Hopes that the Brexit deadlock in Britain's parliament would finally be broken this week have been dashed.

Facing a huge defeat, British Prime Minister Theresa May on Monday announced that she would

delay a vote on the Brexit deal she struck with the European Union after 20 months of negotiations in hopes of drawing additional "assurances" from Brussels.

There are many criticisms of May's deal, but the primary objection is the "backstop" arrangement, designed to ensure there is no hard border between northern and southern Ireland. It is essentially a shared customs area and would only come into force if no UK-EU trade deal was agreed by December 2020. But many MPs fear it would create a separate status for Northern Ireland and argue that given a mutual agreement would be needed to end it, the UK could be held hostage in negotiations with Brussels.

May, who conceded she would have lost a parliamentary vote by a "significant margin," now aims to persuade European leaders at a summit on Thursday and Friday to offer concessions on the contentious "backstop" before putting the deal before the House of Commons.

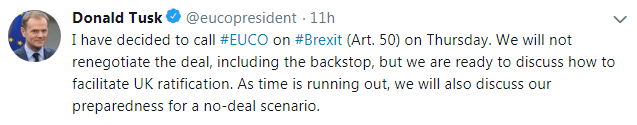

The EU response of "we will not renegotiate the deal" – and May's own speech to parliament on Monday suggested any changes would be cosmetic, so using the pressure of time and financial markets in panic looks to be her strategy to push through the deal.

By postponing the landmark decision, which had been scheduled for Tuesday evening, the time between the new vote and the current exit date of March 29, 2019 has been cut – and with it the country's options.

The pound dropped to a two-year low following May's statement to parliament, and there is a majority of MPs against a "no deal" exit – which most experts warn would be catastrophic for the UK economy.

May said on Monday that preparations for an exit without a deal would be stepped up, with just 16 weeks until Brexit day. Faced with the clock ticking towards a chaotic exit, she is hoping for moderate MPs to swing behind her deal.

However, there is little evidence that this will happen.

On Monday, many voiced frustration that the deadlock-breaking vote – won or lost – had been delayed. And the government was castigated by John Bercow, the speaker, for its handling of the process.

No date has been set for a new vote, with the only hard deadline being January 21 – when the government has to reveal its plans in the event of no deal being reached.

Britain's Prime Minister Theresa May makes a statement in the House of Commons in London, December 10, 2018. /VCG Photo

Britain's Prime Minister Theresa May makes a statement in the House of Commons in London, December 10, 2018. /VCG Photo

The delay maintains deadlock in parliament, where there are majorities against various options, but no majorities in the affirmative, while lessening the likelihood of an attempt to topple May in the short term.

The hardline Brexit group within the Conservative Party which tried and failed to force a vote of confidence in May's leadership in November is supportive of a managed "no deal" exit, so a delayed vote could play into their hands. The risk for them, which May has already tried to play on, is that support for a second referendum is growing.

The opposition Labour Party, meanwhile, said it would not call for a vote of no confidence in the prime minister despite calls from other opposition parties to do so. It is expected the government would narrowly win such a vote at present.

The delay shores up the prime minister for now, and she could still spring a surprise election, attempt to push back the Brexit date, revoke Article 50, or call for a second referendum. But using an impending "no deal" as leverage to try to force through her agreement is a high-stakes strategy.