Flavor

11:35, 05-Feb-2019

Melaka’s hybrid culture creates tasty treats

Updated

14:47, 05-Feb-2019

By Rian Maelzer

02:17

Lying just outside Melaka's UNESCO heritage zone, Tengkera or Tranquerah is still steeped in history. Its 300-year-old mosque resembles a pagoda, with its heavily Chinese-influenced architecture, though it was the Dutch colonists who commissioned its construction.

The district used to be home to the Eurasian or Serani community, people born of the intermarriage of Portuguese colonists and locals.

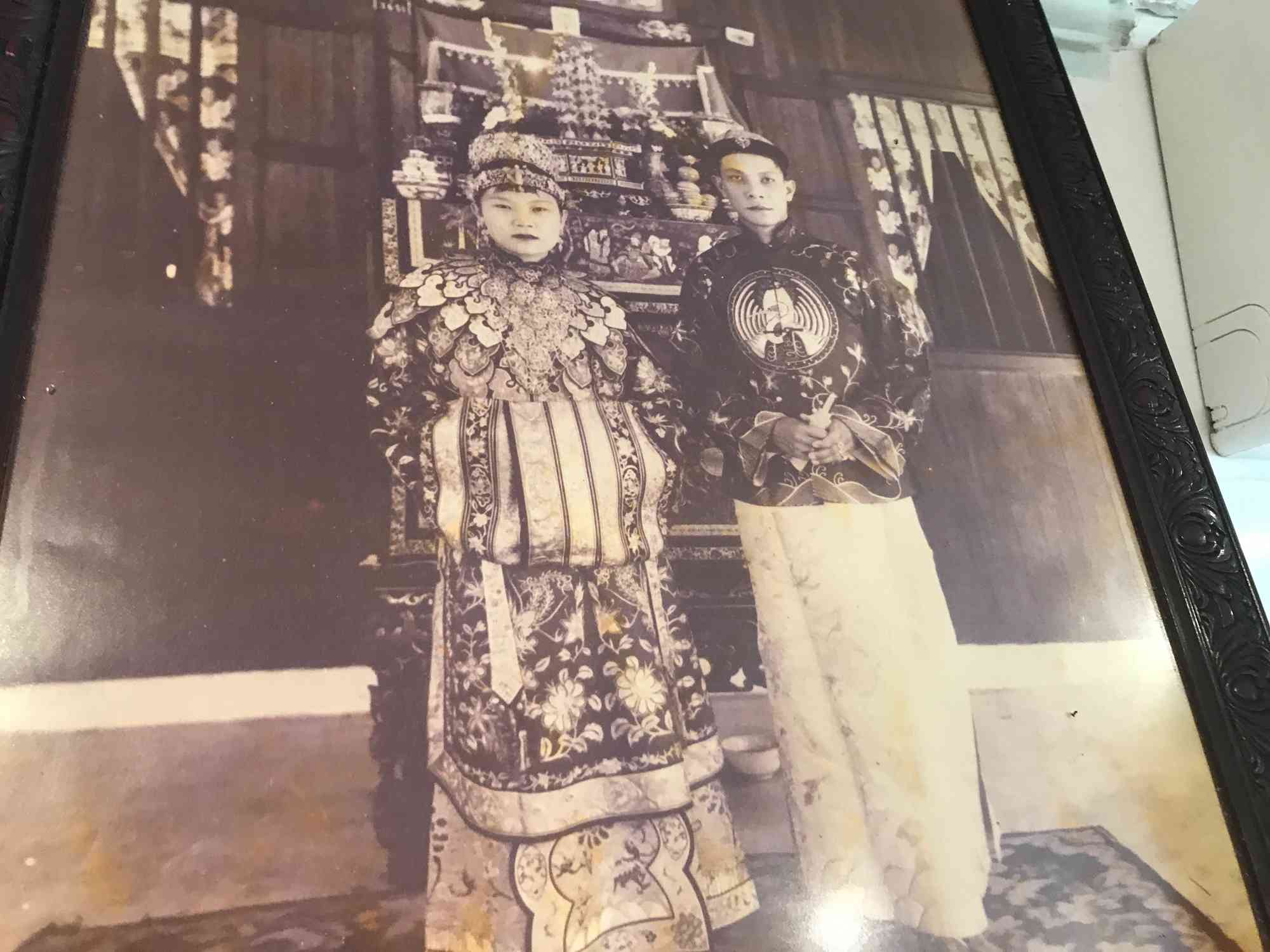

Baba Charlie's parents were married in traditional Baba Nyonya style. /CGTN Photo

Baba Charlie's parents were married in traditional Baba Nyonya style. /CGTN Photo

And it is also home to Baba Nyonya, a group descended from Chinese who settled in the Malay Peninsula centuries ago and married local women, and who have played a central role in the history of Melaka. Baba is the term for men, Nyonya for women.

