Editor's note: Ken Moak taught economic theory, public policy and globalization at the university level for 33 years. He co-authored a book titled "China's Economic Rise and Its Global Impact" in 2015. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Canada is perhaps the U.S' closest ally, being the “sons” of a “common mother,” sharing the same language, culture and values. Along with the U.S., UK, New Zealand and Australia, Canada is part of the “Five Eyes” of English-speaking countries, sharing intelligence information with each other.

What's more, the U.S. is Canada's largest trading partner and investor, with over 600 billion U.S. dollars in 2017. Add “kith and kin" to it, the Canada-U.S. relationship is not only “solid as a rock,” but also “special.”

Test of U.S.-Canada relations

Arresting Huawei's chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou on December 1 and holding her until the U.S. sends an extradition order expected in February 2019 is a litmus test of that “solid and special” relationship.

Perhaps aware of the potential damage to the Sino-Canada relationship that the detaining of Ms Meng would cause, Canada went ahead with it anyway, indicating that the U.S. matters more to Canada than China.

That sentiment surfaced in November, based on an Environics Institute poll on how Canadians view the U.S. after Donald Trump captured the presidency. It showed that Canadians have a less positive view of the U.S. because of Trump and his “America First” policy.

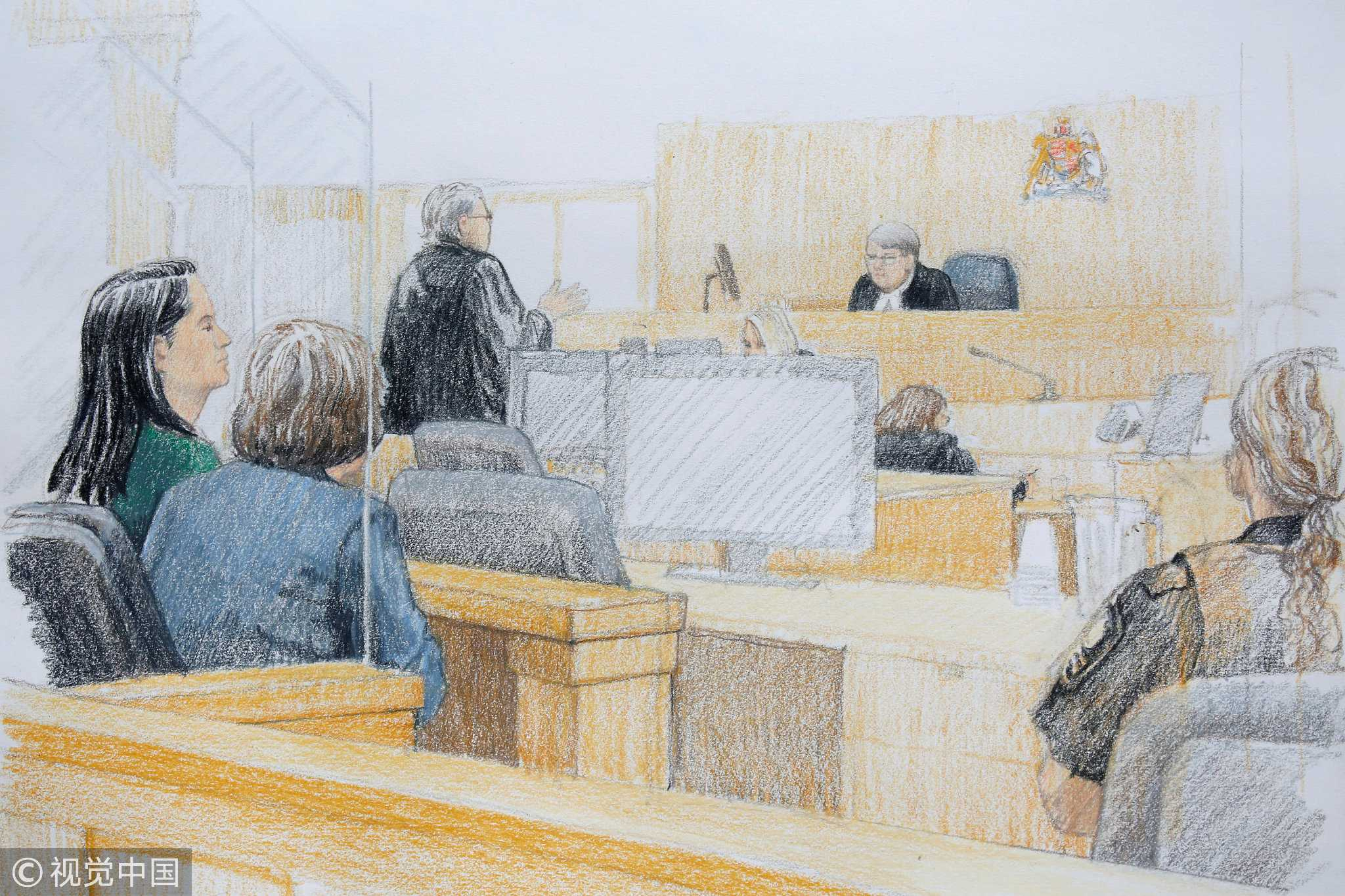

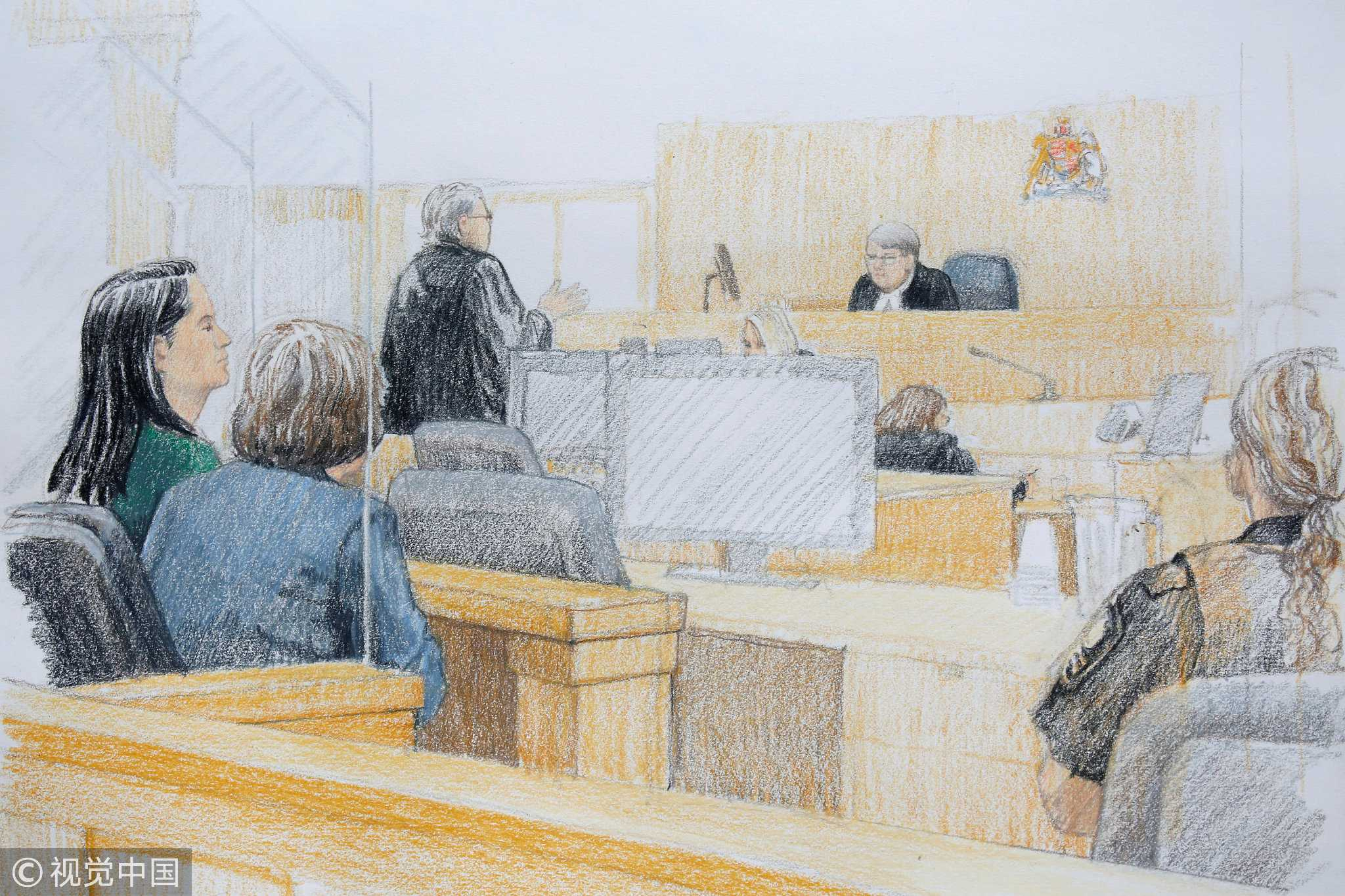

In this courtroom sketch, Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou (L) sits beside a translator during a bail hearing at the British Columbia Supreme Court in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, December 7, 2018. /VCG Photo

In this courtroom sketch, Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou (L) sits beside a translator during a bail hearing at the British Columbia Supreme Court in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, December 7, 2018. /VCG Photo

However, most Canadians still want to do business with their southern neighbor rather than with China even though they feel that a closer economic relationship with the Asian giant would benefit Canada.

