Opinion

07:39, 24-Apr-2019

My story: The railroads of tomorrow

Oskar Galeev

03:50

Editor's note: The Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation will be held in Beijing at the end of this month. Over the past six years, we have heard many voices – mostly political and economic – speak about the BRI. But we wanted to also hear from ordinary people who have experienced the BRI for themselves. Over 100 people took part in our "CGTN Belt and Road Essay Contest," and we selected the 18 best stories. Here is an essay of our first-prize winners. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

In the 1990s, when I was a kid, my parents frequently moved between Moscow and Saint Petersburg, the two largest cities in Russia, and my native city of Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan. With family relatives scattered among these three cities, I would take a train with my mom every couple of months and spend each season in a new place.

Moscow-Kazan High-Speed Railway Project. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

Moscow-Kazan High-Speed Railway Project. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

Such a train ride between Kazan and Moscow – roughly the same distance as between Xi'an and Chongqing – would normally take up to 14 hours. Many of my childhood and adolescent memories are connected to the experience of riding those Soviet-made trains and to how my family would calculate our plans in accordance with train schedules.

Today, the Moscow-Kazan high-speed rail is among the main Belt and Road projects in Russia, one part of a much more ambitious plan to build a high-speed link between Moscow and Beijing. The railroad promises to do much more than cutting the travel time between Moscow and my hometown in Tatarstan to only three hours. If successful, this project could boost the quantity of passenger connections in a number of cities in Russia and in the Russian-speaking countries of Central Asia, transforming the region in the same way that the high-speed boom has transformed China.

Views of Kazan from the railroad. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

Views of Kazan from the railroad. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

Within just one decade after the launch of the first Chinese high-speed train, China has built more high-speed rail tracks than the rest of the world combined. Anyone who has lived or traveled in China in the past few years can appreciate this massive change and how it has reshaped the whole experience of moving around in the country.

The new land connections of the Belt and Road have already started to fill in a significant infrastructure deficit common to many countries of the former Soviet Union. In Uzbekistan, the Angren–Pap railway line was finished in 2016, linking the Fergana Valley, the most densely populated area in Central Asia, to the rest of the country. Similar projects are being developed to construct a China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway and a trans-Kazakhstan line from the fast growing Khorgos dry port in the east to the port of Aktau in the west.

The historical center of Kazan. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

The historical center of Kazan. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

Often posing engineering challenges, the new railroads of the Belt and Road reshape local landscapes and cut right through mountains. This is the case with the Angren–Pap railway, the construction of which includes the longest railway tunnel in all of the ex-USSR. As a result, connections that were previously considered impossible have become a reality, and distances that took days to cross can be completed in no more than a few hours.

Tatarstan, lying at the heart of Russia's Belt and Road connections, will undergo drastic changes with this fresh potential. And because the coverage that the Belt and Road projects receive is often focused on the big picture and their political implications, we often forget about how they affect people's everyday lives. Be it a weekend trip to visit your parents or just travelling to a nearby city for work, new transport connections profoundly transform our lifestyles. They allow us to travel to places we would otherwise never see and help us to meet different sorts of people.

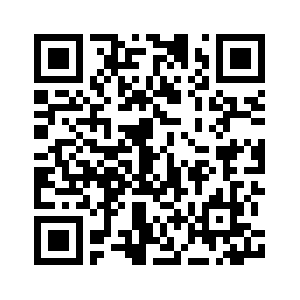

Oskar Galeev and his family at Kazan Railway Station in 1998. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

Oskar Galeev and his family at Kazan Railway Station in 1998. /Courtesy of Oskar Galeev

This wider resonating change is one of the reasons why the Belt and Road is not at all only about economics and politics. It is going to have a long-lasting impact on the societies and cultures of the participating countries. For me, it means I can see my grandmother more often, and for someone else it could mean finding a new job opportunity. But for everyone, the Belt and Road has the potential to bring people closer and make the world more connected than ever before.

(The author is a Russian student at Yenching Academy of Peking University. If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3