This hybrid mixture of Chinese and local cultures and traditions can be seen in their architecture, clothing and marriage ceremonies, heard in their now-nearly extinct dialect, and tasted in their cuisine.

People of all races and nationalities seek out the kuih. /CGTN Photo

People of all races and nationalities seek out the kuih. /CGTN Photo

Down a nondescript side street across from the Tengkera mosque, a stream of people flows in and out of an entranceway. A sign reveals this to be the home of Baba Charlie's kuih shop. Kuih is the Malay word for snacks or cakes, though the word is in turn derived from the Chinese Hokkien dialect.

Baba Charlie Lee is one of the city's most famous makers of Nyonya kuih. While shoppers browse the shop at the back, in the kitchen portion, women kneed and roll and boil and steam a kaleidoscopic variety of kuih in hues of green, blue, pink and yellow.

Leaves and flowers are used for kuih coloring. /CGTN Photo

Leaves and flowers are used for kuih coloring. /CGTN Photo

They are flavored with ingredients that will be familiar to people in Southeast Asia, but much less so in China: pandan leaves providing its distinctive taste and green color, butterfly pea flowers giving some kuih their bright blue hue, the golden brown paste of gula Melaka or palm sugar, shredded coconut and coconut milk, tapioca, sago, and black glutinous rice.

Kuih is made with ingredients such as pandan leaves, palm sugar, tapioca, coconut and sago. /CGTN Photo

Kuih is made with ingredients such as pandan leaves, palm sugar, tapioca, coconut and sago. /CGTN Photo

Baba Charlie's mother used to make kuih to send to the local schools when he was a kid.

"I learned from my mum. I liked to watch what she was doing. And she would tell me 'You want to help me? Ok', so I learned how to make the kuih. (The skill was passed down from) my grandmother's generation, to my mother then to me. Many years, I think about 70 years."

The recipes have been passed down for three generations. /CGTN Photo

The recipes have been passed down for three generations. /CGTN Photo

Charlie's mother still helps out in the kitchen, with the team starting to make the kuih well before dawn. It is best eaten within hours, and a flood of people not only from Melaka but also other parts of Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and elsewhere eagerly snap up the treats, especially at this time of year.

"Due to Chinese New Year I came over to buy the kuih," one woman told me. "I buy it every year at this time. The taste is excellent." Another couple was there buying the kuih to treat some out-of-town visitors to an authentic Melakan Baba Nyonya delicacy.

Gula Melaka or palm sugar is a key ingredient in many kuih. /CGTN Photo

Gula Melaka or palm sugar is a key ingredient in many kuih. /CGTN Photo

A group of students from Kuala Lumpur researching the Baba Nyonya culture were also visiting, watching the preparations and snapping up some kuih while they are at it.

"People buy the kuih for parties, gatherings, marriages, open houses," says Baba Charlie… and just to enjoy with their morning or afternoon tea.

Students from a Kuala Lumpur university come to shop as part of their research on Baba Nyonya culture. /CGTN Photo

Students from a Kuala Lumpur university come to shop as part of their research on Baba Nyonya culture. /CGTN Photo

I, of course, had to sample some of the kuih. They are noticeably less sweet than the Malay variety, which suits my tastes. One small green ball containing pandan leaves and rolled in shredded coconut releases a burst of liquid palm sugar into my mouth as I bite into it. Another layered kuih topped by a smooth coconut cream paste follows.

"Once you take the kuih you must have some Chinese tea," says Charlie, and I duly follow his advice.

The blue coloring comes from the butterfly pea flower. /CGTN Photo

The blue coloring comes from the butterfly pea flower. /CGTN Photo

The dialect of the Baba Nyonyas – a creole of Malay sprinkled with plenty of Hokkien words – is dying out in Melaka, and you won't see women wearing the Nyonya kebaya or dress or beaded shoes except on festive occasions. But Nyonya cuisine – both savory and sweet – is still very much alive.

And judging by the enthusiastic crowd thronging Baba Charlie's kuih shop, demand for Nyonya cakes and snacks will keep this tradition alive for generations to come.

(Cover: CGTN's Rian Maelzer (L) tries out Baba Charlie's kuih. /CGTN Photo)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3