Yet, whether the U.S. will come to Canada's aid is less clear.

The U.S. is in the middle of negotiating an agreement to end the trade war. Indeed, both Trump and Pompeo have indicated that the U.S. will only do what is best for America.

That is, Pompeo seems to support a Trump intervention in extraditing Ms Meng to the U.S. if they could get a good deal from China.

U.S.-Canada relations not always “smooth”

The U.S.-Canada relationship has had its “ups and downs” over the years, but largely over economic differences. The U.S. economy, being 10 times the size of Canada's and owning the majority of corporate assets, dominates and influences Canadian economic policies and not always in a good way.

Governor of the Bank of Canada Stephen Poloz listens to Canadian Minister of Finance Bill Morneau during a news conference after the G7 Finance Ministers Summit in Whistler, Canada, June 2, 2018. /VCG Photo

Governor of the Bank of Canada Stephen Poloz listens to Canadian Minister of Finance Bill Morneau during a news conference after the G7 Finance Ministers Summit in Whistler, Canada, June 2, 2018. /VCG Photo

For example, the U.S. embargo on Cuba prevented American subsidiary companies from doing business with the island country, undermining Canadian sovereignty and economic growth.

Former U.S. President Richard Nixon called Pierre Eliot Trudeau, the present Canadian Prime Minister's father, a “son-of-a bitch” over trade issues.

It seems history is repeating itself with a Trump official ridiculing Justin Trudeau as the “little punk kid” running Canada in reference to Trudeau's protest against U.S. tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum as well as the “forced” renegotiation of NAFTA.

On geopolitics, too, Canada did not always agree with its overbearing southern neighbor. For example, former Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien refused to send troops to help George W. Bush invade Iraq, culminating in some U.S. backlash.

It is interesting to note that strained U.S.-Canada relations occurred mostly under a Liberal government. When the Conservatives ascended to power, they reversed Liberal policies vis-à-vis the U.S.

For example, former Canadian Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper sent troops to “train” Iraqi forces shortly after he was elected in 2006.

Is Canada the U.S' “lapdog”?

Calling it a U.S. lapdog would be unfair and an exaggeration, albeit it is true that Canada supports U.S. foreign policies most of the time.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announces the new USMCA trade pact between Canada, the United States, and Mexico in Ottawa, October 1, 2018. /VCG Photo

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announces the new USMCA trade pact between Canada, the United States, and Mexico in Ottawa, October 1, 2018. /VCG Photo

For example, Canada has sent a warship patrolling the South China Sea presumably to help U.S. “freedom of navigations operations,” but it did not follow the U.S. navy in sailing inside of China's 12-nautical-mile territorial waters.

Moreover, Canada did not hesitate to criticize U.S. policies that isolated it. Pierre Trudeau, for example, insisted that the U.S. consults Canada on trade protectionism because the two economies are intrinsically linked.

How “accommodating” Canada is to the U.S. depends on which party is in power. The Conservatives would more likely support U.S. policies even if they are not in Canada's interests.

For example, the Iraq War had nothing to do with Canada, but Stephen Harper reversed Liberal Chretien's policy, sending Canadian troops to help the U.S. “occupation.” Should Andrew Scheer be elected prime minister, he would most likely follow the U.S., Australia and New Zealand in banning Huawei or any other Chinese telecommunications equipment from Canada.

U.S.-Canada relations ahead

From left: Canadian Minister of Defense Harjit Sajjan, Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland, U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo and U.S. secretary of defense James Mattis, at a news conference during a U.S.-Canada 2+2 ministerial meeting in Washington, DC, U.S., December. 14, 2018. /VCG Photo

From left: Canadian Minister of Defense Harjit Sajjan, Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland, U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo and U.S. secretary of defense James Mattis, at a news conference during a U.S.-Canada 2+2 ministerial meeting in Washington, DC, U.S., December. 14, 2018. /VCG Photo

For reasons of “kith and kin,” economic and geopolitical realities, the “solid” U.S.-Canada relationship will likely endure but will have periods of “stress.” It was “frosty” when Nixon was U.S. president, but improved when Mike Pearson and Gerald Ford became leaders of Canada and the U.S. respectively. U.S.-Canada relations were just as good if not better under Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan.

George W. Bush did some damage to the relationship. It was recovered when Obama assumed the U.S. presidency. Trump might have put the relationship on “ice,” but will likely be “warmed” up by his successors.

The U.S.-Canada relationship is one between “brothers,” feuding one day and making up the next day.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)