Opinions

12:25, 28-Nov-2018

Opinion: Why the outcry over gene-editing baby claims?

Updated

11:34, 01-Dec-2018

Zhang Hongbing

Editor's note: Zhang Hongbing is a professor of Physiology at Peking Union Medical College and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

On Monday, a Chinese scientist announced in a YouTube video that he had helped make the world's first genetically-edited babies.

The researcher, He Jiankui, said he had altered a gene in embryos, before having them implanted in the womb of a woman undergoing fertility treatment, with the goal of making the babies resistant to infection with HIV.

He said the pregnancy had been successful and that apparently healthy twin girls Lulu and Nana were born "a few weeks ago."

Though the claim has not yet been verified, the report itself is appalling.

Chinese law prohibits genetic editing of human embryos for medical practice. This experiment lacks transparency and supervision and violated Chinese law and regulation, as well as academic ethics and norms.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) uses CCR5 as co-receptors to enter target cells. CCR5 deficient cells are therefore resistant to HIV infection. This alleged research on embryos is premature, dangerous and irresponsible. It is questionable whether this procedure was necessary or even safe.

The experiment is not medically justified as well. The risks of editing embryos to disable CCR5 seem to outweigh the benefits of resistance to HIV infection. Knocking out CCR5 will likely render a person much more susceptible to the West Nile Virus and other diseases.

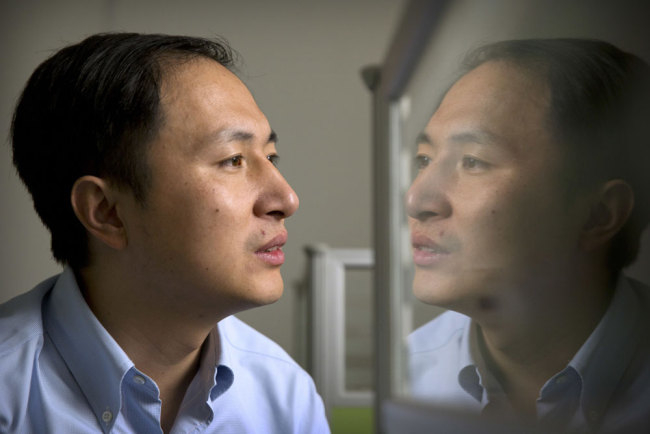

He Jiankui works in a laboratory in Shenzhen, south China's Guangdong Province, October 10, 2018. /AP Photo

He Jiankui works in a laboratory in Shenzhen, south China's Guangdong Province, October 10, 2018. /AP Photo

Furthermore, gene editing is experimental and still associated with off-target mutations. These unknown alterations may cause or make the body vulnerable to diseases sooner or later. Defective CCR5 and potential unintended off-target altered genomes of the twin babies will likely be passed on to future generations.

What makes it worse is that the premature use of gene editing may jeopardize the relationship between science and society, and thus might potentially set the global development of the valuable therapeutics back by years.

Many Chinese researchers expressed concern that this event might damage the reputation of Chinese biomedical research and that it is "extremely unfair" to Chinese scientists who are diligent, innovative and defending the bottom line of scientific ethics.

Indeed, genetic editing of embryos has enormous potential for medical needs. Since this technology can correct genetic defects, it will expand the horizon of in vitro fertilization for couples with genetic diseases.

But genetically modified children should be made only under strict conditions of safety and oversight. Before this procedure comes into clinical practice, we should ensure that manipulation of the genome of human embryos would not cause harm to the future person.

We should set stringent requirements and conduct risk-benefit analysis for the use of genetic editing of human embryos and confine the use of germline gene editing to settings where a clear and serious unmet medical need exists, and where no other medical approach is a viable option.

Current applications in gene editing technology should be restricted to medical intervention but not prevention, i.e., fix the genetic defects but not create defects. The government should set legislation for guidance and punishment for violators.

The two babies should be monitored well. They should avoid exposure to risk factors associated with CCR5 defects and potential off-targeted genes. Genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis and family planning should be provided to them in the future.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3