Opinion

16:56, 23-Mar-2019

China's open-door policy continues to unwind

Updated

11:49, 24-Mar-2019

Liu Baocheng

Editor's note: Liu Baocheng is a director of the Center for International Business Ethics at the University of International Business and Economics. The article reflects the view of the author, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

The 2019 China Development Forum is currently underway in Beijing with the theme focusing on a further opening-up of the country's economy.

According to Chinese Commerce Minister Zhong Shan, foreign direct investment (FDI) into China rose by 3 percent year-on-year to 135 billion U.S. dollars in 2018, which marks a significant slowdown from 7.9 percent in 2017.

Does this imply that China is getting wary of foreign investment? This is juxtaposed with a steep decline of outbound direct investment (ODI) in North America and Europe by Chinese firms from 110 billion U.S. dollars to a mere 30 billion U.S. dollars during the same period. Does this mean China is reversing its “going abroad” policy?

Until recently, doubts have loomed large as to whether China has lost the momentum to further open its market and continue with its reform agenda against the backdrop of anti-globalization and populism.

Nonetheless, the approval of the Foreign Investment Law by the country's top legislature – the National People's Congress (NPC) – in March 2019 helps to disperse much of the hanging clouds.

Foreign Investment Law. /VCG Photo

Foreign Investment Law. /VCG Photo

The law, which aims to create a fair and transparent business environment to provide an equal level playing field for foreign and domestic firms, has consolidated three preexisting regulations, namely, the Foreign Enterprise Law, China-Foreign Equity Joint Venture Law and China-Foreign Contractual Operation Law.

In addition to the streamlined legal framework, it offers improved protection of intellectual property rights by forbidding forced technology transfer, promises equal pre-establishment treatment and equal access to government procurement, and sanctions the negative list for all types of foreign companies.

As a matter of fact, China has still managed to stand out in its FDI inflow with a positive figure as the world's second largest recipient in spite of the decrease compared to last year. And multiple factors have contributed to the drop of ODI from China, such as China's past policies to control capital flight and the duplicitous national security review in the U.S.

China's road to more openness

Notwithstanding its substantial improvement, the new Foreign Investment Law has not completely removed distrust among critics.

Questions raised include: 1) When certain provisions remain vague, is it deliberately leaving space for subsequent free interpretation, with the stipulation of national security review in particular? 2) Is China going to seriously enforce this law or simply use it as an instrument of expediency in response to U.S. pressure?

To address these concerns, a host of related regulations are already under stringent review, while Chinese lawmakers are actively engaged in drafting more elaborate implementation measures.

In fact, this law has been in the making since 2015 which is way ahead of the start of the China-U.S. trade war. As for the question of China's commitment to this law, nothing is more convincing than to answer whether it is there to serve the fundamental and sustainable interest of China.

China knows very well that no single country can climb on to the ladder of innovation without proper IP protection, and that no foreign investment can park long in a precarious regime under a whimsical legal environment.

A large-scale variety show celebrating the 40th anniversary of China's reform and opening-up policy is held in Shenzhen, September 20, 2018. /VCG Photo

A large-scale variety show celebrating the 40th anniversary of China's reform and opening-up policy is held in Shenzhen, September 20, 2018. /VCG Photo

