Opinions

09:03, 11-Jan-2019

Opinion: Time to empower China's agricultural sector with artificial intelligence

Updated

08:56, 14-Jan-2019

Ni Tao

Editor's note: Ni Tao is a Shanghai-based journalist and opinion editor. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

China's Ministry of Education issued an action plan in early January, imploring universities nationwide to take part in a drive to revive the countryside through innovation. The document outlines seven ways in which college researchers can help: capacity-building, nurturing talent and hastening the application of lab results, among others.

A highlight of the plan is that it encourages colleges to apply artificial intelligence (AI) to improve the efficiency in agricultural production.

As an important enabling technology meant to effect radical changes across a wide spectrum of industries, AI seems at this point grossly under-represented in China's agro-economy.

Farmers are harvesting carrots in Baoying County, east China's Jiangsu Province, January 9, 2019. /VCG Photo

Farmers are harvesting carrots in Baoying County, east China's Jiangsu Province, January 9, 2019. /VCG Photo

Part of the reason has to do with the fact that China's agricultural sector is disparate. Regions vary wildly in terms of their levels of automation. Coastal areas may be geared for a data-driven approach to overhauling traditional farming methods, but some inland provinces, where plots continue to be tilled by hand, are nowhere near the point of entering the fast lane to digitized agriculture.

And their position at the shallow end of a talent pool hardly predisposes them to embrace AI or any other fancy tech buzzwords. This is changing due to several trends.

The first is a demographic shift. Aging and dwindling rural workforce, with an average age of 55 according to a 2016 census, means that the rural sector will soon be struggling to fill jobs deserted by young people who migrate to towns.

As the concentration of arable land deepens, industrialized farming calls for mainstreaming technologies once considered “ahead of their time.”

Moreover, environmental pollution has been a lightning rod for criticism, compelling farmers and government officials alike to look for innovative ways to restrict the use of pesticide and fertilizer – the two culprits behind soil decay and contaminated food.

All of this has provided fertile ground for experiments with AI, which is widely credited for tapping the hidden value of data.

Examples from advanced Western economies show us why it pays to adopt AI in agriculture. In Florida, for instance, shorthanded farmers rely on robots to pick strawberries. Robotics is proven to be a reliable helper in this type of work, operating with the precision necessary to keep the fruit intact.

Waxberry farmers in China can perhaps envision a similar scenario with these robots. Waxberry has a short lifespan. Every year in Yuyao, eastern Zhejiang Province, where waxberry is a local specialty, hundreds of tons of the ripened fruit go unharvested and are left to rot during the plum rain spell in summer, amounting to tens of thousands of yuan in lost income.

Harvest robotics is one of the most obvious use cases for AI in farming, but more sophisticated applications will have to involve computer vision, machine learning and algorithms compiled to study the correlation between data.

