Domestic

19:52, 29-Mar-2019

No longer a tiger mom: Shifts in Chinese parenting style

By Wang Yan and Yu Jing

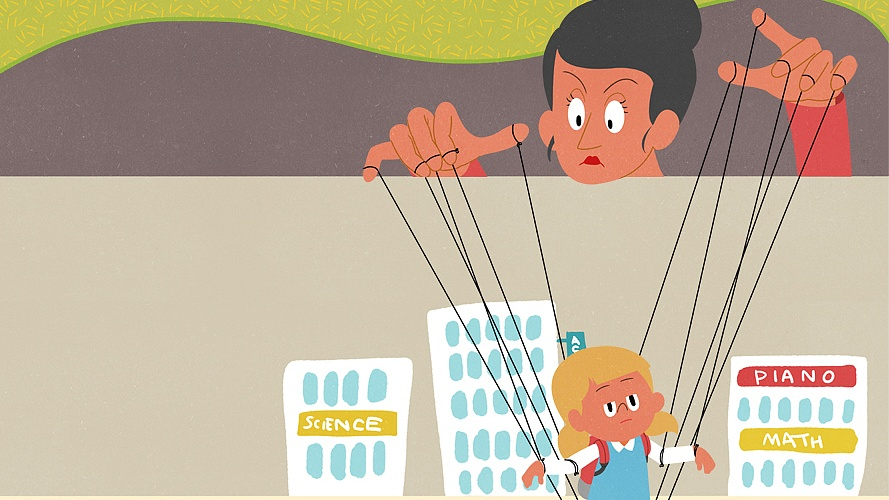

For decades, the perception towards Chinese parents is that of tiger parenting—strict parents with tightened control on children, a keen resolve for better academic performance at school even at the expense of everything else.

Increasingly, a different style of parenting has come into force as a younger, more cosmopolitan generation of Chinese parents has taken center stage. No longer obsessed with making their children "dragons and phoenixes" of the society, they are in search of a more well-rounded education where independence of the mind and a willingness to contribute to social good are highly valued.

Experience-oriented rather than result-oriented approach

Ms. Yu, 51, whose son already landed a job on Wall Street after graduating from a college in the U.S., is now preparing to send her second child, a daughter this time, to an American college.

Since elementary school, her daughter has been attending bilingual schools, speaks English with an impeccable American accent and has taken up hobbies like cello, oil painting and tennis.

A graduation ceremony at an international school. /VCG Photo

A graduation ceremony at an international school. /VCG Photo

Every year, apart from the regular tuition fee of the international school, which is around 18,000 yuan (2,670 U.S. dollars) per month, Ms. Yu's family throws another 80,000 to 100,000 yuan (11,915–14,894 U.S. dollars) toward her daughter's extracurricular activities, one-third of which goes to supporting her hobbies, the rest goes to her English debating classes. From time to time, her daughter attends debating tournaments around the nation as part of the class, and Ms. Yu covers her registration and accommodation fees.

Won Chian Lim, founder and debate coach at SpeechCraft, a Shanghai-based communications training firm, who has tutored Ms. Yu's daughter over three years, said that from his observation, Chinese parents these days invest heavily in helping their children attain happiness, and the emphasis on success is not as heavy as in the past.

This shift in mentality is reflected in the growing popularity of courses like debate, camping and study tours, where the relation to academic performance may not be as direct as cram schools for Chinese or math.

"Parents these days do not want to have control over the test results; to let their kids experience as much as possible is the key," Won noted.

Children participate in outdoor activities at a camp. /VCG Photo

Children participate in outdoor activities at a camp. /VCG Photo

Marco Reyes, co-founder of You Mei Camp Education Group, also notices the trend. At his camps, kids group together to participate in outdoor activities like Boy Scouts, where soft skills like communication and leadership are bestowed. At the traditional American camps that he organizes, with their cellphones taken away, kids are required to spend one week together with eight other kids in a camp and communication becomes integral.

"Parents start to feel that schools, academics and scores are not going to be everything. They need to have more well-rounded kids...I definitely see a merging between the American style of parenting and Chinese style," Reyes noted.

A rising new middle class

Behind the freedom to experience life, taking on courses that do not offer immediate returns is the growing economic largess of the new generation of Chinese parents.

According to Hurun's 2018 China New Middle Class report, around 33 million families in China can be counted as "new middle class" – people who after spending money on basic expense still have 50 percent of their income left. Though the industries they work in vary, what connects them all is their emphasis on their children's education.

Won noted that most families who send their children to attend debate classes at his school have an annual investment of around 150,000 yuan (2,227 U.S. dollars) to 200,000 (2,970 U.S. dollars) on education. Many of the parents hold managerial positions at family-run business, private firms or multinational companies and thus understand qualities like effective communication and critical thinking are relevant and important in employment situations.

Pan Ying, a 43-year-old mom whose daughter goes to the elite international school Harrow Beijing, says one incentive for sending her daughter to unconventional extracurricular activities like debating and camping is to let her daughter enjoy the life that was not available for her in China decades ago.

Students attend a debating competition. /VCG Photo

Students attend a debating competition. /VCG Photo

Coming from a small village in a rural area, Pan was the first one in her family to earn a college degree and now with her husband being on the executive board of a private company, her daughter went to ski in Switzerland at the age of 8 and has had private English tutoring class with an American teacher for three years.

"I think for those families, no matter how traditional they were, how local-minded they were…they want their kids to have everything and opportunity at their hand. A lot of it is because they did not have those opportunities when they were younger," said Reyes. Though parents who send children to his camps do not all fit in the criteria of "new middle-class," the willingness to offer their kids the best they can is universal.

Is education still necessary for social mobility?

China's gaokao system, no matter how grueling it can be, still offers those from remote provinces a gateway to social mobility. But a "well-rounded" education that comes with debating practices, skiing or camping may be out of reach for those from remote areas.

Asked if he is concerned that his courses contribute to growing class division in China, Won said though his class caters to today's new middle class, it is ultimately going to serve the mass market in the future, whether from a business sense or an educational perspective.

Students attend lectures at a cram school in China during the night. /VCG Photo

Students attend lectures at a cram school in China during the night. /VCG Photo

"In Singapore, debate education is part of the English curriculum – an integral part of English education," said Won, "In the U.S., critical thinking is also part and parcel of the SAT test." As more people become aware of the importance of such skills, schools are likely to react and try to integrate them into the curriculum.

With growing demand comes diversification in the market. Reyes noted that compared with when he first started, parents these days are more cost-conscious. Since there are camp programs charging 1,500 yuan per week, the traditional 60,000 yuan per week camp is no longer the go-to option.

Rather than solely catering to students at international schools or students in the international division at public schools, his camp has been partnering with local public schools, on areas where schools are not doing so well, including building soft skills, learning how to build up with people.

"We are diversifying for sure. That means the price will diversify, and the market will diversify…It shouldn't be just for elites," he said.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3