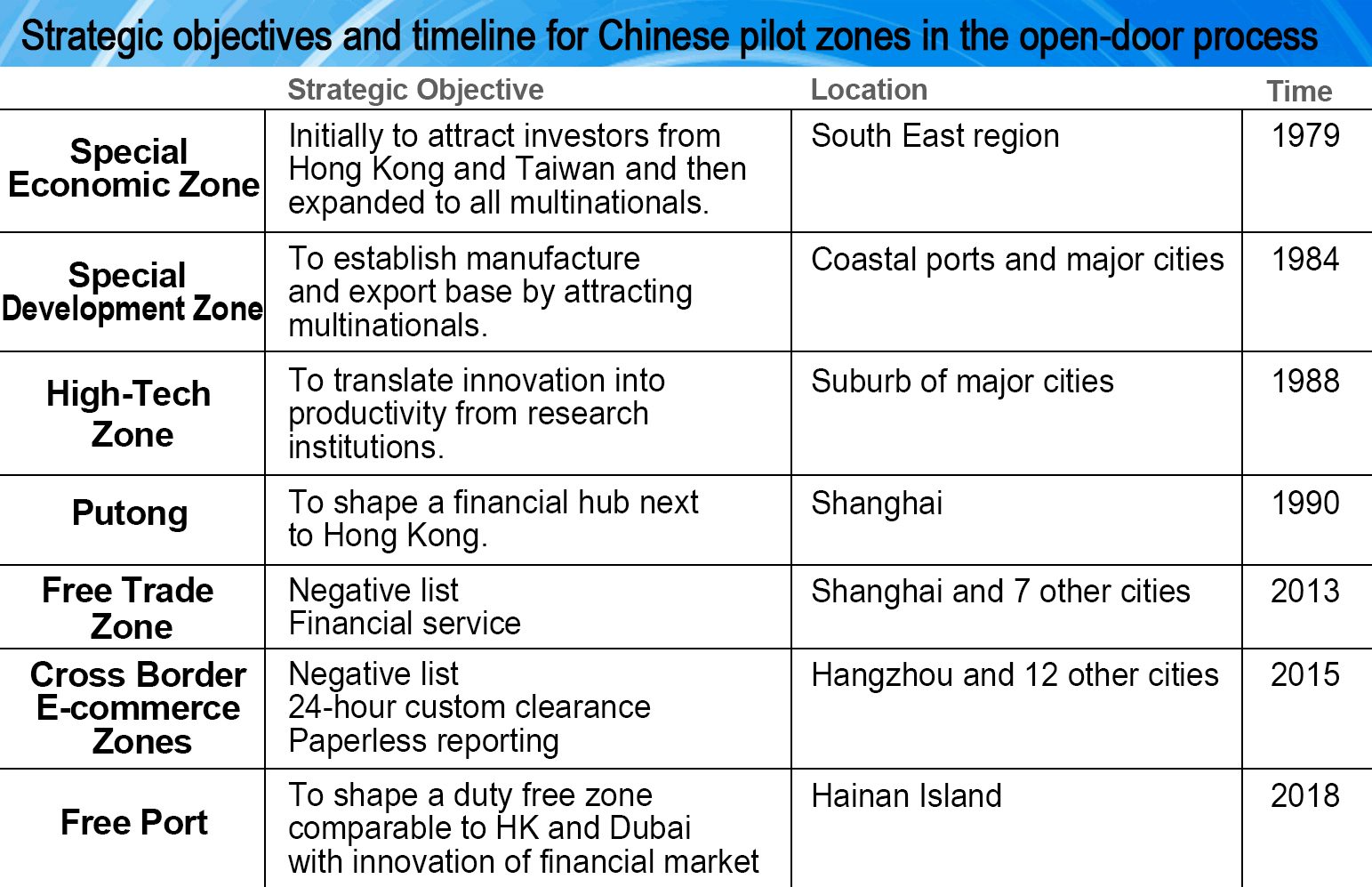

China's opening adopted a gradualist approach through defined lab tests which have endured the test of time with a firm footprint. In July 1979, China decided to open the southeast coast to foreign investment and established the first four special economic zones (SEZs) in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen the following year as a window case to allure business communities across the Taiwan Strait and Hong Kong with incentives such as tax exemptions and land concessions.

This move turned out to be a huge economic success in less than a decade, as those cities flourished on top of Chinese economic growth. With this experience, Hainan Island was added as the fifth SEZ in 1988.

1992 witnessed a renewed impetus of further openness extending inwards first along the Yangtze River and major rail lines and the border regions with neighboring countries.

In the past three decades, hundreds of additional zones have been developed covering an aggregate 550,000km㎡ of land area. In August 1988, China launched the Torch Program aiming at developing high-tech industries.

A number of high-tech zones (HTZs) were set up surrounding big cities intended to take advantage of advanced human capital and innovations from universities and research institutes. In September 2013, China started to integrate the bonded areas into the first free trade zone (FTZ) in Shanghai, implementing a negative list for business operations and opening further for financial services. Ten more in different cities have been added to the list thus far.

In March 2015, the first cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zone was established in Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang province, which hosts Alibaba, to be followed by 12 other cities. In April 2018, China announced the opening of Hainan Island as a free port which rivals Hong Kong, Singapore and Dubai. Apart from duty-free movement of goods, the island province is also a place for financial innovation with exchange centers for commodities, financial derivatives, corporate equity and CO2 Emission.

The establishment of these development zones has not only fueled the Chinese industrialization process aided by the participation of foreign investors with technologies and management expertise but also helped build the largest pool of foreign exchange reserves.

In addition to the lab experiment practice, China's opening has taken a phased approach accompanied by multiple lines, for example, from coastal regions to hinterland areas and from preoccupation with manufacturing to the service sector.

Despite some irregular swings of the policy pendulum in the course of trial and error, the trajectory of the opening-up has been irreversibly leading to a market-driven economy with improved equity and transparency under a globalized context.

Filled with typical pragmatism and common sense, having in practice experienced a stark contrast in living standards between autarky and open-door, few Chinese would accept a reversal of the previous isolation from the world. The opening of the China Development Forum this week reminds us of a solemn pledge in President Xi's address in the Boao Forum last year: China's open door will never be closed; it shall only open wider. He was manifesting the mind of the entire Chinese nation.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3