Politics

13:39, 09-Jan-2019

Brexit debate resumes, but can stalemate be broken?

Updated

13:22, 12-Jan-2019

By John Goodrich

"A week is a long time in politics," former British prime minister Harold Wilson once quipped, so a whole month should surely bring major changes – particularly in a time often described as the UK's biggest crisis since World War II.

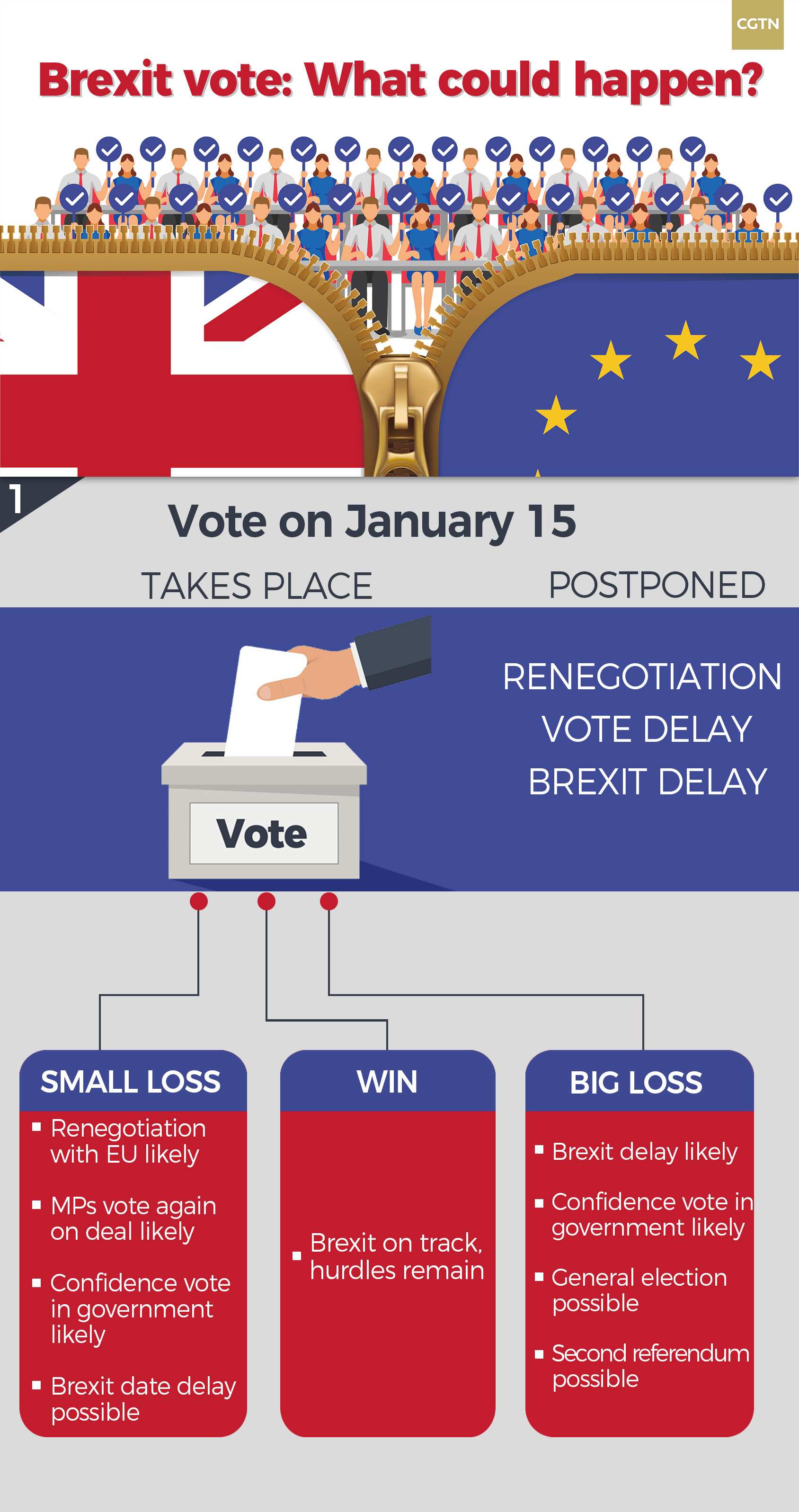

But as MPs restart a debate on Theresa May's Brexit deal on Wednesday, over four weeks after the British prime minister pulled a vote on the agreement, is a smooth exit from the European Union any more likely?