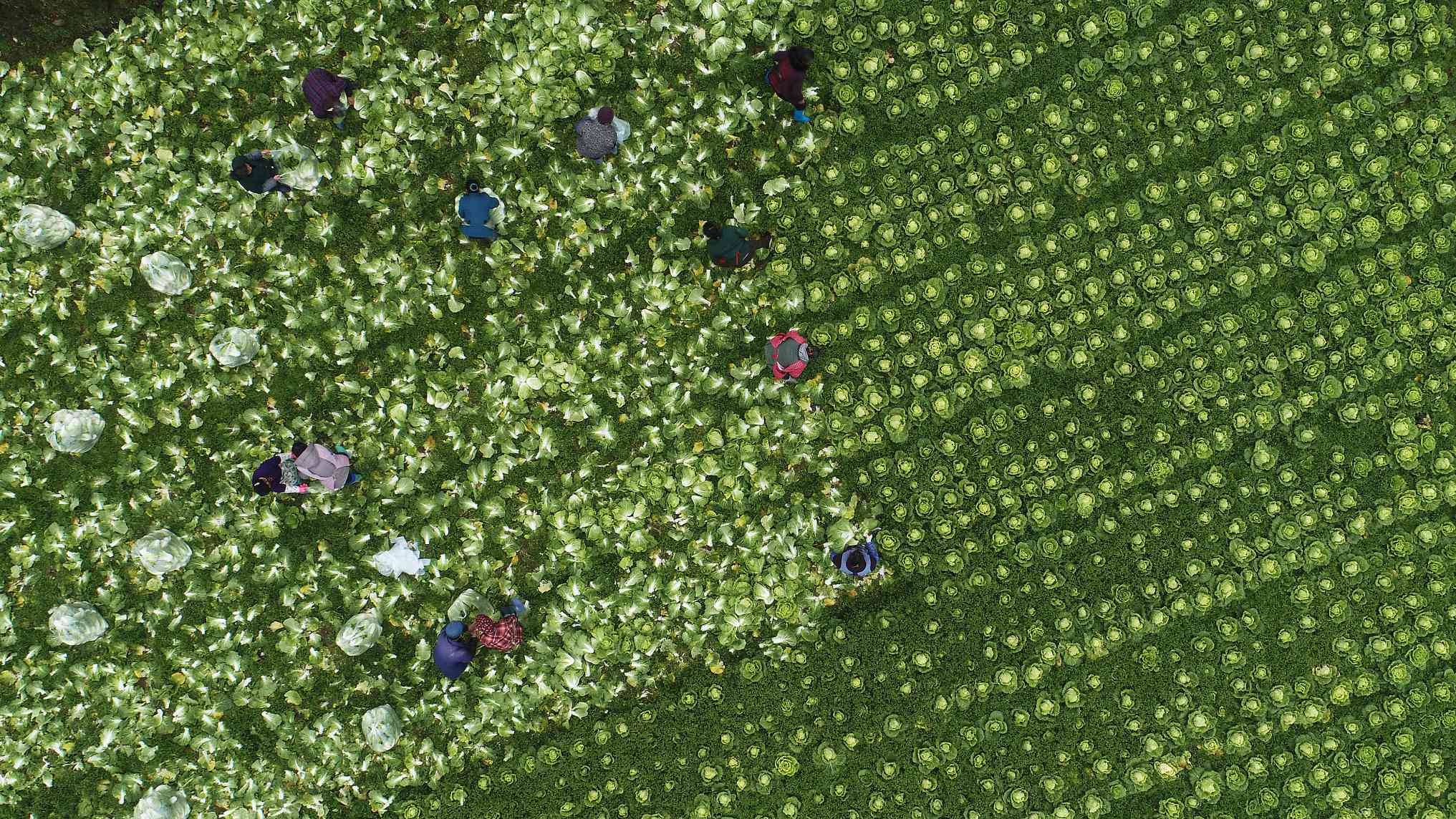

Farmers are harvesting in Longli County, China's southwestern Guizhou Province, January 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

Farmers are harvesting in Longli County, China's southwestern Guizhou Province, January 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

A top priority for ranch owners in the U.S. is to weed their fields with less herbicide. Spraying entire fields is polluting and wasteful. A robot called See & Spray developed by the U.S. company Blue River Technology has come to their aid. It analyzes computer-generated images to determine which spots of the fields are most teeming with weed, and in need of an intense spray.

The effects are immediate. Precision spray cut chemical residues on plants by 80 percent and reduced the spending on herbicide by 90 percent.

Take another example. PEAT, a Berlin-based startup company, is now the best friend of retail farmers without access to expert opinion on pest or weed control. Instead, they use Plantix, an app by PEAT, to take a photo of their crops, beam it over to a server, and cross-reference it against a database of a variety of crop species using image recognition.

Within a few minutes, an AI-powered analysis report arrives on farmers' smartphones, informing them if their crops need more water, or if they need to cut back on the use of fertilizer to produce more in line with organic standards and thus more sought after by health-conscious customers. Plantix reportedly boasts a registered user base of 500,000 across the globe.

For many AI firms, a transition toward the agricultural sector may also be a much-needed shot in the arm for themselves.

The commercial drone market is a telling illustration. The market is so saturated that many companies have been forced out of business. A few are tempted by a move into agriculture to avoid head-on competition with DJI, a Shenzhen-based manufacturer and market leader.

Drones spraying pesticides have become a familiar sight by now, many equipped with high-performance cameras and modules that are capable of much more. They take photos of crops and transmit data to a cloud server to be analyzed. On the next mission, drones will be able to load less pesticide and aim more accurately, “knowing” which plants to target.

Tencent Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Pony Ma attends the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai, China, September 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

Tencent Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Pony Ma attends the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai, China, September 17, 2018. /VCG Photo

The involvement of AI proves essential to meeting China's goal of zero growth in pesticide use by 2020. At present, the country, with 10 percent of the arable land on earth, consumes 35 percent of the world's pesticide and fertilizer. Early movers like Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent have been using AI to change the face of agriculture. Alibaba, for one, employs voice recognition in diagnosing diseases like cold in pigs raised on smart farms.

AI, however, is not exclusive to big tech, nor should it be. More and more Chinese startups are actively seeking to apply their expertise and know-how to do farming, rather than waste resources in a crowded market rife with cut-throat competition. At the college level, we anticipate more rewards, grants or favorable policies from the Ministry of Education to incentivize the gravitation of technology toward agriculture.

For a long time, agriculture carries a stigma in China. The perception that it is a "backward" industry has prompted many to shy away from employment in farming. But AI promises to change that by brightening the career prospects for college graduates drawn to agriculture and by making farming a respectable and trendy profession again.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3