countries doesn’t bode well for Turkey's aspiration. To regain their interest, one step might be the removal of the state of emergency inside Turkey.

While that may or may not happen soon, one thing for sure is that Turkey has, or has to have, patience with its EU partners, in pursuit of the much-awaited long-yearned-for accession.

Mideast neighbors: as complicated as forever

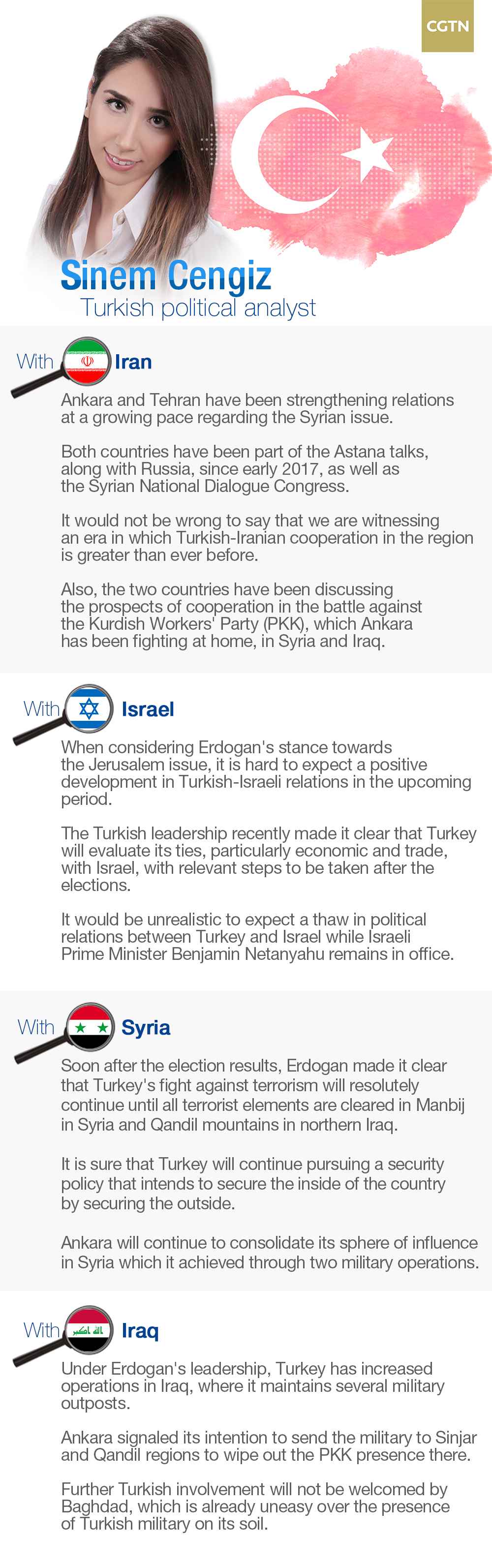

In an email interview with CGTN Digital, Sinem Cengiz, a Turkish political analyst who specializes in Turkey's relations with the Middle East, weighed in on the possible development of ties between Turkey and its key neighbors in the region:

Pragmatic cooperation with China

The Sino-Turkish relations have generally been on an upward trajectory in the past ten years or so since bilateral ties were elevated to the level of "strategic cooperation" in 2010.

Many wonder whether Turkey will drastically shift its strategic orientation from the West to the East, against the backdrop of an all-time low relationship with its Western partners.