Read more:

Briefings from a Cabinet meeting on Tuesday suggest not, with May conceding that she would probably lose a vote scheduled for January 15 and pledging to "move quickly" in response.

That probably means returning to EU leaders in a bid for concessions, though speculation is growing that a move to delay the Brexit date – currently March 29 – is in the offing.

What's changed?

As the unpopularity of May's deal became clear four weeks ago, her strategy evolved into an attempt to run down the clock, and put pressure on MPs by increasing the risk of a no-deal exit.

Leaving the EU without a deal would have a worse impact on the UK economy than the 2008 financial crisis, according to the Bank of England, and avoiding such a scenario is a rare Brexit issue on which there is a majority in the UK parliament.

The hope was that a majority of MPs would hold their noses and back a deal they don't like rather than risk an outcome they despise.

On Tuesday, a glimmer of hope for the prime minister, who insists there is no alternative agreement to the one she struck with Brussels, emerged from an unlikely source.

A cross-party group of MPs inflicted a government's first defeat on a finance bill in over 40 years as an amendment was passed that would make a no-deal exit more difficult. The alliance, including 20 Conservatives, vowed to continue to work to make a no-deal impossible.

The vote was evidence of a majority of MPs opposing no-deal and could shift the dynamic in parliament. A sizeable number of hardline Brexit supporters favor a no-deal, but fear no-Brexit even more – the government hopes the defeat could ultimately prove to be a winner, persuading hardliners to back May's deal.

However if, as expected, the deal is defeated in the initial vote on January 15, the government is likely to put it to MPs again. May on Sunday repeatedly refused to say she would not bring the vote "again and again and again," though such a move would test parliamentary conventions.

The theory is that a rejected deal would lead to financial turmoil and MPs would back it at the second time of asking to calm the markets, probably with some fresh concessions from the EU thrown in.

New concessions?

May's "run the clock down" strategy was also intended to put pressure on the EU – which would be damaged by a no-deal exit. There is little evidence of the bloc conceding significant ground, though new assurances about the controversial Irish border backstop are expected over the coming days.

Any promises that are not legally binding are unlikely to be trusted by hardline pro-Brexit MPs, however. Tens of May's Conservative MPs continue to oppose her deal for being too soft – notably for retaining the backstop – a position shared by most party members.

A poll by the Economic and Social Research Council in early January indicated that 57 percent of Conservative members would prefer a no-deal Brexit, to just 23 percent who approved of May's deal and 15 percent who wanted to stay in the EU.

British Prime Minister Theresa May at the launch of the NHS Long Term Plan at Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool, January 7, 2019. /VCG Photo

British Prime Minister Theresa May at the launch of the NHS Long Term Plan at Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool, January 7, 2019. /VCG Photo

One significant change since the pulled vote is December's failed attempt to topple May as Conservative leader: It means, even if the prime minister loses the January 15 vote by a large margin, there is no official mechanism for the party to push her out.

Meanwhile the Democratic Unionists, the party the Conservatives depend on for a majority in parliament, at the weekend colorfully reiterated their opposition to the deal in current form, describing the backstop as "the poison which makes any vote for the Withdrawal Agreement so toxic."

And the opposition Labour Party has made no movement, sticking to a position that it will call a no-confidence vote in the government if May's deal is rejected. It too faces a split between leadership and membership: A new YouGov poll suggests 72 percent of members want a second referendum, a move leader Jeremy Corbyn wants to avoid.

So what has changed over the past month? The pressure of time is building, May is a little safer from a party revolt, and a delay to Brexit is slightly more likely.

As Wilson said, a week is a long time in politics: but seven days before the Brexit vote, deadlock remains and a resolution is no closer.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3