Asia Pacific

16:30, 22-May-2019

Fake news rampant after Sri Lanka attacks despite social media ban

CGTN

Sri Lankan social networks saw a surge in fake news after the Easter suicide bombings a month ago despite an official social media blackout.

A nine-day ban on platforms including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram and WhatsApp was introduced following the Islamic State-claimed attacks on churches and hotels on April 21 which killed 258 people and wounded nearly 500.

Many anxious social media users switched to virtual private networks (VPNs) or the TOR network to bypass the order and keep communication open with friends and relatives as the extent of the carnage became clear.

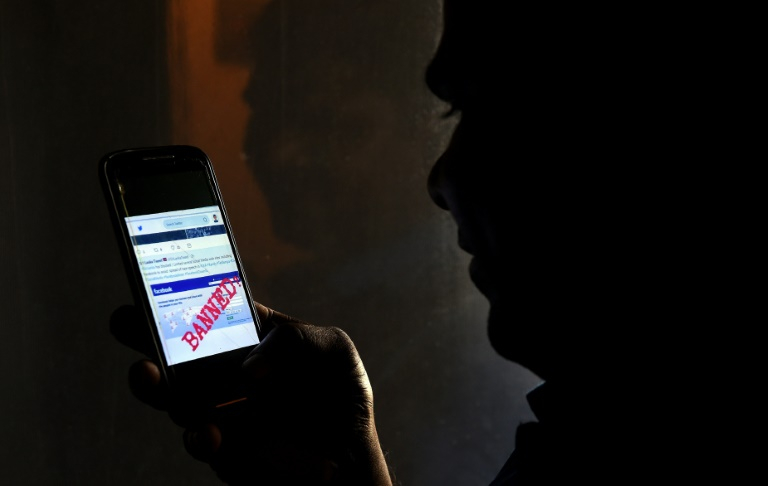

Authorities in Sri Lanka have banned Facebook in the past in a bid to prevent hardliners from using social media to ignite violence. /AFP Photo

Authorities in Sri Lanka have banned Facebook in the past in a bid to prevent hardliners from using social media to ignite violence. /AFP Photo

But for others, the tools were a means to spread confusion and vitriol as the island struggled to come to terms with one of the worst terror attacks in its history.

Sanjana Hattotuwa, who monitors social media for fake news at the Centre for Policy Alternatives in Colombo, said the government blackout had failed to prevent "engagement, production, sharing and discussion of Facebook content", and that he had seen a significant increase in false reports.

False claims on Facebook

AFP has published half a dozen fact-checks debunking false claims made on Facebook and Twitter after the Easter attacks.

People attend the funeral of Dhami Brindya, 13, a victim of the Easter attack, Negombo, Sri Lanka, April 25, 2019. /VCG Photo

People attend the funeral of Dhami Brindya, 13, a victim of the Easter attack, Negombo, Sri Lanka, April 25, 2019. /VCG Photo

Some had dug out photos of coffins and funerals from Sri Lanka's brutal decades-long civil war and claimed they showed victims of the blasts.

One video posted to Facebook showed police arresting a man dressed in a burqa and claimed he was involved in the bombings. The video was actually from 2018, and showed a man who had used a burqa to hide his identity while he sought to attack someone over a debt issue.

Another used a five-year-old photo from India that showed a group of men wearing T-shirts with "ISIS", another name for Islamic State group, written on them to claim there was an active ISIL cell in eastern Sri Lanka.

Soldiers search a motorist at a checkpoint on a street in Colombo, Sri Lanka, April 25, 2019. /VCG Photo

Soldiers search a motorist at a checkpoint on a street in Colombo, Sri Lanka, April 25, 2019. /VCG Photo

One Twitter user claiming to be a high-ranking Sri Lankan army brigadier used the platform to accuse neighboring India of being involved in the attacks. The account was later taken down by Twitter after the Sri Lankan army complained.

Since the attacks, Sri Lankan authorities have imposed other short bans on social media, including earlier this month after mobs in the northwestern town of Chilaw attacked Muslim-owned businesses in anger at a Facebook post by a shopkeeper.

(With inputs from AFP)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3