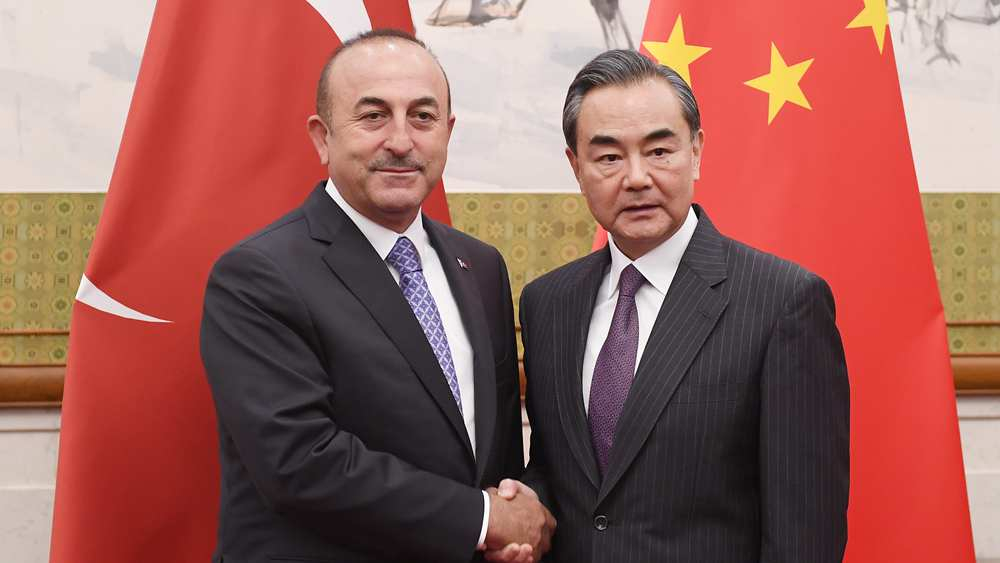

June 15, 2018: Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu (L) shakes hands with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi before a meeting in Beijing, China. /VCG Photo

June 15, 2018: Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu (L) shakes hands with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi before a meeting in Beijing, China. /VCG Photo

That speculation seems unlikely as Turkey itself, or rather, Erdogan's government already vowed to keep its goal of joining the EU alive, and called for warmer ties with the US. Nevertheless, it doesn't contradict Turkey's work to further cooperate with China on economic and trade fronts.

An opinion piece by Selçuk Colakoglu, director of the Ankara-based USAK Center for Asia-Pacific Studies, cited figures from the Turkish Statistical Institute showing the importance of ties between China and Turkey. Bilateral trade rose to 27.8 billion US dollars in 2016, and reached 21.66 billion US dollars in the first 10 months of 2017.

May 16, 2018: People visit a booth that promotes the 2018 Turkish Tourism Year at the ITB China 2018 Trade Fair in Shanghai, China. /VCG Photo

May 16, 2018: People visit a booth that promotes the 2018 Turkish Tourism Year at the ITB China 2018 Trade Fair in Shanghai, China. /VCG Photo

Adding to that, the China-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are two projects that will offer unprecedented opportunities for Turkey to benefit from, as long as it maintains an active participation.

Russia: friend or foe?

The relations between Turkey and Russia took a turn for the worse in 2015, when the

former shot down a Russian air force jet carrying out missions in Syria. Following the incident, Russia imposed a host of sanctions on Turkey, seriously hurting Turkey's economy, particularly the tourism industry.

But the soured ties made a surprising turnaround in the aftermath of the failed coup in Turkey in 2016, when Erdogan held out an olive branch and wrote to President Vladimir Putin to apologize for the jet downing.

November 30, 2015: The coffin of the pilot killed when Turkey shot down a Russian jet is carried out of a military hospital morgue by Turkish soldiers for its transfer to Esenboga Airport in Ankara, Turkey. /VCG Photo

November 30, 2015: The coffin of the pilot killed when Turkey shot down a Russian jet is carried out of a military hospital morgue by Turkish soldiers for its transfer to Esenboga Airport in Ankara, Turkey. /VCG Photo

Russia, in response, showed reciprocal amity by gradually lifting most sanctions off Turkey by mid-2017.

The two countries, together with Iran, have been trying to broker a political solution to the Syrian conflict through peace talks that began in the Kazakh capital Astana in 2016.

However, some observers believe that the cordial interaction between the two is not as steady as it looks. The Straits Times quoted Dr. Alexey Malashenko, a specialist on the Syria conflict, as saying that Russia, Turkey and Iran have a "very shaky" alliance.

March 16, 2018: Turkish Foreign Affairs Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu (R) shakes hands with President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev (L) as they are flanked by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (2nd R) and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (2nd L) after the ninth round of Syria peace talks in Astana, Kazakhstan.

March 16, 2018: Turkish Foreign Affairs Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu (R) shakes hands with President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev (L) as they are flanked by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (2nd R) and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (2nd L) after the ninth round of Syria peace talks in Astana, Kazakhstan.

The different intentions among the three countries regarding Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his government's future are also likely to tear up the coalition.

More importantly, Turkey's closer ties with Russia may risk further alienating itself from the EU and the US. Therefore, it is still not the time to decide whether Turkey and Russia will always be on friendly terms.

The word "frenemies" may be a better description and prediction of the pair's status in the long run.